Author Sherrida Woodley thinks deeply about dearly departed birds. She’s contemplated California Condors here before, but Passenger Pigeons seem to resonate most with her. The extinct American pigeon plays a pivotal role in her award-winning bio-thriller, Quick Fall of Light and occupies Sherri still, as you can see…

Every now and then I let myself fantasize about the wildest thought of all—about Passenger Pigeons. That one or two or a few might still exist somewhere “incognito,” perhaps in the company of doves or rock pigeons, maybe even somewhere deep within the Olympic Rain Forest of Washington State. Imagining birds is not hard for me to do, especially ones hard to distinguish from their little-noticed cousins lingering around train tracks and grain silos, park benches, and the high perch of church steeples. When a species as prolific as the passenger pigeon once was ultimately expires, and promptly so on March 24, 1900, I’m apt to consider the rare but exceptional future sighting as a possibility, simply because I like to believe birds, or other creatures for that matter, don’t necessarily die within our specific time frames. I recently found some testimonies giving me reason to believe I might not be too far out of bounds.

The last confirmed sighting of a wild passenger pigeon was in 1900, when a young boy in Pike County, Ohio, shot it. That’s definitely a confirmed witness. However, there were other sightings over the years following, some of them giving rise to much speculation, and probably in their day, a few jeering remarks. Naturalist C.F. Hodge, of Worchester, Massachusetts, claimed in the fall of 1905 he was working in his garden when he looked up “and saw a flock of about thirty wild pigeons winging their way southward.” Feeling he was destined to prove to the ornithological world that the passengers were not yet extinct, he named committees and offered rewards for anyone who could substantiate his claim. But after almost a decade of anticipation, no one confirmed his enthusiastic belief.

Dr. W.T. Hornaday, once director of the New York Zoological Garden, wrote that a naturalist in a county of northern Pennsylvania claimed to have fed a flock of 300 pigeons during the autumn of about 1903. Another nature lover of central Pennsylvania, John H. Chatham, saw a lone male passenger in the woods of his estate in approximately that same year. He claims to have watched the bird for about twenty minutes. And one of the most interesting witnesses of that era was naturalist and writer, John Burroughs, who was quoted in Birds of New York, published in about 1906, that he’d personally seen “large flocks of passenger pigeons in the Catskill Mountains in the first few years of the twentieth century.”

But two people, both of them very astute, especially in matters of nature, were very insistent they’d seen passenger pigeons long after their declared extinction in the wild. Theodore Roosevelt, both bird watcher and then President of the United States, said that in May 1907, when staying at the family’s cabin in Albemarle County, Virginia, he saw “what he believed to be a small flock of passenger pigeons, the first he’d seen in 25 years.” Wisely, he obtained corroboration from a neighbor.

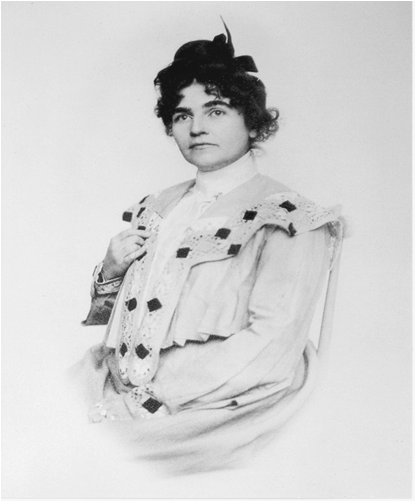

And lastly, novelist, naturalist, and photographer, Gene Stratton-Porter claimed she witnessed the visit of a lone male sometime in 1912 when she was in the field studying other birds. Evidence notwithstanding, she was not credited with the sighting due to the earlier declaration of extinction, but she so strongly maintained she’d witnessed the close proximity of a male passenger that she wrote an essay called “The Last Passenger Pigeon” in which she described her experience. The work stands as a tribute to something already long vanished, a ghost of her Indiana childhood.

Gene Stratton-Porter (Photo used with the permissions of the Indiana State Museum and Historic Sites)

Gene Stratton-Porter (Photo used with the permissions of the Indiana State Museum and Historic Sites)

As for me, I didn’t see a passenger pigeon until visiting the World Center for Birds of Prey in Boise, Idaho, about three summers ago, a specimen tagged and strangely out of place in a haven for raptors. So touched by the experience that I cried, I’ve only seen one since, his body preserved in some formal likeness of what he once had been. I miss what I will never see, if only because I’ve spent so much time as a novelist envisioning passengers in flight and holding their own in a world dead-set on eliminating them one more time.

I cannot say whether I believe every sighting listed above. But I do know that birds, perhaps beyond all other creatures, mystify us by their disappearance and then return. Many of them do it every year in the form of migration. Some of them simply vanish, then tempt us with their possible existence (think Ivory-Billed Woodpecker). The passenger pigeon, wild pigeon as it was sometimes called, was just that. Wild and free, my guess is the bird died out originally in vast numbers, but hung on in small groups until the woods slowly emptied through various forms of suppression. The passenger pigeon lived on in the collective memory of regret for many years after its extinction. There’s reason to believe, a few, maybe just a very few, reinforced the memory by their rare and haunting appearance.

Online Sources:

Tri-Counties Genealogy & History by Joyce M. Tice (July 2001). Transcription of previously published book, The Passenger Pigeon in Pennsylvania, Its Remarkable History, Habits and Extinction, with Interesting Side Lights on the Folk and Forest Lore of the Alleghenian Region of the old Keystone State by John C. French. Specifically Chapter XXVII, “The Passenger Pigeon, Its Last Phase” by Henry W. Shoemaker—Retrieved September 12, 2013, from: http://www.joycetice.com/books/1919pp27.htm

Theodore Roosevelt Center, Dickinson State University (August 2013/GrantCarlson). “Blog-Passenger Pigeons”—Retrieved September 12, 2013, from: http://www.theodorerooseveltcenter.org/Blog/2013/August/09-Passenger-Pigeons.aspx

Tales You Won’t Believe (1925) by Gene Stratton-Porter. “The Last Passenger Pigeon,” pgs. 211-230.

Perhaps, just perhaps, a few renegade flocks managed to survive:

http://www.horiconbirds.com/sightings.html