Icterus is a wide-ranging neotropical genus consisting of the technicolor blackbirds we call orioles. The two dozen species are, nearly to an individual, long bodied and bicolored. Most make impressively woven, deep, nests, and eat insects and nectar, often coming to feeders well-stocked with oranges and jellies. In North America, at least in the eastern part of it, we celebrate the return of the Baltimore Oriole to parks and farms this time of year. And given that its image is prominently featured on the logo of a professional sports team it’s likely considered the type specimen for its genus. The prototypical oriole.

But that would be incorrect.

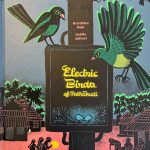

Icterus galbula is a handsome bird, to be sure. But it is not the oriole to which all other icterids should be compared. No, far to the south lies Icterus icterus, which despite the common name of Venezuelan Troupial, is the most oriole oriole of them all. I will broker no argument to the contrary. Take a look at this sucker.

For starters, it’s massive. Baltimore Orioles are surprisingly slight when you get a look at them, but troupials are about the size of a jay, and with the bearing to go with it. It was one of my A-1 targets when I visited Aruba, and I was pleased to realize that I needn’t have worried too much about seeing it. While they’re not as plentiful as the ever-present Eared Doves, Venezuelan Troupial is hardly a rare bird on the windswept island, and once you key into their lyrical, rambling song, they’re easy to find, though admittedly their preference for the very tops of the few trees on the island made it more or less difficult to get a nice photo.

While walking along the beach one morning, I noted a fruiting Dagger Cactus right near the beach, at the top was a bird just destroying one of the purple fruits near the top of plant’s formidable crown. There is no doubt about it, this is a striking bird. Not only are you dealing with an oriole with the standard appropriation of orange and black you expect in that group, but that massive blue based bill and, especially, the eye, hypnotic yellow and surrounded by a mask of blue skin, is too much.

Unlike most of its cogeners, Venezuelan Troupial does not build one of those hanging bag nests so well known by the other Icterus species, it’s a nest parasite. This revelation shocked me when I first read it, but as it it turns out the troupial is not one of those next parasites and lays and leaves like North American cowbirds and cuckoos in Europe. Troupials raise their own chicks, generally 3 to 4 per clutch, they just steal the nest in which they raise them. Granted, occasionally these nests are themselves, occupied, and the troupials are not averse to kicking out the previous occupants – eggs, chicks, and all – but rest assured they are not dead-beat parents. Just lazy ones.

I have yet to see one of our North American orioles this year, though I expect I’ll come across either the Baltimore or the Orchard variety in the not to distant future, but should I miss them I feel as though my oriole quote for 2013 has been reached. After all, there are likely none more oriole than Icterus icterus.

Fascinating, Nate. How funny that the troupial is a nest parasite when so many orioles are known for their elaborate pendulous nests.

I might also quibble that instead of the oriolest oriole, the troupial is more like the icteridest icterid. It definitely reminds me more of oropendulas and some of the other large-billed icterids than our tiny-billed continental orioles.

What a beautiful bird! I like how orange it is.

Apart from the fact that I am with Mike (because the oriolest oriole surely must be Oriolus oriolus 😉 ), this bird is un-flopping-real!! A brainbird that made my day!! Thanks for introducing me to my desire to visit Venezuela … like … NOW!!! 🙂

Wow, it’s liike that Reese’s commercial (“You got your peanut butter on my chocolate!” “Your chocolate is in my peanut butter!”), instead using “oriole” and “grackle”. What a treat for you to see!

Wow! That is the most gracklest looking oriole I’ve ever seen. Beautiful bird.. I wonder if there has ever been a crow version, too.

I took a picture to one of this bird in my backyard. I live in Miami, Florida.

we have spotted a orioles for the last few days never seen it before. we are out side of Rochester N.Y. found it on this web page will try to take a picture. Are they commend to this area ?