All right, I’ll admit it. I’m feeling pretty good about myself right now. I came back from a Monday birding trip and told my wife, prior to reviewing my photos, that I saw a bird that was either 1) interesting, or 2) historic. It turned out to be historic, if only on a local, very birdy level. And the bird in question even allowed me some great photos!

As for the title of this post, well… I’m not that cocky. The secrets of my success in this case are the same as for any other birding successes I have had:

- Dumb luck

- Perseverance

- Being the only guy around to discover something. Or, as goes my unofficial motto: In the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king.

Please excuse me if I take the long way around to tell this story. On May 23, I decided to go up to Lake Cuitzeo, in spite of the fact that the lake can seem much less interesting after our winter migrant ducks, waders and shorebirds have left. In part, I just wanted to see how much of the lake made it through the dry season this year, since our summer monsoons are just about to start.

As it turned out, perhaps 80% of the lake made it through the dry season. And it also turned out, to my great surprise, that not all those migratory ducks had left yet. What were several Northern Shovelers and one Blue-winged Teal doing, hanging out with our resident Fulvous Whistling-Ducks on a May 23rd?

This is not normal in late May.

This is normal in late May.

Then there was the Northern Cardinal that turned up at the pre-Columbian Tres Cerritos ruins on the lake’s north shore. I’ve never known quite what to do with the two Cardinal sightings I have had near our church in Morelia, since that species is not supposed to be seen there, or to be migratory, but both sightings occurred in winter. But Cardinals certainly do seem to be residents at Tres Cerritos, in spite of being well south of their official range; I have so far seen them there in seven different months of the year. And I found this one because he was singing his heart out quite persistently, which certainly suggests a bird that wants to settle down and raise a family.

These images may not be a big deal to many of our readers. But they kind of are, down here. [Update: I went back the following Monday, and this male was still there, and still singing. Also, there was a pair nearby. So yes, this appears to be a breeding population.]

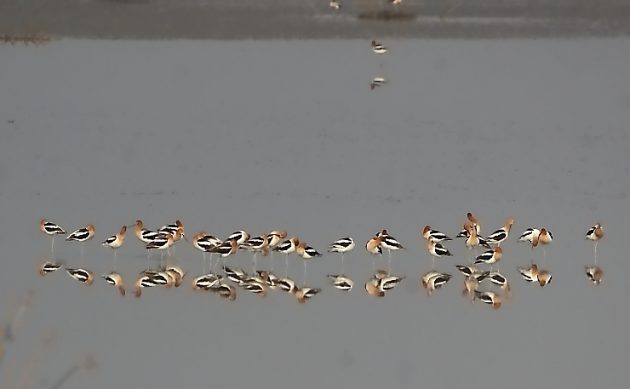

There were many other pleasures on the way to my big moment, of course. The Black-necked Stilts and American Avocets certainly seemed to be interested in impressing the ladies — very frisky and full of themselves. And since I don’t go to the lake very often in late spring, I rarely get to see these Avocets in their breeding plumage. (Avocets are a simple black and white in midwinter.)

A cute pair of Bushtits (the Mexican kind, with masked males) also seemed to be nest building, even though the male clearly had a broken bill. Good for him, for not letting that stop him from building a legacy!

Not only that, but the Gulls were Laughing, and the Terns were Forster’s — a nice change from winter’s Ring-billed Gulls and Caspian Terns.

Not an immature Ring-billed.

Not a mature Ring-billed.

Not a Caspian.

Still, it was just one more birding day, although a very pleasant one, until I happened to notice a single medium sized shorebird, just off the, well, shore. It was quite a ways away when I took my first photos, but I already suspected that it might be a Godwit.

I have seen two Godwit species at Lake Cuitzeo. One is unusual, the other is extraordinary. The Marbled Godwit is, by Godwit standards, an unambitious bird, mostly limiting itself to a single continent. Most Marbled Godwits breed in inland North America, and winter along the tropical coasts of Mexico and the Caribbean.

In contrast, the Hudsonian Godwit is one of the few birds that fly the length of the world each year. They breed along the Arctic Circle in Canada and Alaska, and winter in southern South America, often in Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego. They sometimes fly the length of the world nonstop on their way south, but, fortunately for birders, may stop on their way north.

Last year, there were eight Hudsonian sightings reported on eBird for Mexico. Only one, in Mexico City, was far from the coast. 2020 yielded a single sighting; 2019, two; 2018, four.

In 2018, I took a photo of what I thought was a trio of Dowitchers on Lake Cuitzeo. Then dumb luck (really dumb on my part) struck, and a much better birder who happened to look at my eBird report informed me that my birds were, in fact, Hudsonian Godwits — by far the first ones ever reported this far west in Mexico. Would this 2022 bird be another one?

I am not ashamed to say that I took some 420 photos of this bird. The first were from far away, too far for a sharp image; but one never knows when the window of opportunity will close, so I clicked away.

Still, after taking those shots, I settled into the hopeful birder’s gait: advance slowly, take some photos, advance a bit more, shoot some more… Imagine my surprise when this bird continued to calmly feed even when I reached the end of the walkable ground, only a few yards away! Apparently being tired and hungry trumps everything else, when you’ve just flown from Patagonia to Mexico. For my Godwit was indeed Hudsonian, and in full mating plumage.

You may ask why I was so excited about my second sighting of this species? Here is my reasoning: One sighting could indicate a vagrant bird, which is very, very cool, but not really significant for science. Two sightings in the same place and of the same species, however, is a discovery. It means something.

So yes, I am feeling pretty good right now. It is good to be the king. Even if I am only a one-eyed king, in the land of the blind.

Great photos, Paul! And of course, I immediately started wondering whether “The secret of my failure” is a good title for a future blog post of mine.