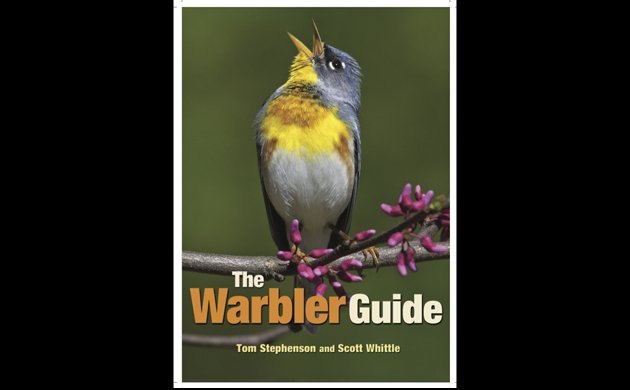

Imagine a world without warblers. No small songbirds feeding like moving jewels in the canopy. A distinct lack of birdsong on a May morning. “Warbler-neck” would become “kingbird-neck” or “gnatcatcher neck”. Without birds like Blackburnian Warbler to spark people’s interest in birding, we would have far fewer birders. (Famously, the Blackburnian was the spark bird for notable birder Phoebe Snetsinger; it was also the spark bird for my friend Marylee,.) Without warblers, migrant hotspots like the Ramble in New York City’s Central Park would be empty in May. And, without warblers we would not have the bibliographic joy of books like The Warbler Guide, by Tom Stephenson and Scott Whittle, a warbler feast for the eyes, the answer to the prayers of every birder who has seen a glimpse of yellow, black, and white and said, “If only that leaf wasn’t in the way, I’d know that warbler’s name.”

Many birders are already familiar with the concept of The Warbler Guide. A series of videos on how to use the book’s features have been made available on the book’s Facebook page and the Princeton University Press Blog, and Tom Stephenson and Scott Whittle have been presenting workshops and talks on warbler identification and vocalizations across the country, including one I attended in April at the Queens County Bird Club, NYC. The videos and talks have wet our appetites for a book that promises to be visually exciting and fun to use, designed by birders who have used their own experiences in the field to determine what warbler seekers really need. Tom Stephenson is a professional musician who recently retired as director of technology at the Roland Corporation. He has been birding since he was a kid, led birding trips across the U.S. and in Asia, and his photos and articles have been published in many publications, including Birding and Birdwatcher’s Digest. Scott Whittle has twenty years experience as a photographer and at one time, fairly recently, held the New York State big year record. Both men have been active in the Brooklyn Bird Club; Scott currently lives in Cape May. These are birders of talent who know their warblers and their audience.

The Warbler Guide focuses as probably no other book has before on warbler identification, visually and auditorially. There are six sections:

(1) Introductory material on how to use the book, how to look at a warbler and how to listen to warbler songs, chips, and flight calls;

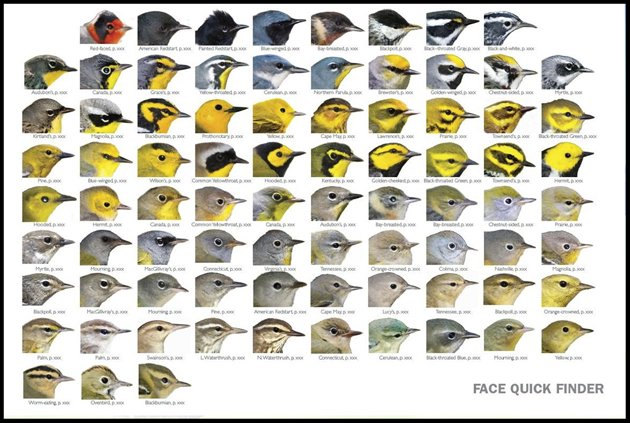

(2) A substantial section of “finder guides” and charts, like this Face Quick Finder (above);

(3) Species Accounts, the heart of the book;

(4) Quiz and Review;

(5) More identification materials, including Warblers in Flight, taxonomy, measurements, a chart on Habitat and Behavior;

(6) End of book material, including a Glossary and Resources.

I’m going to go right to a discussion of the Species Accounts, because I know that’s where you all want to be, with the warblers. The Warbler Guide covers 48 warblers commonly seen in the United States, arranged in alphabetical order. It’s an organization prompted by recent changes to warbler taxonomy. The authors feel that following these changes would be confusing and time consuming to birders used to the old system. (There’s also, I suspect, an unspoken fear that taxonomy may change again in the future, rendering any taxonomic-based organization obsolete.) Alphabetical order works fine, as long as you remember that it’s American Redstart if you live in the east, not Redstart, and that it’s Yellow-rumped Warbler, not Audubon’s or Myrtle Warbler. I do love the fact that the table of contents lists all three names (all pointing to the same species account). Yellow-breasted Chat and Olive Warbler are listed in a section on “Similar Non-warbler Species”, but are given similar descriptive coverage as the “true” warblers, though not as extensive. Similarly, seven casual visitors, such as Fan-tailed Warbler and Tropical Parula, get two-page accounts at the end of the Species Accounts section.

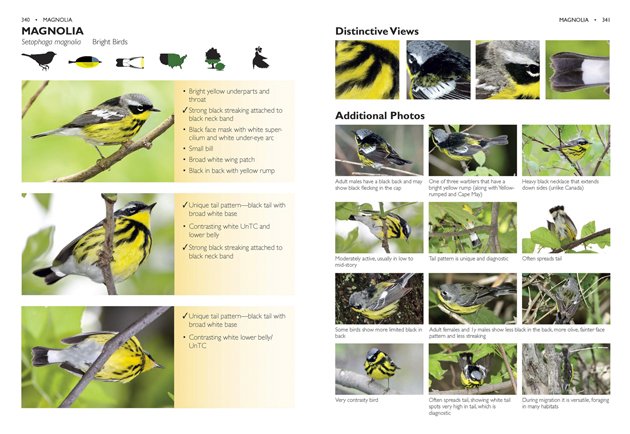

I very much enjoy using the Species Accounts; they are a model of informational economy, communicating a lot of information quickly and easily through graphics and design, photographs and minimal text. Each account starts off with the common and scientific name of the bird This is the traditional way. But, then, aha! there is a row of six icons: a tiny silhouette showing the shape of the bird; a tiny color coded bird, showing its colors; a tiny tail as seen from underneath; a tiny map showing the part of the United States where the bird is commonly found; a “preferred habitat” icon showing whether the bird prefers the high canopy or the ground of somewhere in-between; and a “behavioral icon” denoting specific typical, sometimes diagnostic behavior, such as sally feeding, tail bobbing, and trunk creeping.

So, these Magnolia Warbler icons, what do they mean? This rather short-tailed bird perches perkily and horizontally in the understory. It is a bird of black and gray uppersides and yellow and white undersides, with a black tail that, when seen from underneath, is broadly black at the tip with a white base and white undertail coverts. Magnolia Warblers are found in the central and eastern United States. They are hover-gleaners, birds that feed while flying or hovering in the air, picking insects off of foliage (this definition is straight from the Glossary at the back of the book). I got all that information from six tiny icons.

Next, after the icons, are the photographic views of the bird from three angles—side, three-quarter view, and from underneath, with accompanying bullet points on physical features and diagnostic behavior. Checkmarks are placed next to diagnostic field marks that can be relied on by themselves for “a confident ID”. Page two of each species account offers “Distinctive Views”, “Additional Photos” and notes. The distinctive views are one of the best parts of The Warbler Guide. You know how maddeningly frustrating it is when you only can see parts of a warbler in that annoyingly high canopy? Here is finally an identification guide that shows these parts!

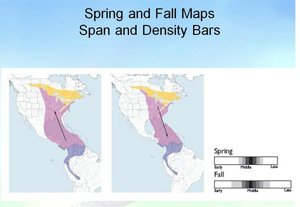

Migration maps delineate spring and fall migration routes separately. The dual map system is also used by Donald and Lillian Stokes in their Stokes Field Guide to Warblers. But, while the Stokes show expected migration dates with lines across the map, The Warbler Guide employs separate “span and density bars”, showing at what point during the season migration becomes most intense and for how long. These are much prettier maps, and probably more useful in terms of applying the timing of migration waves to where one lives, but I miss the calendar aspect of the smaller book’s maps.

The “Aging and Sexing” section illustrates just that, the male and female bird at different life stages—adult male, first-year fall female, first-year spring female, etc. The authors note when a species cannot be sexed or aged with certainty. It is very helpful to read the introductory material in the first part of the book to fully understand molt, the context for aging and sexing, and the information shortcuts. It’s not just the abbreviation letters you need to know in order to use this section well; color coding indicates whether or not age and/or sex can be determined reliably or if certain factors need to be considered. This can get complicated. A red/green combination means “it is always possible to identify a male bird, but it is impossible to age the bird.”

It was when I studied the “Aging and Sexing” page for Blackburnian Warbler that I realized how different The Warbler Guide is from previous warbler identification books. It’s the difference between pure text and visuality, between presenting the whole and focusing on the prime details. Jon Dunn and Kimball Garrett’s A Field Guide to Warblers of North America, part of the Peterson Field Guide series, devotes three pages to the “Plumages and Molts” of the Blackburnian Warbler, describing in detailed, dense text eight plumages: spring adult male, adult female, first spring female, fall adult male, first fall male, fall adult female, first fall female, and juvenile. Only two photographs illustrate this lengthy section. The Warbler Guide’s “Aging and Sexing” Blackburnian Warblers takes up less than a full page, but features six photographs of six plumages: adult male/first-year spring male, adult female/first-year spring female; adult male fall, adult female/first-year male fall; first-year male fall cheek patch, and first-year fall female. The text for each photo is brief, focused on diagnostic features. The goal here is to give the information the birder needs, no frills. The goal of A Field Guide to Warblers is to give comprehensive information, everything that can be squeezed into the page.

Comparison species are treated in depth for each species in The Warbler Guide. In this plate, for example, we learn how not to confuse Blackburnian Warbler with Bay-breasted, Blackpoll, Cerulean, Cape May or Palm Warbler. It may seem ridiculous that the brilliant Blackburnian Warbler can be mistaken for any other bird, but that’s because we usually don’t think of the far less striking fall and female Blackburnians. Which brings us to a unique feature of The Warbler Guide, the division of certain species accounts into “Bright Birds” and “Drab Birds”. This is the case here; this Comparison Species page is from the “Blackburnian—Drab Birds” section. The comparative species list for the “Blackburnian—Bright Birds” section is totally different–Yellow-throated Warbler and male American Redstart. “Drab Bird” sections even have their own set of icons and bullet points, which makes sense when you think about it. It can be confusing if, like me, you are a browser, who likes to find items by flipping the pages instead of using the index. Although this is basically an easy book to use, there are certain features that require a few minutes of a learning curve.

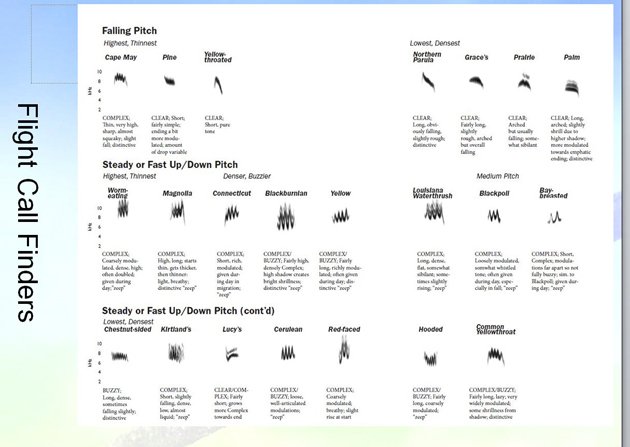

Which brings us to the aspect of The Warbler Guide that I find particularly challenging, the auditory aspects of warbler identification. The book pays as much attention to warbler songs, chips, and flight calls as it does to what warblers look like. The introductory section includes chapters on “How to Listen to Warbler Songs,” “Learning Chip and Flight Calls,” and “Understanding Sonograms”. The Finders section includes a 14-page Warbler Song Finder Chart and 4-page Chip Call and Flight Call Finder charts. The charts employ sonograms, “graphical representations” of sound. Each species account features sonograms of the species’ songs and a comparison with sonograms of similar warbler songs.

I had heard Tom Stephenson describe his analytic system for identifying birds at the Queens County Bird Club and I was anxious to read more about it. I am one of those birders who sees birds a lot more easily than I can hear them. It’s not just the hearing itself, it’s the sorting out of the different buzzes and trills and whistles. Stephenson feels that using sonograms and a system of Elements, Phrases, and Sections will help birders make better sense of bird vocalizations and increase the ease and quickness of warbler identification. Using sonograms is not new. Donald Kroodsma employs them in his books about bird song; the Cornell University Lab of Ornithology promotes them and offers a link to Raven Lite, free software that allows you to visualize sound. But, I don’t think there is a bird identification guide around, on warblers or any other bird family, that has invented its own analytic system.

I’ve tried to learn the system, it’s not easy. It was difficult to learn how to use the sonograms without actually hearing the sounds, and I ended up using my own birding apps as I read the text. Which was time consuming. Princeton University Press reports that the authors will be making “a library of warbler songs and sounds available via their web site” by the time the book is published, in early July. I am very much looking forward to it. I do think that other birders, especially those with backgrounds in music, will find the system much more accessible. In fact, many of my friends who also attended Tom’s QCBC presentation were fascinated by the system, and drowned Tom in questions about how they could make their own recordings and sonograms.

There are so many excellent features of this book that I would like to talk about. I love the Finders–the Face Quick Finder shown at the beginning of this review, the Side Quick Finder, the 45-degree View Quick Finder, the Underview Quick Finder, and the Finders for East Spring, East Fall, the West, Eastern and Western Undertails. The plates are just scrumptious to look at. I hope PUP comes out with posters soon! The Quiz and Review section offers a good way to practice identification in the field while at home. The authors reason out each bird’s identification slowly and conversationally, showing how identification is not always a 1-2-3-gotcha process. I was a little disappointed that the brief section on Hybrids presented only 7 examples, but this is a field that is still filled with many unanswered questions and uncertain identities.

I liked the Glossary. It includes terms from the auditory sections as well as more typical bird anatomy and plumage terms. The Resources section is very brief. It lists all major books on warblers, a couple of audio collections, selected Research Papers, selected Web Resources, a very selected list of Birding Festivals, several Apps, and, a nice touch, a note on the American Birding Association and the greatness of local Audubon societies. I have to make a librarian note about the research paper citations–where are the years of publication? This is a must if you are going to list scientific articles. The Index is all too brief, listing only species by common and scientific name. Main Species Accounts and Comparative Accounts are differentiated, which is good. But, I think the introductory chapters should be indexed as well, listing concepts such as pitch and song structure.

The Warbler Guide, by Tom Stephenson and Scott Whittle, is not just another bird identification book. Like The Crossley ID Guides, the authors have thought long and hard about what makes an identification guide work and then approached it their own way. The auditory descriptions of bird song and chips, based on scientific analysis rather than a subjective translation of sound, present a very different approach to identifying birds by ear. The abundance of photographs, the plethora of charts and finding guides, all printed in brilliant color on lovely paper, the clarity of design, make this book a joy to look at and to use. Be warned that this is not a field guide; it is too thick and heavy to carry in one’s pocket or even a backpack. I do think that birders will get a lot of use out of using it in the car, on the bench, or next to the computer as they try to puzzle out their warbler photographs. This is definitely a book experienced birders, especially those in central and Eastern United States, will want to buy. Western birders, I’m sorry, but you do have far fewer warblers, and in a world without warblers we would not be able to tease you about that. But, I think you would enjoy having this book too. I am on the fence about whether this is a good book for beginner birders. I think the Stokes Field Guide to Warblers (2004) and Chris G. Earley’s Warblers of the Great Lakes Region & Eastern North America (2003) may be far less intimidating choices. I would be very interested in hearing your opinions about this question. I’d also like to know if you’ve tried The Warbler Guide’s system for identifying songs and if it works for you.

There is more Warbler Guide to come. Princeton University Press promises an app and an enhanced ebook in the spring of 2014. I hope by that time I will know the sonogram of every warbler by heart. And, I hope that we never have to experience a world without warblers.

The Warbler Guide

by Tom Stephenson & Scott Whittle

Drawings by Catherine Hamilton

Princeton University Press, July 2013.

560 pp., 6 x 8 1/2, 1,000+ color illus. 50 maps.

Paper Flexibound, ISBN: 9780691154824, $29.95, £19.95.

eBook edition, ISBN: 9781400846863, to be published.

I’m confused. The title implied this book would be about warblers, a challenging if polyphyletic group. But the article seems to be about New World warblers!

Speaking of the west having fewer warblers, almost every species I saw in California. Pretty much all the east coast species end up there on their way home! They aren’t very good at navigating!

Duncan, you are correct. The title of the book should be The New World Wood Warbler Guide, or TNWWWG. What can I say? We New World birders are a very self-absorbed lot. We also think Robins are thrushes.

As for warblers in the West, I think you were probably lucky to see them all there. My friend Woody, who is a naturalist in Seattle, keeps telling me he is coming to the east to get a good dose of wood warblers. I just looked up migration maps for Northern Parula, Pine, and Prothonotary Warblers, and none of them should be migrating through California! Are you really really sure you saw these warblers there?

I should have been clearer, I meant every species I have seen. But I saw a lot of east coast vagrants because I lived in the Farallones, a real migrant trap.

I’m no birder per se, but I think I saw a yellow rumped warbler in the Seattle area…. March of this year. Wasn’t around for long. Is it unusual?

Linda, there are two distinct subspecies of Yellow-rumped Warbler–the “Myrtle Warbler” which is found in the east, and the “Audubon Warbler”, which is found in the west, your area.

Birdweb, a web site from Seattle Audubon, offers an excellent species account for Yellow-rumped Warbler: http://www.birdweb.org/birdweb/bird/yellow-rumped_warbler Look under the tab “Find in WA” for a listing of regions and how common or uncommon they are in each region for each month. It says “The Myrtle form of Yellow-rumped Warbler is a common migrant and winter resident in Washington.”