Some years ago I was birding in the hills outside Ranikhet, in Uttarakhand, in the foothills of the Himalayas. We had seen an interesting selection of birds, including Streaked Laughing Thrushes, Grey-winged Blackbirds, Rufous-cheeked Scimitar Babblers and a Scaly-bellied Woodpecker, but nothing unexpected. Then, suddenly, our guide, Gajendra, got excited. He enthusiastically pointed out a pair of pigeons perched towards the top of a distant tree. I focussed my binoculars on them, hoping for one of the local specials, a Speckled Wood Pigeon, or perhaps an Ashy Wood Pigeon, both of which are resident in the north-east Indian hills.

However, it took no more than no more than a glance to identify the birds, for they were a species I was already very familiar with – (Common) Wood Pigeons. It wasn’t a bird I was expecting, as they are a scarce and localised bird in the Himalayas. Gajendra was clearly delighted to have found them for us, and I felt a bit mean when I told him that the Wood Pigeon was a very common bird at home in England, and one I see every day. It’s rare for there not to be a Woodie or two in my garden, prospecting under the bird feeders, or perhaps siting on the roof of the house, cooing away.

This Woodie was photographed in my garden in March – these birds are resident thought the year

The Wood Pigeon is so common that most people take it for granted. It breeds almost everywhere throughout the British Isles, and is only absent from some of the higher mountains in Scotland, and some northern and western isles where there’s little in the way of woodland, for as its name reminds us, this is a Wood Pigeon. However, Arable Pigeon would be an equally apt name, for it reaches its greatest abundance in the arable eastern lowlands of both Britain and Ireland.

Wood Pigeons are regarded in Britain as a serious agricultural pest

The British population is estimated at rather more than 5 million pairs: it increased by 169% between 1967 – 2010, but in recent years the population has stabilised, and there was even a slight decline during the last decade, though numbers seem to be rising once again. It’s presumably this recent slight dip in numbers that caused the Woodie to become Amber Listed on the list of UK Birds of Conservation Concern, but I don’t really think that even the most ardent pigeon enthusiast is in the least bit concerned about the current status of Columba palumbus.

Though I think I might struggle to find many people to agree with me, the Wood Pigeon is a handsome bird: full-breasted, small headed and long-tailed, it’s a classically shaped pigeon. Its dove-grey plumage blends into a subtle pink breast, while there’s a prominent white collar that adds a smart finishing touch to the plumage. When it flies, it flashes a broad white wing band. It’s not a difficult bird to identify. It sings throughout the year to remind us of its presence, with its soporific cooing one of the most familiar sounds of the English countryside.

Winter flocks of Wood Pigeons can number thousands of birds

It’s one of the few native birds that can be shot in Britain throughout the year, for it is regarded as a major agricultural pest. There are no bag limits. Dedicated pigeon shooters regularly achieve huge bags, usually shot over decoys, with totals of 100 birds in a day not unusual. The record for a single shooter in one day is over 700. The curious thing is that such enormous bags seem to have little impact on pigeon numbers. In my youth I spent a lot of time pursuing Wood Pigeons, and once, shooting with a friend, we bagged 96 birds, shooting over wheat stubble. Days like this remain long in the memory, but there were many occasions when I hardly fired a shot. Incidentally, it’s worth noting that Wood Pigeons are generally regarded as fine eating: a classic recipe is pan-fried pigeon breast with red wine, spinach and bacon. I can recommend it.

The Wood Pigeon is a popular quarry species in Britain. This bird has been retrieved by a Hungarian wirehaired vizsla

One of the reasons for the Woodie’s abundance is its productivity. Like all the pigeons, it only lays two eggs in a clutch, but here in Britain you can find eggs in almost every month of the year, though productivity peaks in the summer, with the greatest number of chicks fledging in August when food is at its most plentiful. Figures from the BTO show that these birds first nest when they are a year old, while ringing has revealed that though the typical lifespan is just three years, individuals can live much longer, with the current record 17 years 8 months and 19 days.

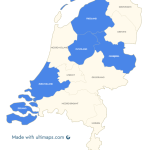

In northern Europe Wood Pigeons are migratory, with great numbers flying south every autumn. Most are heading for the cork-oak woods of central Spain, where they feast on the acorns. Ambushing the flocks as they fly through the Pyrenean passes has long been a favourite sport of French chasseurs (hunters). Here in Britain we regularly see large flocks in autumn, but most of our birds are sedentary, seldom moving far from where they were hatched. Recoveries of British ringed birds on the continent are surprisingly few, with most having flown no farther than across the English Channel to Northern France.

The trend towards milder winters suits the Wood Pigeon, which suffers badly in cold winters

It’s not just Britain where the Woodie is so abundant: it is equally numerous throughout much of northern Europe. Many reasons have been suggested for its success, of which the most plausible seem to be its adaptability, for it is equally home in city centres and urban parks as it is in the countryside. It was first recorded moving into city centres (including Paris and London) 200 years ago, but this is a process that is still continuing, with birds establishing themselves in Finnish and Swedish cities in recent years. Warmer weather and milder winters suit it perfectly, as does the widespread planting of oil-seed rape, an important winter food. A large estate near my house stopped growing rape because its crops were raided so badly by marauding flocks of pigeons.

Incidentally, the Wood Pigeon is predominately a European species, but it does breed in North Africa and the Middle East, while the birds I saw in India were on the extreme eastern edge of their range. The Woodie does have a North American equivalent, the Band-tailed Pigeon, which is similar in size and proportions.

The Wood-Pigeon is a very handsome bird indeed, clearly seen in these beautiful pictures that David showed. Look at that pink wash, that bi-coloured beak. And yes, really nice eating – the breast is called “poor man’s steak” in some countries… I really enjoy these posts about common yet interesting birds.

The flocking in large numbers remind me of the Paaenger Pigeon which were hunted to extinction.

Unless I am mistaken, the British murder myster series Midsomer Murders with Chief Inspecter Barnaby has the cooing of the “woodie” in many of its episodes.

Just a thought … for some of these essays, would it be possible to put in links to the bird’s song?