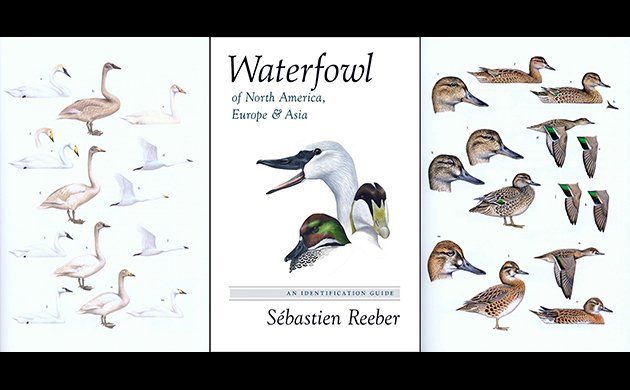

Waterfowl of North America, Europe, and Asia: An Identification Guide by Sébastien Reeber is an exhaustively comprehensive reference book that is sure to bring joy to the heart of every birder who slowly scopes through the hundreds of ducks in the local marsh or bay and eventually, after an hour or so, looks up, smiles, and says, “I have a Eurasian Teal.” Or, a Tufted Duck or Cackling Goose. Or, for an increasing number of birders, an “interesting hybrid.”

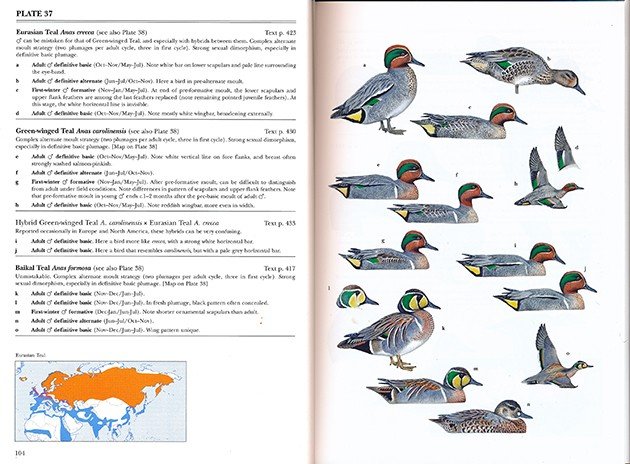

Plate 37, Eurasian, Green-winged, and Baikal Teal

Ducks, swans, and geese may initially appear easy to identify. I started out my birding life sitting on Benches 2 and 7 at the Jamaica Bay NWR West Pond, my Peterson’s in my lap, studying Green-winged Teal, Northern Shovelers, and the occasional Pintail. So much simpler than pinning down those warblers! But, as with many avian families, the more you look, the more complicated it gets. There are the females, so many so brown. And, that thing called plumage. Which is related to that other thing, called molt. And, when you finally think you have that all down pat, there is the goose that just might be Pink-footed. Unless it’s a hybrid Pink-footed/Barnacle? And, the whole question of subspecies, which in the Northeast tends to focus on the Cackling Goose, but which I’m sure is a topic of fascination with other waterfowl species in all other parts of the world.

Published by Princeton University Press in early 2016, Waterfowl of North America, Europe, and Asia (I’m going to use this shortened title for the rest of the review), covers 83 species of Anseriformes–ducks, geese, and swans–of, yes, Europe, Asia and North America. (The publicity material says 84 species, but I counted and recounted, and I only see 83. Looking further, the book itself says ‘83’ in the introduction. A minor item, but I like to get these things right.) It is the English-language version of Canards, Cygnes et Oies d’Europe, d’Asie et d’Amérique du Nord, published in late 2015 by Delachaux and Niesté. It has also been published in Great Britain by Bloomsbury Publishing under the title Wildfowl of Europe, Asian, and North America, which explains why the English translation has British spelling conventions.

The book is organized into four major parts: (1) Introductory chapters, (2) Colour Plates, (3) Species Accounts, and (4) back-of-the book Reference and Index sections. It’s heavily illustrated with both drawings (72 Colour Plates, 920 drawings) and photographs (over 650), and employs extensive references to and from each section, which makes research relatively easy.

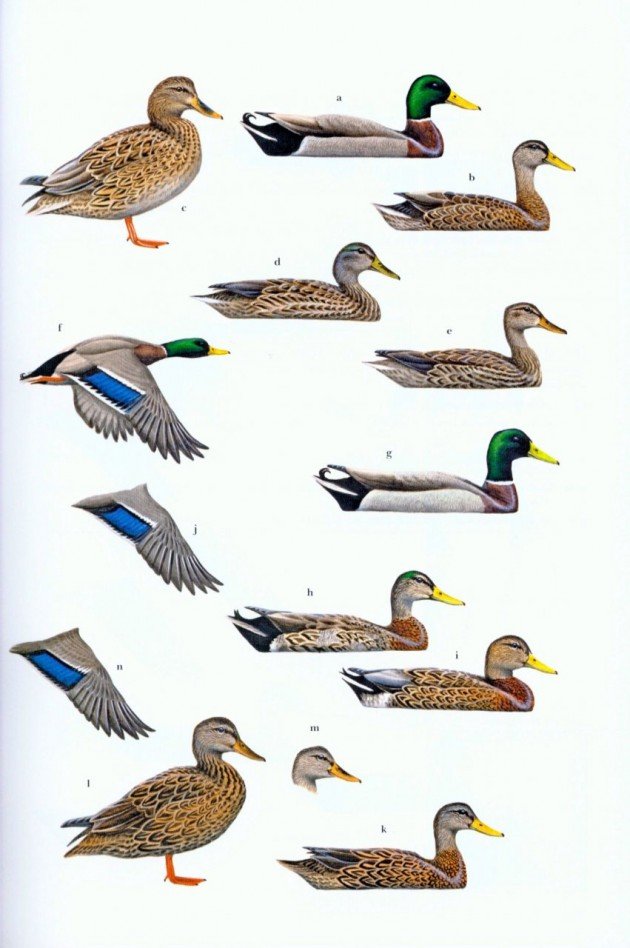

Plate 29, Mallard and Mexican Duck

This is a hefty book, a little larger than a standard hardcover, but long (656 pages), and the good quality paper makes it heavy. It’s a guide made for the desk or the car, not the field. And, it is a guide based on scholarship as well as field work (author Reeber has monitored the birds of the Lac of Grand-Lieu, France, for the National Society for Nature Protection (SNPN) since 1994). Each Species Account is heavily footnoted and the lengthy Reference section includes hundreds of articles from ornithological journals and proceedings. (This is the first bird guide I’ve reviewed that has utilized and credited a Flickr group, the Bird Hybirds Flickr Forum. It’s good to see acknowledgement of social media as a knowledge source.)

Introductory chapters are the expected– How to Use This Book, Taxonomy and Systematics, Avian Topography, Moult and Plumages, Ageing and Sexing, and Hybridisation. As befits a book about waterfowl, a lot of attention is given to molt and plumage, with extensive discussion on how and when these birds molt and an extended definition of the revised Humprey-Parkes molt classification system. Reeber also goes into more detail than any other identification guides I’ve reviewed on specific features to observe for aging and sexing of Anseriformes. This is material that some birders will gobble up and that others may find intimidating. I belong in the latter category, but I keep reading it, because I know there is a day when it will all make sense. Probably a duck calendar and a map of migratory routes would help.

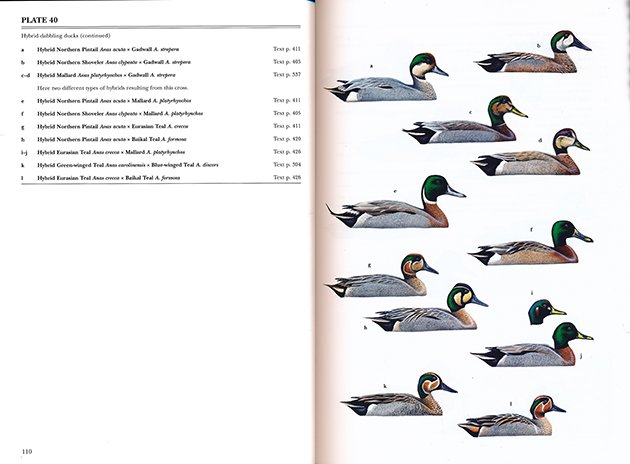

Plate 40: Hybrid dabbling ducks (a continuation of Plate 39)

There is one topic that this guide covers better and more thoroughly than any identification guide I’ve reviewed–Hybridization (or, hybridisation in British spelling). I don’t know if ducks and geese are more likely to hybridize than other families (and Reeber discusses this question, pointing out that it is easier to observe Anseriformes hybrids than, let’s say, flycatcher hybrids, and also that duck and geese species are closer in terms of evolutionary development than species in other families and thus more likely to hybridize), but I do know that questions about duck and goose hybrids are cropping up repeatedly on my birding listservs and social media sites. And, it is a word that apparently strikes fear in the hearts of even experienced birders (Armistead and Sullivan refer to it as “the dreaded H word in Better Birding), probably because there is very little information out there about more than a few common hybrids.

Reeber discusses hybridization extensively in the introduction–hybrids and backcrosses, identification challenges, conservation issues–and offers 24 photographs to illustrate common and interesting combinations. Hybrids are also included in the Colour Plates section, and in the Species Accounts, and, in case you are confused, there is a Hybrids Index in the back. The Species Accounts describe each hybrid in detail, giving degree of rarity and whether it tends to occur in the wild or in captivity, description of structure and plumage and other relevant features, and the specific influences of each parent species. A grand total of 107 hybrids are covered here, including drawings and photographs. The possibilities are seemingless endless: Barrow’s Goldeneye x Hooded Merganser, Canvasback x Ring-necked Duck, Northern Shoveler x Garganey.

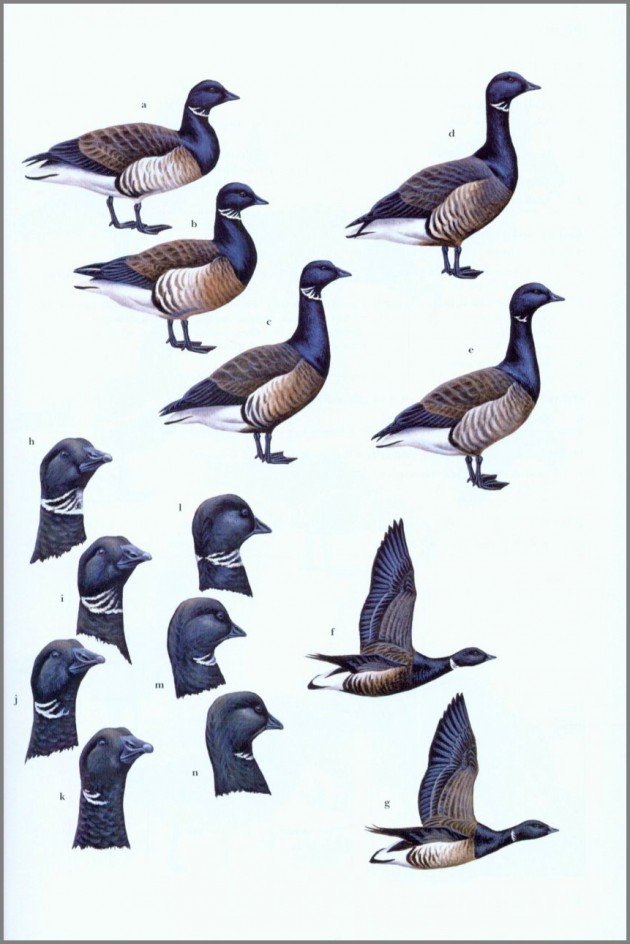

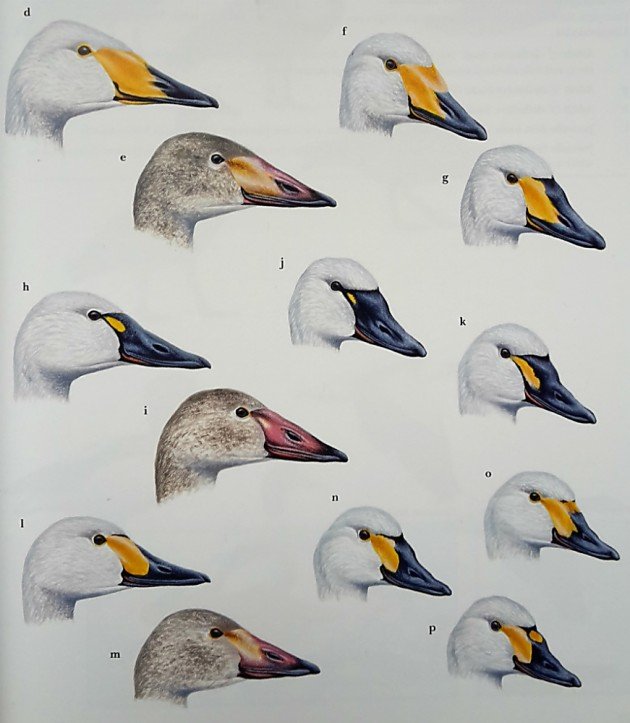

The “Colour Plates” section is a quick identification guide, presenting text on the left and meticulous drawings on the right. (I assume the artwork is by Reeber, no other accreditation is given.) Each species is shown in each molt phase–male and female, full-form and flying, wing close-ups for some. close-ups of bills for others. Two or more species are presented on each plate in many cases—Canada Goose and Cackling Goose, Trumpeter, Whooper, and Tundra Swan, Blue-wing Teal and Cinnamon Teal, and the images often spill over to two or more plate spreads. The image above is of Brant, one of the species that gets its own plate, actually two. Plate 14 includes close-ups of the head and neck, showing how the white collar varies between subspecies.

Left-hand page text for the Colour Plates gives the basics–common name, scientific name, a very brief description that often concentrates on molt strategy, degree of sexual dimorphism, references to additional plates and to Account Species text. It then lists the images on the plate by subspecies (if there are any) and molt, with descriptive notes. This section also includes range maps, indicating range by breeding season, wintering season, and residence year-round. The maps cover established ranges, but at least in one case–Egyptian Goose–they don’t cover areas in which the bird has begun to establish a new foothold (Florida).

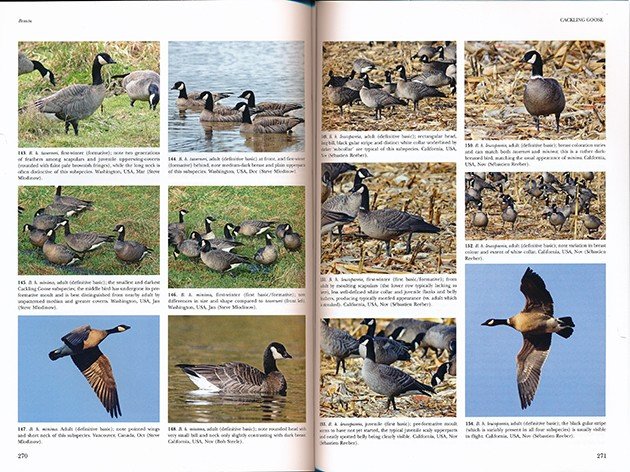

Cackling Goose, 2 of the 3 pages of photos

The extensive Species Accounts take up two-thirds of the book and constitute possibly the most complete, up-to-date coverage in print of ducks, geese, and swans residing or migrating in North America, Europe, and Asia. For each species, we get common and scientific names (including all versions of common names, such as Goosander/Common Merganser), page references to the corresponding Colour Plates, extended treatment of taxonomy and current taxonomic conflicts; identification risks (can the species be confused with others?); description of plumage for each sex and age group, including, for some, drawings of wing tips; geographic variation with individual treatment of subspecies; measurements and mass for each subspecies; voice; molt strategy; hybridization, with individual descriptions of each type of hybrid; habitat and life cycle; range and population of each subspecies, including conservation concerns; frequency of species being kept in captivity (an important consideration for determining origin or species being seen in the wild in an unusual place); and bibliographic references.

As I said above, the text is carefully footnoted; data reflects recent surveys up to 2014, and the scholarly articles up to 2012. The text is highly scientific, with little room for creativity. I think more could have been written about vocalizations. For some species accounts, you can find more information on the Cornell Lab of O All About Birds pages (Mallard, for example). At the very least, references could have been made to online recordings, so the reader could know as much about how a duck, goose, or swan sounds as how it looks. Habit and Life Cycle sections are concentrated, focusing more on identification elements than on nesting and mating habits, a necessary decision for a guide of this scope.

Each Species Account includes photographs showing key identification features and comparing similar species. This is a nice complement to the more formalized art of the Colour Plates, showing the ducks, geese, and swans as they look in “real life,” where molts can be variable and legs can be muddy. Hybrid photos can be found here, though most are in the introductory Hybridisation section. I particularly like the three head shots of “possible” Snow Geese X Ross’s Geese. It’s nice to know that even the experts can’t be sure.

The photos are by a number of photographers, including Reeber; the overall quality is fair to excellent, with most somewhere in-between. The images are clearly meant to illustrate specific molts and identification features, not to show off photographic skill. Though, let’s face it, it’s hard not to take a beautiful photo of a Harlequin Duck or a Redhead. Or, even a female King Eider, with its sophisticated lines and complex brown patterning. There are a lot of beautiful ducks (and swans, and even some geese) out there.

Waterfowl of North America, Europe, and Asia: An Identification Guide is a serious book for serious birders. It is not a cheap book, it is a book whose use will soon justify the cost, especially if you are a fan of Anseriformes hybrids. It may even make duck identification as easy as it once was at Jamaica Bay, Bench 2.

Plate 20, Trumpeter, Whooper, Tundra Swans

Waterfowl of North America, Europe, and Asia: An Identification Guide

By Sébastien Reeber

Princeton University Press, March 2016

Hardcover, $45 (discounts available from the usual suspects)

72 color plates. 650+ color photos. 85 maps

ISBN-10: 0691162662; ISBN-13: 978-0691162669

Also available as Canards, Cygnes et Oies d’Europe, d’Asie et d’Amérique du Nord from Delachaux and Niesté and as Wildfowl of Europe, Asia and North America, Helm Identification Guide series, Bloombury Publishing.

Thank you for the comprehensive and interesting review. I’m in the market for this type of guide so it was very helpful!

Looks like a good book, pity it’s only for my northern birding brothers and sisters.

Karen–That’s exactly what I’m going for! I want birders to get an idea if the book is a good fit.

Duncan–This leaves room for you to write the comprehensive guide to waterfowl–hey! all birds–of the Southern hemisphere.

Awesome Information