Peripatetic ornithologist Nick Sly has long been a friend of the blog here and has contributed such classics as Green-rumped Parrotlets from Egg to Adult and Forpus passerinus and the Ornithologists of Masaguaral. We’re always interested in what he’s up to and pleased that his research and our collective interest in cool birds can come together in such an opportune manner. Please read and then vote for either Nick or Maria’s research!

Would you support research on birds with just a click on Facebook? My labmate Maria Stager and I have entered a contest for a $10,000 research grant from Endnote. To win, we need your votes!

Maria and I, first-year graduate students in Zac Cheviron’s lab at the University of Illinois, Urbana-

Champaign, are studying the genetic basis of morphological and physiological adaptations in birds. Basically, we want to learn the molecular mechanics of how birds function and evolve. This type of work is new and exciting, but also expensive! We both have budgets of at least $10,000 required to complete the genetic portions of our graduate research. Research funding sources are always highly competitive, there are very few big-budget grants available to graduate students, and it is quite difficult for grad students to compile enough grant money to fully fund their research. Winning the Endnote contest would be a huge boon for our projects, taking us much closer to full funding!

The competition works by voting on Endnote’s X6 Launchpad Facebook Page. The proposals go through a two week voting period (already half-over, voting ends April 14th!!), after which, the six proposals with the highest votes move on to a grant review panel that chooses the winning proposal based on scientific merit. Maria and I have each written a brief summary of our research proposals below, and you can click the links to read our full scientific proposals on the Endnote Facebook page. For the competition, you are only allowed to cast one vote, so we simply ask that you consider our projects, pick the one you like best, and vote! We represent the only two bird proposals in the competition (you can view the other proposals here), so a vote for either of us is a vote for bird research, and a vote for the Cheviron Lab! Thanks for your support!

Maria’s Project

In light of spring’s recent arrival, do you ever find yourself wondering how some species are able to withstand freezing, wintery days and yet still thrive in summer’s heat? While birds do have fat and feathers, they also rely on their pectoral muscles to generate heat. But how do they adjust this physiology with the changing seasons? What are the mechanisms by which this occurs? And what cues do they use to do so? My proposal, “An integrative understanding of phenotypic flexibility”, aims to answer these questions by investigating the molecular mechanisms underlying seasonal changes in metabolic performance of a common songbird, the Dark-eyed Junco.

A junco thermoregulating in a snow bank

A junco thermoregulating in a snow bank

Juncos breed in much of the U.S. and Canada but they are also a frequent feeder bird during the winter months. They are able to succeed in these varied climate conditions by integrating environmental signals, which induce changes in gene expression and, in turn, physiological responses that allow them to ramp up (or scale down) their metabolisms. My work explores the potential effects of two environmental variables—day length and temperature—on junco metabolism and metabolic gene expression in order to better understand how wild birds accomplish these awesome feats!

A junco using a warm wool glove to thermoregulate

A junco using a warm wool glove to thermoregulate

My Project

My research proposal “Towards a mechanistic understanding of feather colors”, investigates the genetic basis for color patterns in birds. I have always been fascinated by the tremendous diversity in color and pattern in the bird world, and I want to figure out how it all works. We know the basics – most feather colors are produced by two types of pigments, melanins and carotenoids, and by structural colors (feather color is reviewed in this 10,000 Birds post) – however, the actual molecular mechanics are poorly known. We don’t really know how pigments and structural colors are laid down into growing feathers, nor do we know how birds regulate these processes to create patterns on feathers, and create different colored patches across the body. This kind of detailed genetic and developmental work has traditionally relied on model species in the lab (aka chickens). However, as a birder, I felt compelled to work on real birds, and searched for a wild study system, especially a Neotropical species, that would suite my needs.

A typical Neotropical bird – a Royal Flycatcher caught on a scouting trip in Panama. Seriously, who would want to work on chickens after seeing that? Just look at that thing!

A typical Neotropical bird – a Royal Flycatcher caught on a scouting trip in Panama. Seriously, who would want to work on chickens after seeing that? Just look at that thing!

As it turns out, there is a great system in Panama for studying the genetics of color. Manakins in the genus Manacus display on leks, where males flash brightly colored collars and long tufted beards as they dance around females in a court on the forest floor. Males in this genus all have nearly identical patterns, but differently colored collars and beards – they are aptly named the White-collared (M. candei), Golden-collared (M. vitellinus), and Orange-collared (M. aurantiiacus) Manakins. Two species, White- and Golden-, form a hybrid zone where their ranges meet in Bocas del Toro, Panama. Previous studies of sexual selection on collar color, as well as the genetics of the hybrid zone, have reached an interesting conclusion – females of both species in the hybrid zone prefer yellow over white males, so the yellow collar color of the Golden-collared is spreading into the range of White-collared.

Thus, birds in the hybrid zone have the morphology and genetic background of White-collared Manakin, but the plumage colors of Golden-collared. This makes it an ideal case for me – first, hybridization mixes up the genomes, making it easier to statistically test for genes linked to particular traits, and second, the yellow color trait now exists in the genetic background of the white-collared species, where it should be much easier to find when compared to the genomes of the two parent species. My research proposal is to catch male manakins of the two species and the hybrids, pluck growing feathers, and measure gene expression levels to figure out which genes are controlling the different feather colors.

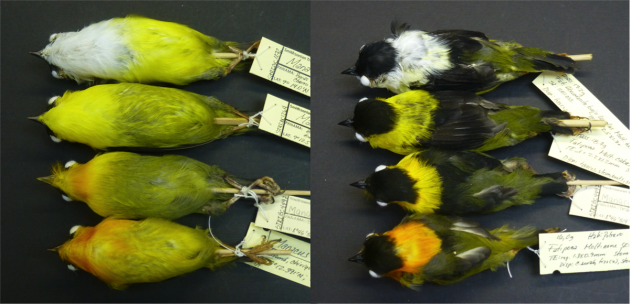

From top: White-collared Manakin, hybrid Golden-collared x White-collared Manakin, Golden-collared Manakin, and Orange-collared Manakin

From top: White-collared Manakin, hybrid Golden-collared x White-collared Manakin, Golden-collared Manakin, and Orange-collared Manakin

To vote for your favorite project, click through to the specific project proposal in the links above and look for the Vote symbol in the upper right corner. It may ask to add Endnote as an app on your Facebook page – I know many have an aversion to apps on Facebook (myself included) but it’s for a good cause.

Thanks for your support!

I’ve got to go with Maria’s project since it involves Juncos, which are my constant companions all winter. And today there are scores of them feeding in my yard atop this beautiful April snowfall.

Hey Nick, would it be possible to find the genetic basis of female mate preference?

David – It’s certainly possible, although that area isn’t quite my specialty. It’s difficult and not quite straightforward to find the genetic basis for a behavioral trait like mate preference, but it can be done in ideal situations. The behavioral preference has to have a strong genetic component and there has to be a lot of genomic resources available. A quick search of the literature reveals a lot of work from model laboratory organisms like fruit flies and fish, but little detailed work for wild birds. I doubt it would be possible, at this stage, to do this with Manakins. Here’s an review I found for the basis of mate preference in fruit flies: http://www.hindawi.com/journals/ijeb/2012/328392/

We did it! Maria Stager and I have both advanced to the next round thanks to your votes! Our proposals will now be judged by a grant review panel, and the winner will be announced in May. Thanks for all your support!!! And special thanks to Mike and Corey for helping to spread the word here and on Facebook!

Whoo-hoo! Good stuff, Nick (and Maria)!