Darwin Day is February 12th, and for an early celebration I thought I’d take a look at a book that rethinks the way Darwin, and we, think about evolution—a very specific part of evolution, the way beautiful features and behavior have developed amongst birds and, by extension, amongst humans. You may have already read The Evolution of Beauty: How Darwin’s Forgotten Theory of Mate Choice Shapes the Animal World – and Us by Richard O. Prum, or at the very least heard about it The book was published last spring (the paperback version is due out in spring 2018), and articles based on book chapters were been published in The New York Times, National Geographic, and Natural History. It made the ‘best book of the year’ lists of several publications, including my own Top Five on the ABA podcast, and Prum has been doing the lecture circuit, including talks at NYC Linnaean and the 92nd Street Y.

Basically, Prum takes issue with the “adaptionist” interpretation of Darwin’s writings, which focuses almost purely on On the Origin of Species and the famous maxim, ‘survival of the fittest.’ Form develops according to function and sexual mating choices are based on choosing the mate best configured to deal with the environment. Even traits like the long, gaudy feathers of the peacock, the elaborate dances of the manakin, and the ornate architectural creations of the bowerbird have adaptive value–indicating good genes and survivalist abilities.

Prum counters with the theory of aesthetic evolution, articulated in Darwin’s second book, The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex. Darwin theorized that sexual selection was an important element of evolution and consisted of two parts: (1) competition within one species for control of the other species (as in male competition), and (2) sexual selection, usually by the female, and, furthermore, that females chose males based on aesthetic criteria—their own standards of beauty. The first part was embraced, and the second part—a very dangerous idea, Prum says–was ignored. He says the danger lies in its challenge to the concept of “survival of the fittest” as the primary engine of evolution. But, reading this in the time of the “Me Too” movement, I tend to think that the ‘danger’ lies in giving scientific credibility to the transformative power of the female, whether she be bird, mammal, or human.

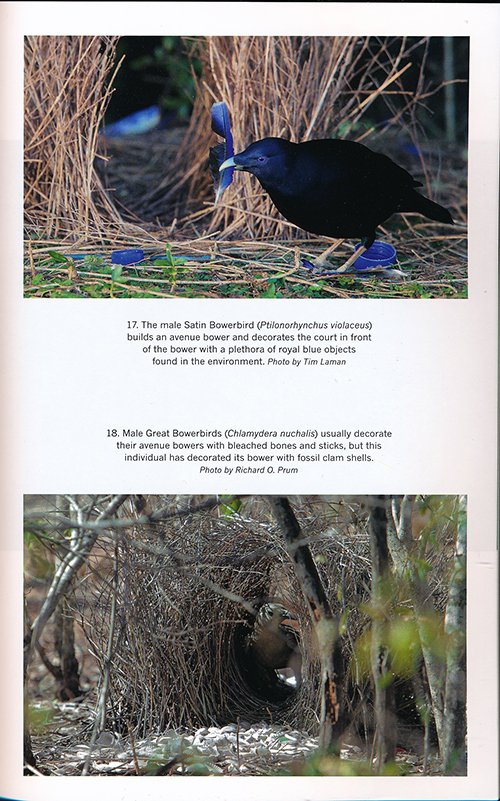

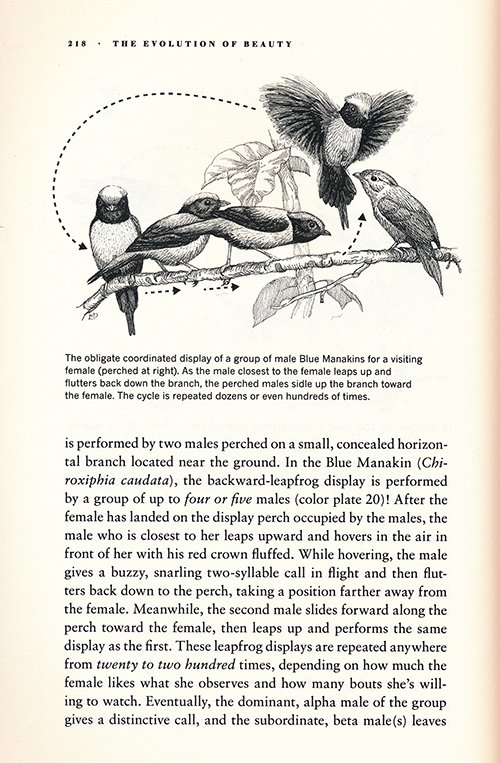

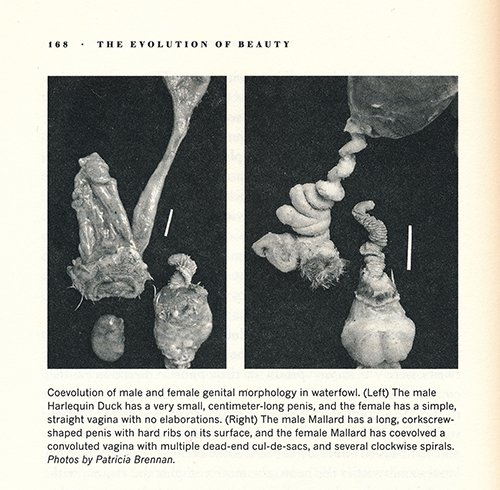

Richard O. Prum has had a long, productive, award-studded ornithological career, a chaired professor of ornithology at Yale and recipient of a prized MacArthur fellowship. He has researched and published on Manakin behavior, the evolutionary development of feathers, phylogenetic reconstruction, evolution of genitalia in living birds, the physics of structural coloration in birds, and the dinosaur origin of birds. He uses all of this knowledge, as well as the work of ornithologists he has mentored such as Kimberly Bostwick and Patricia Brennan, to support, explain, and explore the concept of female sexual selection and the evolution of beauty as it is played out by birds in the first two-thirds of the book. Chapters focus on the feathers of the Great Argus; the diverse dance displays of Manakin species (clearly the bird closest to Prum’s heart and this chapter is informed by his personal experiences observing and studying them); the Club-winged Manakin, whose male members sing with twists and snaps of their wings; and the twisted sex organs and violent sex lives of ducks; the incredibly varied decorative creations of Bowerbirds (my personal favorite).

I would have been very happy simply reading about these birds and the research projects that uncovered their unique behavior, biology, and evolutionary history. Who can resist Manakins, and though we don’t get a video of the Red-capped Manakin (and Kimberly Bostwick) dancing to Michael Jackson, we do get a personal history of how Prum discovered and mapped out the complex flight displays of the White-throated Manakin (with the help, my NYC birding friends will be interested to know, of Tom Davis, now gone but of legendary birder reputation), plus diagrams of how a coterie of Blue Manakins team together to dance a display for a single female (above).

Or, the fascinating yet distressing tale of discovering how duck sex actually works, with the long, corkscrew-shaped penis of certain male ducks and the complexly structured vagina of the female of the species, the two involved in an evolutionary arms race involving rape and the blocking of rape attempts (this is the only ornithological books I’ve read that quotes Susan Brownmiller). Prum proudly describes the unique methods undertaken by his colleague, Patricia Brennan, which included the construction of glass duck vaginas.

These tales are told within the larger framework of proving that “beauty happens,” that aesthetic sex selection is a ruling evolutionary principle, and so the engaging narratives of research adventures are interspersed with Prum’s use of the research findings to prove his point. In a voice that is friendly but unceasingly adamant, Prum presents questions, reasons out answers, finds holes in these answers, and then reasons things out some more. There were times when I found these sections difficult to follow. I think using lay language rather than more specific scientific terminology often results in over-lengthy, convoluted explanations, here and elsewhere, and that the narrative approach of Prum ‘talking’ to the non-scientific reader ended up reading more like a Ted talk than a cogent piece of writing (Prum has indeed done a Ted talk, using many of the photographs featured in this book).

In the last third of The Evolution of Beauty, Prum makes an enthusiastic effort to apply his ideas–Beauty Happens, sexual conflict, aesthetic remodeling– to humans. Utilizing a mixed bag of human and primate sex studies, literature, myth, and the Old Testament, Prum muses on the evolution of the penis, the female orgasm, male-female sexual conflict and same-sex relationships. Much of this, as Prum himself admits, is speculative and it is far less compelling than the ornithological chapters. His observations and conclusions (“sexual desire and attraction are not just tools of subjugation but individual and collective instruments of social empowerment that can contribute to the expansion of sexual autonomy…”; “the cultural evolution of patriarchy has prevented modern women from fully consolidating the previous evolutionary gains in sexual autonomy”) are familiar to anyone who has studied feminist theory.

The Evolution of Beauty devotes considerable end-of-the-book real estate to Notes, an extensive Bibliiography, and Index. The Bibliography is the traditional mix of monographs and journal articles, and I think could have been expanded with links to online depictions of some of the avian behavior described in such detail, such as the Red-capped Manakin video I linked to above. Videos, like the illustrations and diagrams included in the book, help make literature about science, especially theoretical science, more accessible to us non-scientists.

If you haven’t read The Evolution of Beauty, I suggest you dip into it. You may not be totally convinced by Prum’s arguments for Darwin’s theory of aesthetic evolution, and by Prum’s expansion of that theory into the mechanisms of sexual conflict and aesthetic remodeling, but you will learn a lot about unique, magical birds, and duck sex and the brilliant ornithological research that continues to seek insights into matters of beauty and evolution.

The Evolution of Beauty: How Darwin’s Forgotten Theory of Mate Choice Shapes the Animal World – and Us

By Richard O. Prum

Doubleday, 2017, 448p. Hardcover; $30; paperback due out April 2018, $17; ebook and audiobook versions available (book discounts available from the usual suspects)

ISBN-10: 0385537212; ISBN-13: 978-0385537216

Leave a Comment