Bird blogging in May always gives me the creeps. This ridiculous focus of the Birding Internet on North American wood-warblers is boring on a quiet day and highly annoying during peak migration. Birders in the Americas may not be aware of it, but from the higher ground of a European perspective the American “warblers” are intensely overrated. To us on the traditional side of the Atlantic, they’ll always belong to the family Iznogoudae, the birds who want to become warblers instead of the warblers. And do they ever try so hard. Imagine, they think they can beat the original by applying colours to their plumage. Who enjoys seeing that?! Not me, that’s for certain. I therefore decided to counter this month’s heinous wood-warbler attack on my retina by choosing the good old trusty House Sparrow as the topic of my May post. The House Sparrow exemplifies all we love about birds and birding:

- It is insanely attractive as it exhibits a cunning combination of browns and greys, reminding us of a beautiful bark pattern.

- It is reasonably to very common and fun to watch, living in highly entertaining social flocks.

- It visits bird feeders, making it a worthy spark bird to new birders as they may see it closely.

- They never asked to be released in areas outside their natural distribution and have no means of asking us to take them back to where they belong. Therefore, they cannot personally be held responsible for anything they do there to the native flora and fauna.

- In its natural old-world range, the House Sparrow offers an interesting identification challenge and has vagrant potential since it is a polytypic species with a highly complex taxonomy.

The last aspect is something I will elaborate on further below, but not before showing off a prime fine male House Sparrow, unethically photographed at its nest site.

The genus Passer has several well-recognized and recognizable species in Europe, and still holds several enigmas. I’ll start off by naming the univerally accepted species, the House Sparrow propper Passer domesticus, the Eurasian Tree Sparrow Passer montanus and the ill-named Spanish Sparrow Passer hispaniolensis, which occurs from Spain all the way to central Asia and is rather difficult to find in the former. As we move from Spain towards the east however, it starts getting interesting as soon as we reach Italy. Italy has an almost endemic … well … “form” of Sparrow, the Italian Sparrow, whose taxonomic affinities and rank have been a matter of dispute ever since scientists started to think about it. You see, it clearly resembles a hybrid between the Spanish and the House Sparrow, and an ancient hybrid event was long suspected to be the source of its existence – with recent research indicating that apparently this isn’t the case after all. It therefore comes as no surprise that it has been regarded as a subspecies of the Spanish Sparrow or the House Sparrow, or as a species in its own right. Not too long ago, the British were convinced that it belonged to the House Sparrow while German taxonomy placed it under the Spanish Sparrow. This resulted in difficulties with the German version of the famed “Collin’s Bird Guide” as from a German perspective a subspecies of the Spanish Sparrow was depicted amongst the different plumages of the House Sparrow. Crazy stuff.

A fine male Italian Sparrow at the overwhelmingly expensive cafe of Florence’s Uffizi. The entirely brown cap and white cheeks are elements of Spanish Sparrow while the rest is basically House Sparrow.

We currently are experiencing a rare time where all major taxonomic bodies tend to regard it as a species in its own right, the Italian Sparrow Passer italiae. This doesn’t necessarily reflect a scientific clarification of the matter – rather it is the most practical thing to do. Well, they could have simply placed it within the Asian babblers, but sadly that taxonomic swamp has recently been drained and scientists can’t just dump uncertain species there anymore.

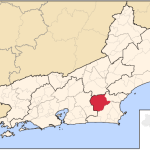

Anyway, this current taxonomic classification has interesting implications to German birders. The Italian Sparrow is not entirely confined to Italy but – not surprisingly – also occurs in neighbouring areas of Austria and Switzerland. There are currently no German records of the species, in spite of it occurring in Austria less than 35 km south of the German border. And while this may be the genuine result of limited dispersal, an intrepid German birder longing for a national first record could do worse than scanning flocks of sparrows at Alpine mountain passes which form the border to our southern neighbours.

Now, leaving Italy and moving further towards the east, we reach a very interesting part of the good old House Sparrow’s range. The House Sparrow is a highly variable species, and no less than 12 subspecies are currently recognized. These subspecies can be divided into two major clades, the domesticus group and the indicus group, with the indicus group occupying south and parts of central Asia. Members of the indicus group have often been regarded as a separate species in the past, and some taxonomists still tread them as such today. The males can be distinguished from domesticus House Sparrows by a more extensive black throat and upper breast and almost entirely white cheeks, while the females of most forms tend to be much paler than domesticus females.

A male probable member of the indicus group (foreground) and a male domesticus House Sparrow in western Kazakhstan. Winter plumage makes things a bit more difficult, but the difference is rather obvious.

I’ve had the good fortune of seeing indicus House Sparrows in central Asia quite frequently and I must admit that I would not be surprised if more thorough taxonomic research would eventually show them to be a separate species. While the differences are restricted to just a few features, they give the birds such a distinct appearance that we (a group of three seasoned birders from Germany on a trip to Kyrgyzstan in the late 1990s) failed to identify our first indicus as a House Sparrow. We were absolutely certain that we were looking at an entirely different species and were desperate because we couldn’t find a matching image in our field guide. Then there is the fact that indicus sparrows tend to avoid human habitations while domesticus doesn’t, leading to sympatric breeding with a disputed amount of hybridisation. However, most interesting of all is the fact that indicus birds from central Asia are long-distance migrants that winter in south Asia, while the domesticus birds breeding in the same general area remain on their breeding grounds year-round. First of all, this really does not sound like something subspecies occurring in the same area should do. And secondly, this means that indicus has a significant vagrant potential and may actually turn up somewhere west of its usual range. Which would be an incredibly interesting thing to document as there are – to the best of my knowledge – no records of indicus from anywhere within Europe.

So, next time you venture out in May to search your North American neck of the woods for warblers and are disgrunted at finding only House Sparrows, take a minute to reflect on how exciting the species really is in its propper home.

I. Am. Legend.

.

Not one of my faves but I respect them. Like you wrote, “They never asked to be released in areas outside their natural distribution…” They’re just trying to make a living like everything else. After reading “Providence of a Sparrow: Lessons from a Life Gone to the Birds,” it’s hard to hate. After reading the article “The More Feathers a Male Sparrow Carries to the Nest, the More Eggs the Female Will Lay” I learned that the male works hard to keep his lady happy. Who can hate on a guy who just wants to make the lady of the nest happy?!? Not I!