Happy New Year, 10,000 Birds readers and writers! Everyone is looking back on their best birds of 2019, so I thought it would be a good idea to look at a book that looks back a little further: Urban Ornithology: 150 Years of Birds in New York City, by P. A. Buckley, Walter Sedwitz, William J. Norse, and John Kieran. Because, as this book demonstrates so well, it is sometimes important to look back in order to move forward.

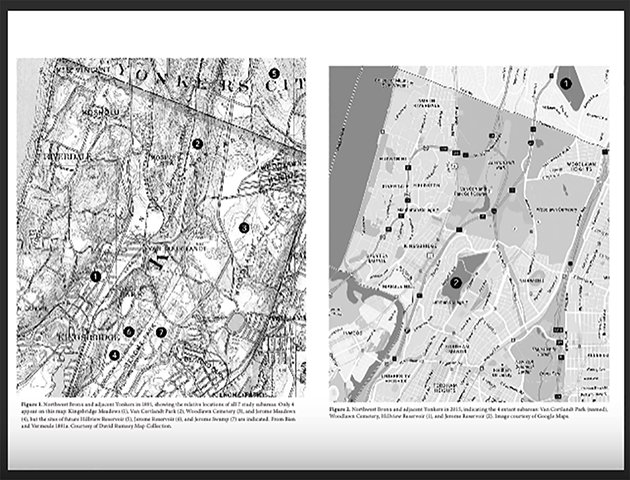

Urban Ornithology: 150 Years of Birds in New York City is a “quantitative long-term historical analysis of the migratory, winter, and breeding” birds of New York City from 1872 to roughly 2016, with a specific focus on the Bronx, and an even more specific focus on a ‘study area’ situated in northwest Bronx–Van Cortlandt Park, Woodlawn Cemetery, Jerome Reservoir, and surrounding environs (p. xii).

Two maps of the northwest Bronx and adjacent Yonkers, one from 1891 and one from 2015, pp. 2-3.

“Wait!” you’re probably saying. “Let’s back up a little. This is a book about the Bronx?!” Yeah (as we say in NYC), this book is centered on that much maligned borough of New York City–symbol of 1970’s urban decay, home of the NY Yankees, subject of Ogden Nash’s infamous two-line poem: “The Bronx/No Thonx.” This makes a lot more sense once you know a little more about the area and its history. Though the third-most densely populated county in the United States (as of the 2010 census, thank you Wikipedia), about 25% of Bronx land is open, public space. Natural areas include Pelham Bay Park, Van Cortlandt Park, Woodlawn Cemetery, New York Botanical Garden, and the Bronx Zoo. And, though I think you can argue that the Bronx Zoo, with its numerous buildings and landscaped wildlife areas is not purely ‘natural space,’ I have wonderful memories of traipsing through its wooded areas when I was a girl. (I didn’t grow up in the Bronx, but my best friend did.)

The Bronx also has a special place in birding history. The Bronx County Bird Club counted amongst its young members Allan Cruickshank and Joe Hickey, both of whom became influential naturalists, and Roger Tory Peterson, who actually did not live in the Bronx, but became good birding friends with the club’s members when he moved to New York City.*

The four authors of Urban Ornithology, only one of who is still alive, were also native New Yorkers who passionately birded the Bronx and New York City throughout much of the 20th century. This is a project that clearly spanned decades. The result is a model of how myriad resources–geographic histories and maps, ornithological books and journals, personal field notes, citizen science data, museum specimens–can be brought together to describe quantitative changes in numbers and distribution patterns of bird species in a specific location over decades, and delineate the habitat pressures and other changes that have brought about these changes, setting the stage for informed discussions on what we should do next.

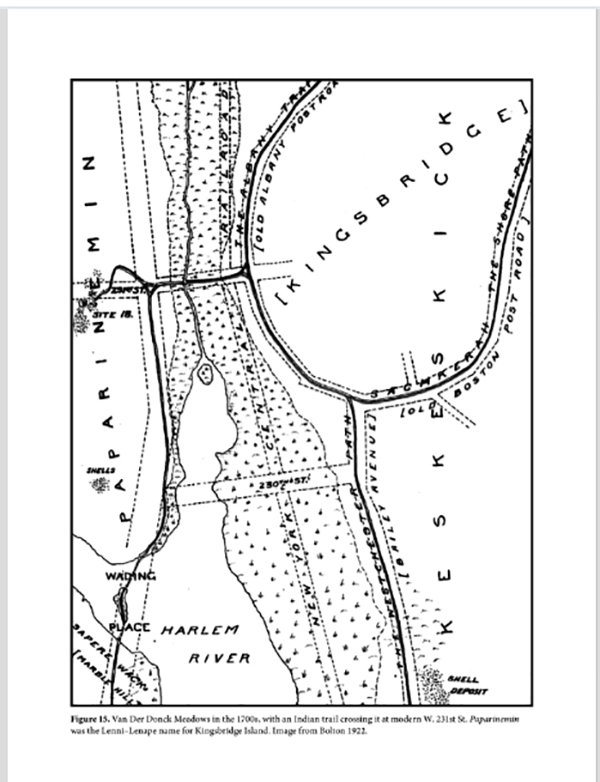

The book is divided into three parts: “Introduction,” “Avifaunal Overview,” and “Species Accounts.” There are also extensive Appendixes and Indexes, maps and tables, stories and numbers, lots of numbers. The Introduction introduces us to the Bronx ‘study area,’ its geology and geography from pre-European residency through Dutch exploration and settlement (Jacobus van Cortlandt bought land for his plantation in 1694-99), through the late 19th century, when New York State created Van Cortlandt Park, up through the advent of automobiles and parkways in the early 20th century. The geography of the northwest Bronx and changes in habitat are illustrated in detail by historic maps. The authors trace the creation of swamps, wetlands, and meadows by farmers, and then the destruction of wetlands by the building of golf courses, the loss of meadows by the construction of train tracks. Not all habitat change is due to humans; there is Chestnut Blight destroying American Chestnuts in the early 1900s, and the more recent Dutch Elm disease. Still, the authors praise more than mourn, emphasizing that the most severe changes occurred before 1955, and that some NYC infrastructure changes have actually helped area bird life.

Van Der Donck Meadows in the 1700s, with an Indian trail crossing it where W. 231st Street is now located.

The “Avifaunal Overview” reviews and discusses data sources, describes how the migration process in and over New York City, and summarizes ‘resource concerns’—factors such as the loss of keystone species, the introduction of non-native species, water quality, vandalism, illegal hunting, plant ecology–that have influenced New York City bird life. It’s a very mixed chapter. The authors’ detailed delineation of problems with the accuracy of NYC breeding bird surveys or with the limits of historical writings may test a reader’s patience. In contrast, the sections on migration, which encompass phenomena such as fallout and blow-back drift migrants, and which also offer brief anecdotes about unusual observations or observations under unusual conditions, are highly informative, even fun reading.

Most importantly, the section ends with a list of questions for future studies and recommendations for wildlife and habitat management. The recommendations will sound familiar to any birder or naturalist who wants to protect and improve her local patch: Immediately shut down cat feeding stations. Patrol and enforce wildlife-damaging violations, including the taking of endangered native plants, capturing turtles, riding ATV’s on pedestrian trails, and abandoning fishhooks. Remove Phragmites and replace it with cattails. Mow grasslands only once a year to arrest succession. And so on. However, I think they have more weight when proposed as part of a long-term environmental study like this.

Most birders will go straight to the “Species Accounts.” It’s important to note that the 301 species selected for this section are those of historical and current importance to the core study area, the northwest Bronx. These were apparently the original focus of the project, and, as explained in the Preface, the authors decided at some point to expand status coverage to the Bronx, Central and Prospect Parks, New York City, and the New York City area, which encompasses parts of Westchester County, Long Island, and New Jersey. So, Yellow Rail is included (2 dead birds and one live one are documented for the study area), but Ash-throated Flycatcher, a vagrant found in areas nearby as well as in Queens, Brooklyn, Manhattan, and Long Island, but not in the study area, is not.

In addition, many of the numbers and examples given for NYC areas beyond the Bronx represent species observed in Central Park in Manhattan and Prospect Park in Brooklyn. The authors say they want to “place Van Cortlandt Park’s avifauna in a New York City park perspective” (p.34). I suspect they also want to prove the superiority of their favorite park (which they emphasize is a natural park, not a designed one like Central and Prospect), and perhaps lay the groundwork for more resources and attract more birders. Beyond the parks, the emphasis is on status, distribution, and notable sightings in the Bronx, Manhattan (particularly northern Manhattan, an area adjacent to Van Cortland Park), and Brooklyn. Queens and Staten Island are largely overlooked.

Species order follows the AOU Checklist of North American Birds up to the 2015 supplement (so warblers come before sparrows), with a variation–certain subspecies are treated as full species (Eurasian Teal, Western Willet, Audubon’s Warblers, Red Fox Sparrow, and more).

Despite these limitations and exceptions, the status and distribution accounts are very useful. The latest edition of Bull’s Birds of New York State, the classic book on NYS bird status and distribution, came out in 1998, so the numbers and trends given here represent a 16 to 18 year jump in currency. And, the data in Urban Ornithology is supplemented with observations and comments on diverse topics–from errors in field guides that might have led to inaccurate identifications, to the authors’ search for Bobwhite on Riker’s Island in 1969, to setting the record straight on exactly when breeding Willow Flycatchers were heard in NYC (in Queens!).

Each Species Accounts (well, most of them) gives status data on (a) NYC area, current; (b) Bronx region, historical; (c) NYC area, historical; (d) Study area, historical and current; (e) Specimens; (f) Comments. The first three sections are brief, presenting a summary of the bird’s current NYC status (migrant, resident, breeder, vagrant, etc.), and historical status as described in specific ornithological writings by John Bull, Allen Cruickshank, Ludlow Griscom, E. H. Eaton, and John Kuerzi.

The Study Area sections are much more detailed, offering seasonal migration arrival and departure dates, maximum number of migrating birds, specifying evidence of potential breeding birds, CBC data, and anything else that the authors thought was significant. Historical sources are supplemented with records of sightings from Christmas Bird Counts, water bird surveys, winter bird surveys, publications of the NY Linnaean Society and NYS Ornithological Association, rare bird alerts, and hundreds of personal communications. (Surprising, or maybe not, the Queens County Bird Club’s News & Notes, which has always noted member bird sightings, was not consulted.) E-bird data up to November 2017 was used to update migrational pattern data and “for locating obscure but locally significant records that otherwise might never have seen the light of day” (p. 33).

Breeding Bird Atlas data from New York State’s two Breeding Bird Atlases is also presented in the Study Area section, with observations on species trends and changes for the local area, New York City and New York State. Putting aside the question on why city- and state-wide trends are presented under the local heading, this is extremely useful material, especially when the authors apply their informed opinions to the data. For example, on Black-crowned Night-Heron, a steadily declining breeding species, they say, “…even though they were recorded in 5 block in the Bronx during NYSBBA II in 2000-2005, we believe most did not involve breeding birds” (p. 147). The authors occasionally add mini-essays on species increases, declines, or distribution. For example, Red-bellied Woodpeckers began their colonization “without warning” on western Long Island in mid-May 1961, expanded “the invasion” in spring 1962, and then incurred a “second invasion” in spring 1969 (p. 231). Greater Scaup are the default scaup species in Long Island Sound, but after freezes, Lesser Scaup may appear in tidal creeks.

The Comments section is used to describe sightings of non-survey area species. For example, Ash-throated Flycatcher sightings are cited under the Great-crested Flycatcher Comments heading, and Swainson’s Hawk observations are cited under Broad-winged Hawk. These discussions are sometimes as lengthy as an official species account. This section is also the place for observations about the Carolina/Black-capped Chickadee contact zone, the importance of distinguishing Cliff Swallows from Cave Swallows, types of Red Crossbills identified in NYS, and other thoughts on taxonomy, banding, and identification.

Out of curiosity, I looked up several of the sightings described in Urban Ornithology, and found all the data to be accurate. There is one sighting, however, that is slightly inaccurate, and that is my own. I actually had no idea I was in this book till I stumbled over my name in one of the Appendixes, “Names of All Observers Appearing Anywhere in the Body of this Book.” I’m down as the observer of a White Pelican at the Whitestone Bridge on Dec. 16, 2012. Which is true. Only, the sighting was made at a park in Queens a mile away from the Whitestone Bridge, and the book states that the sighting was made at the other end of the bridge, in the Bronx. It’s an ironic error in a book that spends a lot of time discussing data fallacies of bird observations, and I’m probably being my usual nitpicky self by talking about it. But, I do wish the authors had added me to their extended list of people with whom they consulted so I could have set the record straight.

There are no bird illustrations in Urban Ornithology, other than Arthur Morris’s Least Bittern on the cover, but there are maps and figures in the first two chapters, and scatterplots for 43 species, illustrating Bronx/Westchester CBC data from 1924 to 2013, in the Species Accounts. There are also 38 tables in the first appendix illustrating points made in the Avifaunal Overview section. They’re worth a look at, particularly the tables giving longitudinal data and density change.

There are more appendices, reflecting the authors’ love of lists and sometimes personal anecdotes: “Scientific Names of All Organisms Mentioned in This Book Other Birds in the Species Accounts”; ” Glossary of Symbols, Abbreviations, and Terms”; “Specimans in Museum Collections from Van Cortland Park, Kingsbridge Meadows, Woodlawn Cemetery and Jerome Reservoir, and Riverdale,” and an account of how Walter Sedwitz found an Andean Gull in the Bronx in 1980. The “Literature Cited” section lists the traditional print articles, books, and maps, but doesn’t include items like data sets or rare bird alerts. The excellent Indexes to English Bird Names, Scientific Bird Names, and Subjects were organized by Jennifer W. Hanson. The bird name indexes helpfully bold page numbers of species accounts and properly list birds by the second part of their name (for example, all seven vireo species are listed under “Vireo”).

Finally, “About the Authors” gives full biographical information on the four authors. P.A. Buckley is a professional ornithologist; Walter Sedwitz was a businessman; William J. Norse was a Wall Street broker; John Kieran was a sports reporter and radio panelist. And, as I said in the beginning of this review, they spent their lives exploring the habitats and documenting the birds residing in and migrating through the Bronx, New York City and Long Island. They did breeding bird counts, breeding bird atlases, Christmas Bird Counts, and became active members of the Linnaean Society of New York and other nature organizations. Their sightings were published in Birdlore, the Auk, the Kingbird, and the Linnaean Newsletter. They wrote books and published research. I am intensely curious about how they wrote this book–when did they start, what roles did each man play, how did they deal with new sources of data, such as eBird? Clearly, members of the birding community and their families–thanked in the opening Acknowledgments section–played a strong role in getting this project done.

And for good reason. Urban Ornithology: 150 Years of Birds in New York City is not only an informative compendium and analysis of ornithological data, it’s a model for the kind of book we should be seeing more of in the future. The authors really struggled to create comparable and localized data sets from historical sources. Today, with eBird datasets, publicly available data sets from grant-funded research projects, digitized histories, computer-based maps, searchable listservs, and a wealth of other technologically-based environmental data resources, it should be much easier to pull together status and distribution data for a local, finitely defined park, wildlife refuge, even a whole city, and analyze the data within an environmental, geographic framework. And, then use that analysis to fight for our environmental lives. Or, at least, the life of our local park or neighborhood. Every New Year, I think about what new book titles will be published, what books I will be reviewing. More field guides? An identification guide for an overlooked bird family? Another big year memoir? I love reading all of the above. But, I think it’s also time to start exploring new frontiers, new types of bird books, titles that allow us to leverage our citizen science data, explore the implications of local bird distribution and status changes in conjunction with related habitat and even political and legal change, and strategize for change.

Urban Ornithology: 150 Years of Birds in New York City is a large, heavy book about birds in urban spaces (spaces reserved for nature, but still urban) and also about how to study the patterns of breeding, migration, and residency of birds in a tightly defined urban place. It will chiefly be of interest to birders who bird the Bronx and to ornithologists and researchers in related fields who plan to study the birds of New York City or do comparable studies. But, if you can afford it, this is a very handy reference book for NYC-area birders, keeping in mind that it is not a comprehensive study of avifauna status and distribution in New York City’s five boroughs. I recommended Urban Ornithology as one of the most notable publications of 2019 in my ABA Podcast discussion with Nate Swick (which I hope you all listened to) because of it’s scope, ambition and it’s intelligent use of locally-focused data to promote the visibility and needs of a specific urban spaces. It’s a different kind of book, and although it is steeped in history, it’s also an opening to creating more different kinds of birding books.

* For a history of the Bronx County Bird Club, I highly recommend this article from the 1991 issue of American Birds, a publication of Hudson River Audubon Society of Westchester.

Urban Ornithology: 150 Years of Birds in New York City

By PA Buckley, Walter Sedwitz, William J Norse, & John Kieran

Comstock Publishing Associates/Cornell Univ. Press

514 pages, 7.2 x 1.5 x 10.2 inches (and heavy)

ISBN-10: 1501719610; ISBN-13: 978-1501719615

$75 (hardcover); $36.99 (ebook); $29.22 (Kindle); discounts from the usual suspects

Wonderful piece, Donna! And nice to read something about da Bronx for a change. 🙂 If I were still living in Westchester I would definitely pick up that book!