In 2009, I traveled from New York City to the tropical rainforest of Ecuador. It was my first trip to the Neotropics, and I had no idea what I was getting into. More than a difference in humidity and temperature, everything was different–from the hundreds of species of plants and trees, to the way the trees grew out and around and in and out rather than simply up, to the Morpho butterflies fluttering around those trees in dreamlike swoops that never landed, to the birds themselves, which did not behave like the birds back home (“Welcome to the mixed flock,” one of my friends said, as I tried to identify species, helplessly). Although there is something to be said for learning by immersion, I really wish I had read The Neotropical Companion by John Kricher BEFORE I got on the plane. And, the next time I travel south (and, there’s an excellent chance that will happen within the next year), I will definitely once more read The New Neotropical Companion, by John Kricher, the latest version of this nature classic.

The New Neotropical Companion describes, explains, and provides insight into the unique ecosystems of the Neotropics. That sentence really doesn’t begin to describe this very smart and highly readable book. In its third edition, it maintains and expands on the qualities for which it is known: a high level of knowledge, from classic studies to the most recent research; judicious use of scientific data–enough to illustrate key points but never used to intimidate; detailed explanations of ecological relationships in a friendly, occasionally chatty voice that never resorts to scientific gobblygook or a dumbing down of ideas and vocabulary. Written by an ornithologist who is also a birder and who embraces the world from an ecological viewpoint that sees birds as part of larger systems of evolution, succession, and mutualism, The New Neotropical Companion is the textbook-that-is-not-a-textbook you always wanted to read, though you may not know it yet.

The first edition, A Neotropical Companion: An Introduction to the Animals, Plants, and Ecosystems of the New World Tropics, was published in 1989. In a time of little published information about the rainforests of Central and South America aside from scientific journal articles and the works of 19th-century naturalists, the “little green book,” as it was called, became a must-read amongst nature-oriented travelers and researchers. An enlarged version was published in 1997, with color photographs and more coverage of South America. The ‘little green book’ was now over 450 pages long! The American Birding Association translated it into Spanish as part of its Birders Exchange Program, distributing copies to students and scientists in Central and South America and also making it available free in PDF format.

I think the many naturalists who value A Neotropical Companion will be very happy with this edition. It is beautifully produced–larger size, larger print, glossy paper that nicely shows off hundreds of photographs (and some maps and charts) integrated with the text. Whereas the second edition is almost purely text with some drawings and photographs in separate sections, this edition is designed from a visual perspective–large photographs accompanied by extended captions, boxed sections, section headings in large, bold text.

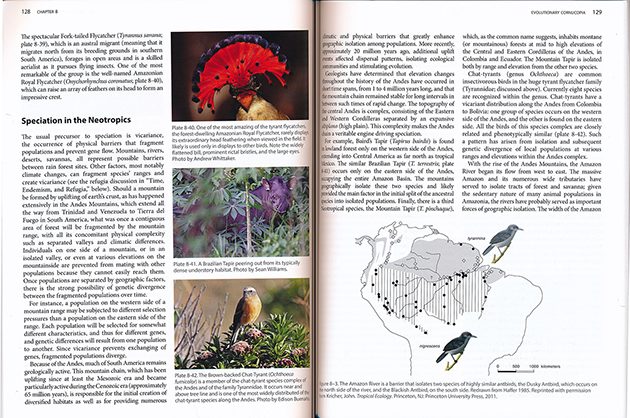

Kricher has expanded subject coverage and updated, revised, re-arranged, and rewritten text. There are now 18 chapters (an increase of four) delving into the climate, plants, animals, birds, and insects of the rainforest, its ecological and evolutionary processes, and, because the Neotropics are more than high humidity, its other major ecosystems—savannahs and dry forests, mountains, rivers. The text still focuses on Central and South America, though the Caribbean is also considered to be part of the Neotropics. One of Kricher’s goals with this edition, he says, was to write a book that was “less academic in tone,” something he felt he could do now with the publication of his college-level textbook Tropical Ecology (Princeton Univ. Press, 2011). This translates into style differences (studies are no longer cited formally with author and date), colloquial descriptions of studies, and a more conversational way of writing. It also allows Kricher’s graceful writing style to flow unrestricted.

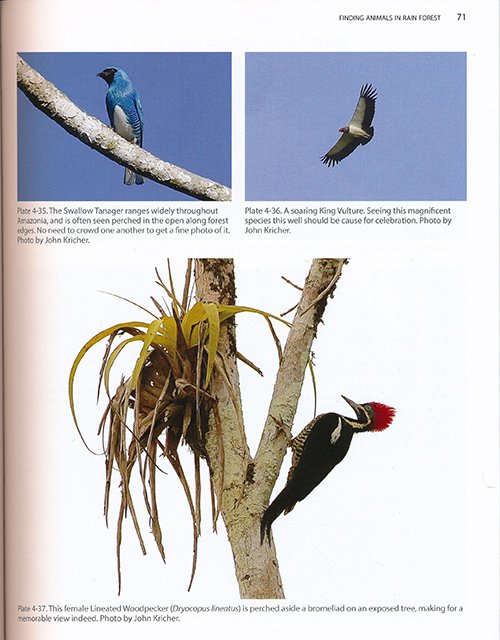

The photographs are by a group of nature photographers, guides, and birders, including Kricher himself, plus familiar names such as James Adams, Edison Buenaño, Gina Nichol, Dennis Paulson, and Clay Taylor. The photos are, I think, fabulous, from striking Contingas and Macaws to muted Wood-Quail and Woodcreepers; from a Lowand Paca caught at night with fruit in its mouth to a Tamunda anteater in threat posture; from a Katydid that looks just like a composing leaf to the adorable, colorful, deadly Poison-dart Frogs; from close-ups of spiny Palm tree trunks and to Andes vistas–the photos complement and expand on the text in addition to being a feast for the eyes. Colors are vivid and the photos are arranged carefully, sizes coordinated and balanced with the text. My personal favorites are the images that show the relationships that are at the heart of this book–a Linneated Woodpecker perched opposite a bromeliad on an exposed tree, Azteca ants on a cecropia tree whose decaying parts provide food, and, a little distressingly, two Capuchin Monkeys feeding on a Toucan (thanks to James Adams). Photographic credits are given with each photo, which I like better than a listing at the back of the book.

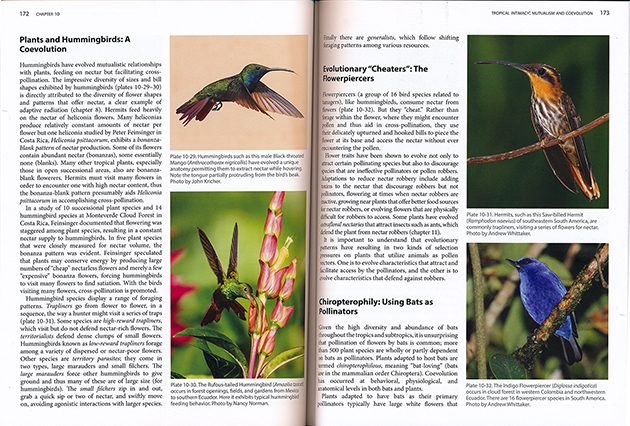

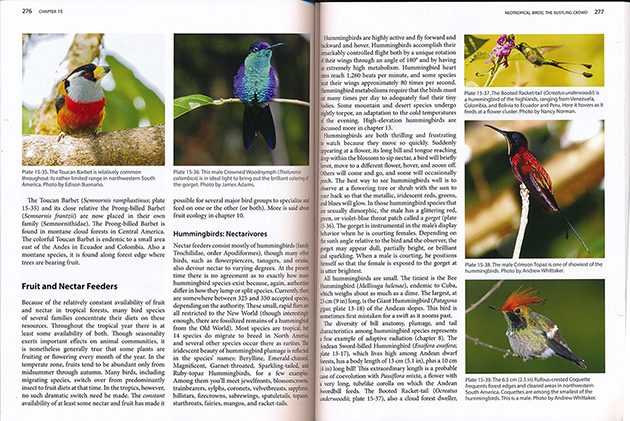

Birders will probably be most interested in the lengthy chapter (57 pages) on “Neotropical Birds: The Bustling Crowd.” Kricher delineates the many types of bird families and species you are likely to encounter in the Neotropics, emphasizing habitat and behavior (especially feeding behavior, and particularly fruit eaters; fruit is an important element when it comes to tropical ecology). Please–do not read this section only! This is a book about patterns and relationships, not a strictly partitioned reference book, and you will find material on birds in every chapter. Hummingbirds, for example, are of course in the Neotropical Bird chapter; they are also in the chapters on “Tropical Intimacy: Mutualism and Coevolution” (Feinsinger’s study of hummingbirds and the timing of flowering in the Monteverde cloud forest), and “Scaling the Andes” (Sword-billed and Giant Hummingbirds and Helmetcrest). You will miss out on some fascinating info and insightful background on evolution if you restrict yourself to chapter 15.

If you are about to embark on your first trip to the Neotropics and are strapped for time, I highly recommend chapter 4, “Finding Animals in the Rain Forest,” with its suggestions on observation (how exactly do you SEE species that remain in the canopy?) and Kricher’s Top 10 Tips of Trail Etiquette (“etiquette demands some measure of sharing….try to resist one-upmanship”). This is a man who has intimate knowledge of birding tours. Also a must for travelers: the appendix entitled “Words of Caution: Be Sure to Read This,” which details the threats of certain invertebrates, like mosquitos, chiggers, ticks, and botflies (ick). This section is much shorter than the appendix in the second edition, which also included the dangers of urticating caterpillars, snakes, “Montezuma’s revenge,” altitude sickness, etc. I wonder if it was cut to save space or because it discouraged Neotropical ecotourism; the section on snakes was particularly scary.

Though each chapter offers a wealth of mind-boggling knowledge, I particularly enjoyed the chapter on “Tropical Intimacy: Mutualism and Co-evolution,” with its examination of species interdependences and evolutionary oddities. This is where fruit comes into play. Oilbirds eat fruit. How did that happen? Certain tropical birds, like Guianan Cock-of-the-Rock and Manakins, are known for the male’s colorful plumage and elaborate courtship rituals; apparently fruit is the reason they do that. I’m not going to explain these evolutionary developments here; you’ll have to read the book. Walking through Neotropical rainforests is like walking through a wonderland of constant interactions amongst plants, birds, insects, reptiles, and mammals, which are in turn the consequences of hundreds of years of adaptation and evolution, and you can see it happening right in front of you. If you know what to look for and if you understand how to interpret what you’re seeing.

Back of the book material consists of an extensive (25 pages) reading list, modestly titled “Further Reading,” and a detailed Index. The reading list is nicely divided into “Oldies But Goodies,” “General Reference: The Essentials,” and “Chapter-by-Chapter Further Reading Lists,” with books and articles used as references and sources for the writing of the book printed in bold lettering (another improvement from the second edition). Field guides are included for the Neotropical Birds chapter, but otherwise, this is primarily a scientific list; no websites or online articles are listed except for a group of website articles on hydroelectric dam projects in Amazonia. The Index is excellent, listing topics, authors cited, species, and places. I only wish that the page numbers of photographs were differentiated in some way from text references. Sadly, the Glossary of the second edition did not make it into this book.

John Kricher is professor of biology at Wheaton College, where he teaches Ornithology, amongst other courses; he has written general and scientific books and papers on North American migrant birds on their Neotropical wintering grounds, ecology, trees, and dinosaurs. He has led birding tours, taught at Hog Island Audubon Camp, made presentations to many birding and ornithological associations, is a past president of the Wilson Ornithological Society, the Association of Field Ornithologists, and the Nuttall Ornithological Club, and is currently on the Council of the Massachusetts Audubon Society.

I looked up most of Kricher’s biography on the Internet because his bio on the back book cover is very brief and I wanted to know a bit more about the education and experience he brought to this uncommon book. Reading between the lines, beyond the degrees and publications, his commitment to education, the birding community, and the birds (and mammals and reptiles and insects and plants, etc.) is remarkable. It has resulted in a Neotropical ecology book for these times–intelligent, visual, readable, and very concerned about saving this species-rich, huge but vulnerable area. The chapters on “Human Ecology in the Tropics” and “The Future of the Neotropics” succinctly describe the amount of damage humans have wrought on the rainforests and outline the complexities of current conservation initiatives.

For some of us, like that version of myself that traveled to Ecuador eight years ago, the Neotropics are simply a place to visit. But, there is no place comparable, no place with as much biodiversity, no place that North American birders fall in love with more (just ask fellow beat writer Patrick O’Donnell). If you are planning to travel to Central or South America, The New Neotropical Companion is the book to read. It won’t teach you how to identify birds. It will teach you how to appreciate their evolutionary development, and recognize their adaptive behavior. It will explain the process of forest succession, the dynamics of drought, the power of climate, the difference between leaf-cutter ants and army ants, the magic of mimicry. It will prepare you to walk through the rainforest and observe Neotropical birds. You may even begin to feel a sense of belonging in this very different world. And then, you can begin to think about identification.

The New Neotropical Companion

By John Kricher

Princeton University Press, 2017

Paperback, 448 pp., 7 1/2 x 9 1/2 | 18 color illus.

ISBN-10: 0691115257; ISBN-13: 978-0691115252

eBook – ISBN: 9781400885589

Kindle edition: $22.05; iBook: $24.99

$35.00, discounted by the usual suspects.

Leave a Comment