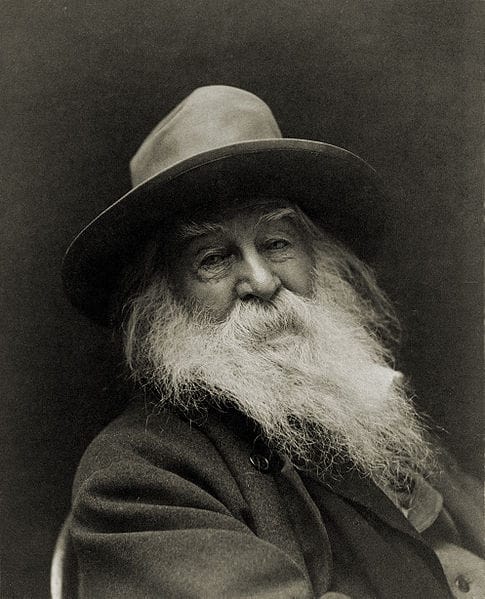

In the final version of Walt Whitman’s famed poetry collection Leaves of Grass – the “Deathbed Edition” – there is a poem  dedicated to the Magnificent Frigatebird, or, as Whitman knew it, the Man-of-War-Bird. “To the Man-of-War-Bird” was actually first published nearly a quarter-century earlier in the British literary paper, The Athenaeum, and was reprinted in 1878 as “Thou Who Hast Slept All Night Upon the Storm” in Progress, a Philadelphia-based literary journal. When Whitman included it in Leaves of Grass he put in the section called “Sea Drift” which featured poems related to the ocean.

dedicated to the Magnificent Frigatebird, or, as Whitman knew it, the Man-of-War-Bird. “To the Man-of-War-Bird” was actually first published nearly a quarter-century earlier in the British literary paper, The Athenaeum, and was reprinted in 1878 as “Thou Who Hast Slept All Night Upon the Storm” in Progress, a Philadelphia-based literary journal. When Whitman included it in Leaves of Grass he put in the section called “Sea Drift” which featured poems related to the ocean.

The poem is literally addressed to a Magnificent Frigatebird from a shipbound Whitman after a long and stormy night. If you have ever been at sea in rough weather you might have some inkling of how Whitman felt after spending all night in a sailing ship while a storm raged (but, remember, this was before the days of engines, GPS systems, and ship-to-shore radio). To a weary Whitman, relieved at having survived the night to find clear skies, the Man-of-War-Bird would seem a marvel, floating through the air none the worse for wear, and it is no surprise that a man with a mind as imaginative as Whitman’s would have wondered where the bird was all night and how it survived the storm. It is even less of a surprise that a man as poetic as Whitman would have put pen to paper to express his thoughts.

To the Man-of-War-Bird

Thou who hast slept all night upon the storm,

Waking renew’d on thy prodigious pinions,

(Burst the wild storm? above it thou ascended’st,

And rested on the sky, thy slave that cradled thee,)

Now a blue point, far, far in heaven floating,

As to the light emerging here on deck I watch thee,

(Myself a speck, a point on the world’s floating vast.)Far, far at sea,

After the night’s fierce drifts have strewn the shore with wrecks,

With re-appearing day as now so happy and serene,

The rosy and elastic dawn, the flashing sun,

The limpid spread of air cerulean,

Thou also re-appearest.Thou born to match the gale, (thou art all wings,)

To cope with heaven and earth and sea and hurricane,

Thou ship of air that never furl’st thy sails,

Days, even weeks untired and onward, through spaces, realms gyrating,

At dusk that lookist on Senegal, at morn America,

That sport’st amid the lightning-flash and thunder-cloud,

In them, in thy experiences, had’st thou my soul,

What joys! what joys were thine!

The Man-of-War-Bird has so mastered flight that the sky is its “slave” and Whitman has been reduced to a “speck” far, far, beneath the bird. Instead of feeling insignificant in an environment to which the bird is excellently adapted Whitman is exhilarated by the idea of what the bird experiences. He does not sink to anthropomorphism though, and recognizes that to the bird its experiences are nothing special. But if the bird had Whitman’s “soul, / What joys! what joys” the bird would experience.

Though Whitman is unable to physically master the power of flight his flight of fancy does enable him to imagine what it would be like to “sport’st amid the lightning-flash and thunder cloud” and that allows him to appreciate the bird’s “prodigious pinions” and share that appreciation with his readers even over one hundred years after his death. And, really, isn’t that at least as impressive as being able to out fly a storm?

…

If you liked this post and would like to browse the entire archive of poetry posts on 10,000 Birds please check out our Bird Poems page.

…

Way to go, Cory! I enjoyed your post very much.

Poetry and birds are two of my interests.

Thank you.

carolyn

THIS POEM IS VERY BEAUTIFUL.