The other day, Redgannet, when sharing the 10,000 Birds combined bird list for 2016, mentioned that I had made some sort of notable contribution by submitting 25 checklists in one day. That sounds exciting, like there’s some sort of story there. But the truth is perhaps more pedestrian. This is the standard eBird pelagic protocol, which encourages birders to submit a new checklist every 30 minutes or so. For a trip offshore, which can range from 10-12 hours, this adds up to a lot of checklists.

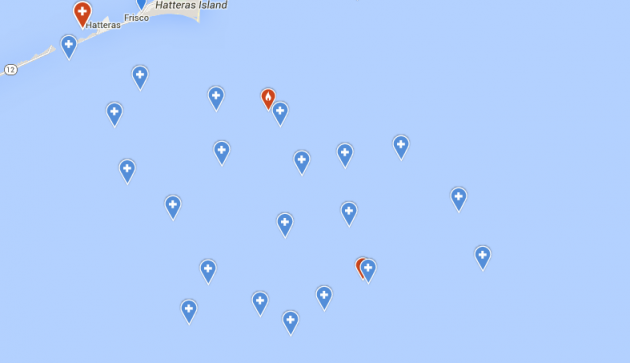

The reasons for this protocol are as unique as this unique type of birding. Though the ocean looks like one big expanse of blue, there are actually distinct biomes within that blue, mostly beneath the surface and mostly invisible to those who might not know what to look for. More, those biomes are constantly moving and waves and wind and, especially, the powerful Gulf Stream drives them northward. Conditions, and birds, can be wildly different from one day to the next out there. So any one hotspot can’t really contain the dynamic multitudes. A side benefit is that, if you’re an eBird junky like me, you get a cool collection of personal locations out near the continental shelf, a testimony to hours and days spent in this incredible place and the ways changing conditions can affect your route. And in fact, that farthest east cluster was this past trip, the farthest east into the ocean I’ve ever been.

We went that far east because that’s where the good water was, the place where the Gulf Stream and the Labrador Current (or what’s left of it by the time you get down to North Carolina) rub up against each other like awkward teenagers in a parked car and the resulting friction scrambles the microscopic life that provides the base of the food pyramid for every living thing in this place. That’s where the birds were hanging out, and while the diversity was merely pedestrian (I managed to get on what felt like the only two boats that *didn’t* find rare Pterodromas) it’s always a thrill to see the Cory’s Shearwaters and Black-capped Petrels and Band-rumped Storm-Petrels out here. They are the birds that the people come to see, and which I am fortunate enough to be given the opportunity to touch base with a few times every year so long as I point them out to the people on the boat. A fair price, by my reckoning.

Cory’s Shearwaters, languid and lazy, and common in the Gulf Stream in late spring.

Cory’s Shearwaters, languid and lazy, and common in the Gulf Stream in late spring.

Even in light winds, Black-capped Petrels are effortless and amazing.

Even in light winds, Black-capped Petrels are effortless and amazing.

Pomarine Jaegers, some with long tail spoons, kept us company most of the second day.

Pomarine Jaegers, some with long tail spoons, kept us company most of the second day.

Perhaps the best experience of the two days I spend offshore was not a bird, but a mammal. The depths of the North Atlantic are unknown and, in many ways, unknowable. There are creatures, large ones even, about which we know very little. A trip to the Gulf Stream offers an opportunity, however small most times, to come in contact with them. As it was when a small pod of Gervais’ Beaked Whales, small whales that look like bulked up Bottlenosed Dolphins tolerated our approach and allowed us to have a surreal experience with this mysterious marine mammal.

The best photo I could get, they were just too close!

The best photo I could get, they were just too close!

Up until the middle of last century, this species of whale was only known from the remains of beached individuals. Then a handful were photographed from the deck of the Stormy Petrel II out of Hatteras, our very own pelagic boat. Since then they’ve been seen a handful of times, the vast majority in the Gulf Stream on these birding trips. When this pod of 5 or so surrounded the boat, however, popping out of the water to show the glistening scars of the male and the subtle tiger stripes of the females, we all became one of a very small group of humans in the world to have had an experience like this with this species. It was an incredible time, and a reminder that the Gulf Stream is full of secrets.

I can’t wait to get out there again.

Leave a Comment