Perfect is a big word, and using it right in the title of your book invites close scrutiny. Tim Birkhead, a respected ornithologist with years of research under his belt, doesn’t quite achieve perfection with this book on the totality of that strange entity, the bird’s egg, but he makes a valiant effort of it and comes away with a very interesting book indeed.

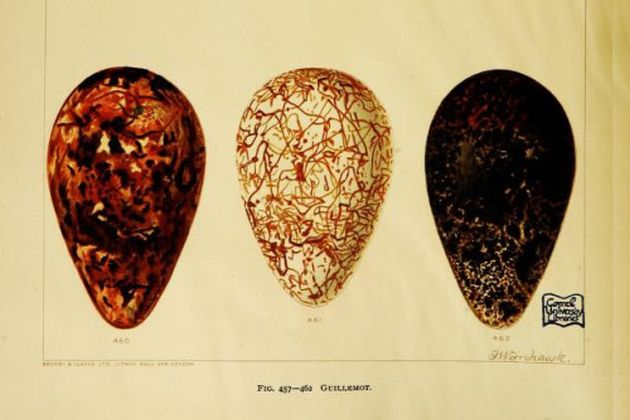

Birkhead’s remit includes not only science but the history of science, and as such he examines the egg in several dimensions: in space, considering the shell, albumen, and yolk separately in terms of their development, form, and function; in time over the life of the individual egg, from the fertilization of the ova through laying, incubation, hatching, and the disposal of the shell fragments; and in historical time, tracing the development of ornithology as a science and the comings and goings of various theories on how eggs evolved and why they look and act as they do (in particular, he returns again and again to the canard – pardon the weak pun – about guillemot eggs and their propensity to roll in a circle). While this extremely complex organizational scheme sometimes leads to repetition and back-tracking in the text, it also allows Birkhead to convey a vast amount of information in a memorable and entertaining fashion. From the antibacterial properties of the albumen to fact that chicks in a clutch can synchronize their hatching by communicating by clicks and peeps from within the shell, this is everything you ever wanted to know about eggs but had no idea you even needed to ask.

Of course, the line between entertaining and not is both thin and very personal. Birkhead sometimes lapses, especially when he attempts to be jovial in that old-fashioned British way that just doesn’t scan for a lot of people. Tiny but inexplicable asides like how eggs inspire collectors because they have curves like women (ask an egg-shaped woman how society regards her shape sometime) don’t really add to the proceedings; they don’t offend so much as they just baffle. More pervasive, and likely more difficult for the typical 10,000 Birds reader, is Birkhead’s appreciation of the egg collectors whose obsessions wreaked such havoc on so many bird populations — but also provided so much of the raw material for egg research, contributing to discoveries even today. Birkhead is not unaware of the difficulties here but he ultimately seems to regard these men warmly, as forefathers. Given the specifics of his project I can’t even entirely fault him for that. It is only that the philosophy behind this outlook deserves space that Birkhead does not — and probably could not, given everything else that is going on in this book — devote to it. It’s certainly not that Birkhead is insensible to the needs of conservation, given an epilogue in which he not only addresses the implications of climate change for egg evolution but also conducts a passionate and much-needed defense of long-term population studies as a conservation tool and describes how his own efforts with guillemots were nearly derailed by short-sighted bureaucrats, only to be rescued, for now, by crowdfunding.

So, most readers will find that this book does have tiny imperfections here and there. Nevertheless, as a rich and densely-packed source of information on a fascinating subject that most people, even most birders, are ignorant of, The Most Perfect Thing is hard to beat.

The Most Perfect Thing: Inside (and Outside) a Bird’s Egg by Tim Birkhead, $27.00

Leave a Comment