When we started organising Parrot Month we wondered (a little anxiously) how it would be recieved by our fellow bloggers: month-long, organised themes might not be seen as blogworthy. Turns out we needn’t have worried. We’ve been truly inspired by the generosity of some top-class bird bloggers who’ve handed reams of text and some world-class photos over to us for posting. Case in point is this lip-smacking report on the Military Macaws which visit the small Mexican town of Jaumave by well-known tour leader and general all-round great bird guy Jeff Gordon…

The Military Macaws of Jaumave, Mexico

Text and photos copyright Jeffrey A Gordon (http://jeffreyagordon.com).

I make my living in large part leading birding trips. So what do I do when I get a chance to have some free time with family and friends? I go birding, of course! Last November, just prior to working at the Rio Grande Valley Birding Festival, my wife, Liz, and I blocked out a couple of days and headed for Northeast Mexico with a couple of friends for one of those crazy, long-weekend natural history blitzes. I’d like to share with you what for me was the peak experience of the whole trip, indeed one of my favorite moments of all of 2008–a visit to the small town of Jaumave.

About 200 miles south by southwest of Brownsville,Texas, just a cactus spine south of the Tropic of Cancer, tiny Jaumave lies on the western, semiarid side of the El Cielo Biosphere Reserve. El Cielo’s 144,530 hectares surround much of the rugged, northeastern flank of the Sierra Madre Oriental.The reserve is home to spectacular wildlife including Jaguar, Ornate Hawk-Eagle, and Great Curassow. It supports wild populations of no less than seven parrots and parakeet species, an impressive number considering its rather northerly location. (Here’s a post I did recently on the Red-crowned Parrot Amazona viridigenalis, which is endemic to northeast Mexico.) An eighth species, the Vulnerable Maroon-fronted Parrot, occupies pine-oak forests to the west of the reserve proper.

We reached Jaumave early on the morning of November 4th, 2008. It looks pleasant enough, but unremarkable–what would lure a birder down from the mountainous wilds of El Cielo to this place? If you read Spanish, you already know–this archway reads, “Welcome to Jaumave. Sanctuary of the Macaw.” Now, if you were to hear tell of something that billed itself as a macaw sanctuary, your mind might flash to an image like the one below–a forlorn Military Macaw imprisoned in a chain link cage. Too often, this is exactly what one encounters at lodges, restaurants and various other “eco-” attractions.

But if there are any caged macaws in Jaumave, we didn’t see them. We turned off the highway, parked, and immediately began listening and watching. The streets were full of the noises of a small town awakening to its daily routine, the usual domestic cacophony. Why would macaws, universal symbols of vanishing neotropical wilderness, visit here? You might be able to spot the answer in the photo below:

It’s in the trees, specifically, the kind of tree that fills the sky between Jim and Liz above. Pecans, or Nueces, in Spanish. Each winter, from about November until January, the pecan trees of Jaumave put out an energy-rich treat that turns the entire town into a giant macaw feeder.

We had to wait only only a few seconds before the air was torn by a loud, guttural, “RRRRRAAAAWWWWKKK!” Macaws! And not far away–we jumped back in the car and hurried over to where we thought the sound was originating.

There, not 50 meters away, was a spectacle I’d only dreamt of: whole trees nearly groaning under the weight of several dozen Military Macaws. I’d seen the species before, more than a few times, but always they were distant or in flight. Usually, they were both. We carefully maneuvered ourselves around to get them in better light, but they were relatively unconcerned, ignoring the comings and goings of schoolchildren and workers headed to their occupations.

There was an audible rain of pecan bits and pieces as this nut-cracking battalion made their way through the canopy. Their untidy feeding style proved a boon for an army of White-winged Doves that swooped in below each macaw-filled tree, scavenging their cast offs.

Periodically, the macaws would launch into flight, rowing their way to another tree. This, for me was the most thrilling part of all. These birds are big and impressive perched, but flying right over your head, they are stupefyingly huge.

It was also in flight that their colors were most spectacular–there’s an iridescent quality to their wing and tail feathers that has to be seen to be fully appreciated. It’s different than the strobe light intensity of hummingbirds or sunbirds–it comes and goes more slowly, with an almost wave-like cadence. Take a look at the blues and reds in flight feathers of the bird below as it comes in for a landing.

Though these macaws weren’t shy, they weren’t like park pigeons, either. They kept fairly well on the move. If we focused to much attention on one, it would usually clamber away, moving higher and or deeper into the foliage. But their movements may have been as much to do with hunger as anything. As the morning wore on, they seemed more settled, changing trees less often.

They also seemed to spend more time interacting with each other. Liz captured a short video of a pair engaged in what certainly appears to be courtship and at least pre-copulatory, if not full copulatory, behavior.

After having only known these birds as fleeting apparitions in inaccessible places, it was thrilling to have such a luxurious window into a bit of their domestic lives. Yet I’m kind of glad they’re not in Jaumave everyday. It’s nice that they still spend most of their year in the wilderness. But what an incredible thing to have them make their annual pilgrimage here. Can you imagine how cool it would be to have these red and green monsters come to your town each year, just in time for the holidays?

Eventually, the sun got harsher and our stomachs began to protest that breakfast hour was long past.We reluctantly left the macaws and walked into the town square, or zocalo, where it was our extreme good fortune to run across Milton De la Garza, who, seeing our binoculars and cameras, enquired if we had seen the macaws.We assured him that we had and that they were our primary reason for visiting, but that we were impressed with the overall friendliness of the town.We asked if he could recommend a restaurant and he unhesitatingly answered, “Janambres.”

Turns out that Milton actually works in the local tourism office and he joined us at Janambres, where we chatted about Jamauve and its attractions. That’s Milton above, seated in front of a mural depicting an indigenous man holding–what else?–a Military Macaw.

We were served by the lovely and vivacious Teresa Medina Montoya, who whipped up a brunch for us that was everything we could have hoped for–even cooking the red sauce for our eggs from scratch as we watched. It was heavenly.

Travel has its share of frustrations. Flat tires, bad food, inclement weather, needless bureaucratic and other delays–the list goes on and on. And that’s before you even get out to the birds and other great stuff you came to see, which may or may not cooperate. Sitting over our coffee and chilaquiles, talking with Milton and Teresa, and reviewing our photos and memories of the macaws, I was struck that we were having a perfect ecotourism experience. There was nothing about our visit to Jaumave that I would have changed.

As has been chronicled in these pages of late, conservation frequently involves heroic struggles. Too often we only decide to try to protect a species once we have nearly extinguished it. Our morning with the macaws was a reminder that it doesn’t always have to be that way. Sometimes, all that is necessary is making a little room for nature.

The people of Jaumave could easily have eaten, caged, sold, or otherwise destroyed these birds. Instead, they chose to open their homes to both the macaws and to us. Here’s to them all–thanks for showing us a better way for parrots and people to coexist.

Additional information from BirdLife International (at http://www.birdlife.org/datazone):

Current population estimate: 10,000-19,999, trend Decreasing.

This species is listed as Vulnerable because levels of habitat loss and capture for the cagebird trade indicate that there is a continuing rapid population decline. Its future ought to be secured by the large number of national parks in which it occurs, but many of these currently provide ineffective protection.

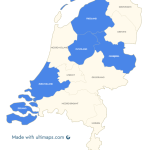

Range & population: Ara militaris occupies a massive but fragmented range from Mexico to Argentina. In Mexico, it occurs from central Sonora to Guerrero on the Pacific slope and east Nuevo León to San Luis Potosí on the Atlantic slope. In Colombia, it is known from the Guajira Peninsula and Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta through the Sierras de Perijá and de San Lucas, south along the East Andes, with local populations on the Pacific slope in Chocó, the Cauca valley, the head of the Magdalena valley and in the Sierra de la Macarena. It is very local in north Venezuela, and occurs disjunctly in the east Andes of Ecuador, Peru (also in the río Chinchipe drainage1), Bolivia and north-west Argentina. It has been extirpated from many areas, especially in Mexico (practically extirpated from most of Veracruz and Hidalgo on the Atlantic side, and Chiapas, Oaxaca, as well as coastal regions of Guerrero and Michoacan on the Pacific slope) and Argentina. Populations in Mexico, Venezuela and Colombia face continuing threats, and further extirpations are expected.

Ecology: It inhabits humid lowland forest and adjacent cleared areas, wooded foothills and canyons. In Mexico, it is found in arid and semi-arid woodland, and pine-oak, humid lowland and riparian forest, moving seasonally to dense thorn-forest, although in Puno, Peru it was found to be more abundant in a mosaic of shade coffee plantations and degraded remnant forest patches than in neighbouring pristine Yungas forest. It occurs from sea-level to 3,100 m, but the core range is 500-1,500 m. Nests and large communal roosts are sited on cliff-faces or in large trees.

Threats: Habitat loss and especially domestic trade are the chief threats, even within reserves. In 1991-1995, 96 wild-caught specimens were found in international trade, with Bolivia and Mexico possibly the most significant exporters. In many areas it nests in relatively inaccessible cavities on cliff walls, which provides some protection against the pressures of nest poaching. However, nest poaching is a severe threat in Jalisco and Nayarit where the species nests in tree cavities. In Jalisco, Mexico, macaws were not found in deforested areas, even where abundant Hura polyandra (an important food source) were left as shade for cattle. GARP analysis estimates that the species has suffered 23% habitat loss within its range in Mexico.

Amazing as always, Jeff! I’m so sorry I missed this experience.

Awesome post!

Was just sent your blog. I love it. I just got a Military Macaw from a friend of mine and she is beautiful. I found your blog very enjoyable reading and the pictures are magnificent! Look forward to seeing more of them…Joanne

What wonderful photos! Great way to enjoy birds in the wild (at least vicariously). Really enjoyed seeing the video. Thanks so much. Sandy S.

Terrific post, like being there. Incredible coloring in this bird. I had not noticed the turquoise before. And as always, important notations about attitudes and how to help our declining species.

jaumave is beatiful my dad is from jaumave tamaulipas. I have to many vacations in jaumave Im live in Nc.

Thank you, Jeff, for these incredibly beautiful photographs and interesting information. There is so much emphasis on the blue macaws and the red macaws in the wild: few seem to appreciate how stunning are Military and Great Green Macaws. I think this will change the minds of many people.

I know about Jaumave,becouse I was born in Tamaulipas, but I didnt know about the military Macaws…this is amazing Jeff, thanks for show ourselves to mexicans the natural richness we have….

Dear Jeff: A good friend of mine Dr. Alexander N.G.Kirschel, Marie Curie Research Fellow, Edward Grey Institute, Department of Zoology, Oxford University, suggested to me to get in touch with you. I am Colombian and not a bird watcher expert. I just like birds in general and mainly macaws. I just came back from the Las Piedras and Tambopata rivers in Peru, and was amazed with these birds. I will be traveling to Mexico next february to see the monarch buterflies in Michoacan and would like to take advantage going some place quite near??? the DF that is not Chiapas because that is too far and I don´t have the time, and I was mentioned Jaumave. What do you think and suggest?. Thanks a lot.