It was a cold afternoon in Maine, and I was looking at the Steller’s Sea-Eagle perched on a tall coniferous tree across Boothbay Harbor, having arrived at the harbor area seven minutes earlier (I know! Thank you, goddess of birding luck and text group people).* My inner self felt stuck in an area between disbelief and total joy and the voices near me were echoing this state of mind: “Oh My God,” “I never thought I would see this bird,” “Look at that bill!” “Now I don’t have to bird Hokkaido in February,” “How the f*** did it get here?” This last question, leaving aside the expletive, is the question most apt to be asked when any vagrant bird is found, by locals astounded by the sudden influx of traffic and people with binoculars and expensive cameras, by new birders still figuring out migration and seasonality, by New York Times reporters, even by experienced birders, some of whom spend thousands of dollars to chase “mega” vagrants. It’s interesting to see how it’s answered, sometimes with terms like reverse migration and magnetic field, sometimes with a monolog about climate change, sometimes with the comment “It’s a bird. It has wings. It can fly.”

Steller’s Sea-Eagle, Boothbay Harbor, January 24, 2022 Copyright © 2022 Donna L. Schulman [not from the book!]

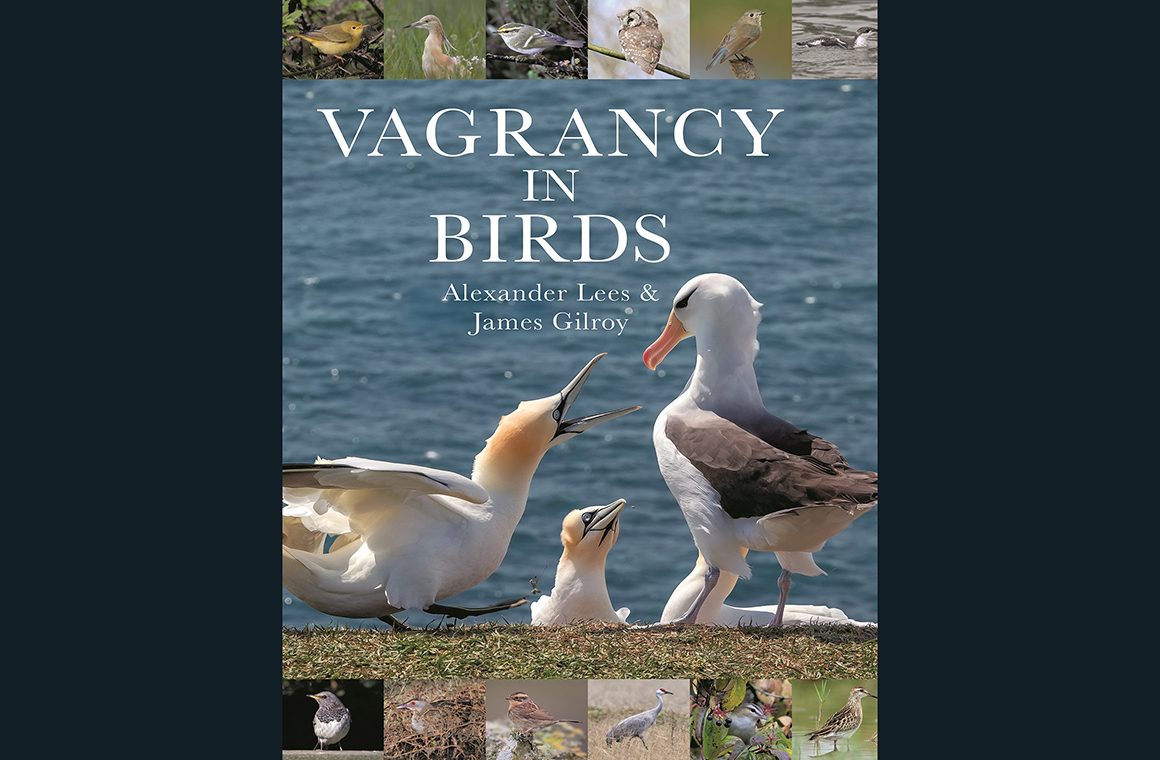

“How did that bird get here?” and its companion question, “Why is this bird here?” are the big questions at the heart of Vagrancy in Birds by Alexander Lees and James Gilroy, an impressive, fascinating book about what ornithologists and wildlife biologists have found out about avian vagrancy so far and their theories explaining this phenomenon. It also summarizes the vagrancy status of every bird family in the whole wide world, which makes it fun to read as well as superbly educational.

Vagrancy in Birds is organized into two major parts: (1) A detailed, 62-page synthesis of research and theory and (2) “Family Accounts,” 259 pages covering bird families from Struthionidae/Ostriches) to Thraupidae/Tanagers and allies (Clements is the taxonomic authority). An introductory “Scope of the Book” sets out the authors’ goals and defines key concepts; a concluding “Avian Vagrancy in an Era of Global Change” gives us some meaty issues to thing about; and the expected back-of-the-book sections add scientific backbone and reader usability–References and indexes to general subjects and species. The book is richly illustrated with contributions from a group of birders/photographers who were fortunate to see and document many of the vagrants covered.

The authors aim “for the first time [to] systematically explore the taxonomic and geographic patterns of extralimital avian occurrence globally and try to synthesize what we know about the processes that underpin these occurrences, based on the latest scientific discoveries” (p. 7). Of course, the first step is to define what is a ‘vagrant bird,’ a discussion I really appreciated since I’ve noticed that we (as in birders in general) tend to bandy the term about interchangeably with ‘accidental,’ ‘exotic,’ ‘scarce migrant,’ and ‘MEGA MEGA.’ The authors point out that defining vagrant as a bird outside its normal range just won’t do since ranges are not fixed and there is a gray line between the furthest edges of the migration route of a highly migratory bird and points beyond. They define geographic range as encompassing “something like 99.99 per cent of individuals of a species at a given time” and a vagrant bird as a bird that shows up outside of this range (p. 7). But it’s a very fluid definition, as the book makes very clear. One of the themes and scientific points that pops up over and over again is the role vagrancy plays in establishing new migration routes and changes in species distribution, particularly in response to the changes in weather patterns and other ecological factors wrought by climate change. Today’s vagrant could be tomorrow’s resident, a change that is visibly happening with, for example, the Clay-colored Thrush in southern Texas.

Copyright © 2022 Alexander Lees and James Gilroy

The reasons for vagrancy, formerly simply assumed to be crazy weather or a bird with a screw loose, are increasingly being researched in a number of ways, helped by improvements in technology, the crowdsourcing of huge datasets like eBird, and a recognition that vagrant birds are more than a twitcher’s delight. Less and Gilroy sort through the exogenous (external) and endogenous (internal) factors thought to cause vagrancy and the scientific experiments that have sought to prove their significance with patience and plain language as well as charts and photographs. There are many more factors than I imagined: compass errors, wind drift, overshooting, extreme weather and irruptions, natural dispersal, and human-driven vagrancy.

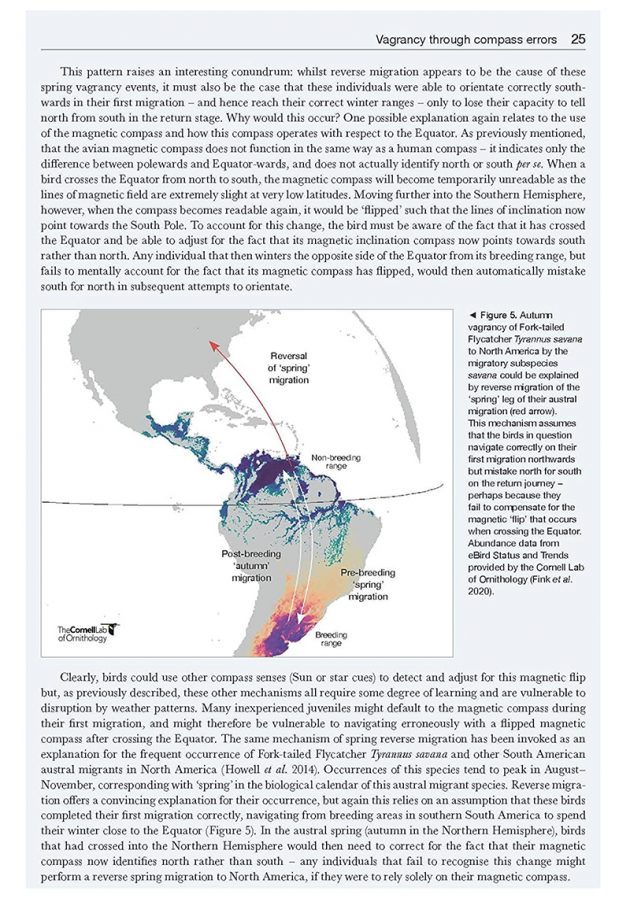

The chapter on compass errors will probably be the most popular amongst birders who love to discuss reversal and mirror-image migration routes. It involves figuring out how birds know how to migrate in the first place (highly migratory birds are most prone to vagrancy)–genetic coding? internal compasses tied to the earth’s magnetic fields? other compass senses like the stars?–and how an error may be made and how that error may become a pattern. This chapter also covers vagrancy in social migrants, and why vagrancy is common in ‘obligate social navigators’ like geese and cranes, a thought which got me thinking of all the times I’ve searched for one Barnacle Goose amidst hundreds of Canada Geese. Next time, I’ll know why. Some birders may want to carefully read the chapter on human-driven vagrancy, which takes up the question of ship-assisted vagrancy. Is the ship-assisted vagrant a ‘true’ vagrant? The authors’ answer is more complicated than you may think, involving the complexity of assessing a bird’s overwater flight capacity, and no definitive answer is given.

The complexity of the vagrancy process is an underlying theme of the book, the authors continually explaining how one factor may tie into another and how research experiments have tried to untangle all the causative knots. It’s not always easy reading. The diverse range of vagrancy factors dips into related sciences–earth science and magnetic fields, geography and climate, dispersion and evolution–that may not be familiar to readers with little science background. The world-wide perspective means that the authors are often discussing birds and regions unfamiliar to the North American reader. This leads to googling birds and countries and then day dreaming about visiting these countries and seeing those birds, making for a rather time consuming reading period. I appreciate a book that challenges me; I adore a book that stimulates appreciation for the world’s biodiversity and nature’s interconnecting parts.

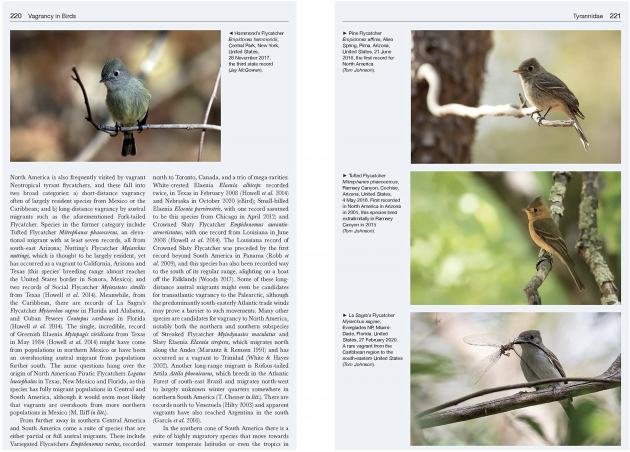

The Family Accounts are the fun part of the book. I so very much enjoyed browsing through it, reliving some of my favorite vagrant birds: the Tupper Lake (NY) Ross’s Gull; the Cedar Beach (NY) Corncrake; the Pacific-slope Flycatcher and Hammond’s Flycatchers that showed up in Central Park in 2015 and 2017 respectively (there’s even a photo of the poo Nathan Goldberg collected to analyze for DNA so the silent Pacific-slope could be identified!); and a bird that I didn’t see but feel I know well, the Plain-capped Starthroat that spent a summer in my friends’ Portal, Arizona backyard. Don’t worry. There’s a lot in this book to digest and savor, even if you’re not a twitcher. It reminds me a lot of Rare Birds of North America, the 2014 book by Steve N. G. Howell, Ian Lewington, and Will Russell on distribution and identification of vagrants. Rare Birds was a major source for this book, but Vagrant Birds has a more scientific approach, more synthesis of research, less –actually no–field identification.

Copyright © 2022 Alexander Lees and James Gilroy, text; Copyright © 2022 Jay McGowan photo p. 220; Copyright © 2022 Tom Johnson photos p. 221

The Family Accounts are also a deeply informational, documented source of information for researchers. The accounts cover vagrancy patterns for the family as a whole, reasons for vagrancy, documented examples of vagrancy for specific species and reasons that might account for those incidents. Length varies, with high vagrancy family accounts like Anatidae (Swans, Geese and Ducks) and Laridae (Gulls, Terns, Skimmer) seven to ten pages long and non-migratory, sedentary families like Indicatoridae (Honeyguides) and Grallariidae (Antpittas), just a brief paragraph, sometimes just one or two sentences. The writing and organization very nicely straddle the line between scientific writing and layperson’s language, with both the scientific name coming first in each family section heading (as reflected in my writing here) and the common name written first in the text and photo captions. Vagrancy trends and sightings are documented throughout the text, references to the over 700 reports, articles, and books listed in the References section.

As in the first part, the accounts are illustrated with many photographs, some of specific vagrant birds described in the text, some examples of species cited for their vagrant tendencies. The photos are all of excellent quality, not an easy feat when you’re photographing in the field under conditions that are usually far from optimal. The authors seem to have recruited most of the photos through eBird reports and many, though not all, of the photographers are listed in the front Acknowledgments section (hopefully Cameron Rutt will be added in a later edition). Many of the North American vagrant photographs are by Tom Johnson, Jay McGowan, Cameron Rutt, and Ian Davies, familiar names in our small birding world. I also appreciated the occasional photo of a birder (or birders or photographers) photographing vagrants, including the well-circulated one of hundreds of photographers in Beijing gathering in a semi-circle to photograph a Japanese Robin in November 2012.

I am in awe of the amount of work authors Alexander Lees and James Gilroy clearly put into this volume. They are British ornithologists who have spent time working in the United States. Alexander Lees is a Senior Lecturer in Biodiversity at Manchester Metropolitan University, a Lab Associate of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and the author of numerous scientific papers on Amazonian ecosystems and biodiversity, where he has been doing research for 17 years. He’s a birder and a bird photographer who spent some time in his earlier years guiding film crews and birders in Brazil. James Gilroy is a Lecturer in Ecology at the University of East Anglia, a past member of the Lockwood Lab at Rutgers University and the Norwegian University of Life Sciences in Oslo, author and co-author of numerous articles on biodiversity conservation, agricultural policy, and land use change. He is also, according to his Bloomsbury Publishers’ bio, “an obsessive birder and vagrant-hunter (when time allows!). The two men have co-authored several previous articles on avian vagrancy. They also appear to have been part of an informal, crazy birding group in the early years of the 21st century called “punkbirder” that possibly fueled their obsession and collaboration on this topic. (Never underestimate the reach of the Internet, the website you put up 20 years ago might still be there.)

* If you’re unfamiliar with the weird and wonderful peregrinations of the Steller’s Sea-Eagle first seen in Denali, Alaska and then in Texas, Gaspé Peninsula, Nova Scotia, Massachusetts and Maine, Nick Lund’s article for National Audubon nicely sums it up to early January (before Boothbay Harbor) and the webinar with Doug Hitchcox and Nick Lund for Maine Audubon gives the full story, complete with much background information.

Thanks to Princeton University Press for a reviewer’s copy of this book and permission to reproduce pages and thanks to Jay McGowan and Tom Johnson for permission to use their photographs on those pages.

Vagrancy in Birds

Alexander Lees & James Gilroy

Princeton Univ. Press, Feb. 2022 (available in Europe from Helm/Bloombury)

400p. 360 photos & illustrations; 2.8 pounds; 6 x 1 x 9 in.

ISBN-10 : 0691224889; ISBN-13 : 978-0691224886

$35 (discounts from the usual sources)

Great book I agree, but OMG the font size….. I feel like I need to invest in a magnifying glass it is soooo small. It is an absolute slog to get through at that size.