Assuming you have a passing interest in wildlife, or at the least you know someone that does, and chances are in the last week or so you’ve become aware that some lady from America shot a lion. I’ve certainly seen the story plenty in my Facebook news feed, and were I more of a Twitter user I am sure I would have seen it there too. It may even have been mentioned in Google+, although it is unlikely anyone noticed. 99% of the commentary I have seen has been angry bordering on outright hostile, the few exceptions mostly being the kind of right wing “news” sites that love nothing more than tweaking a tree-hugging liberal like myself. You can get a pretty good idea of the case for the prosecution by reading my good friend Charlie’s take on the story. Clearly, in the face of near universal condemnation from the internet masses, there is only one course of action for me. I have to defend her and even what she did. I’m glad she shot that lion, and I think you should shoot a lion too (Only where valid, terms and conditions apply. The views expressed here are not necessarily those of the rest of 10,000 Birds. Qualifying statements to follow).

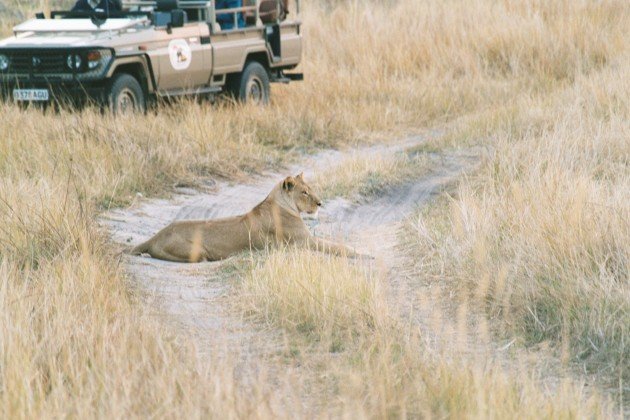

This Lion should not be shot, as it is a protected reserve that forbids shooting.

This Lion should not be shot, as it is a protected reserve that forbids shooting.

I’m not just saying this to be an annoying gadfly on the backside of the birding and general wildlife community, although this is certainly a fringe benefit. I’m not even trolling (much). Hunters go to Africa to shoot lions, and this is without question a good thing; for birds, for ecosystems, and for lions in general! Not, I’ll admit, the specific lion in question, but that’s acceptable if the net result is better for lions in general. At least, and this is the important qualifier, if you’re taking the conservation perspective.

I’ve discussed this, at length, before. The interests of those working for conservation and those working for animal rights and animal welfare don’t always perfectly align like you might think they do. There are times when acting in the conservation interest of a species or ecosystem means that the welfare of specific animals is compromised, which is a fancy way of saying that conservationists sometimes have to kill animals for the greater good. Most fair minded people who are into animal welfare and animal rights accept this conservation need, even if they aren’t happy with it (and as I’ve said in the past, most conservationists aren’t thrilled by it either – there is after all a big overlap between those who want to save animals as those who want to save species). I’m not going to trash out the whole argument again, but my argument here is based on the acceptance of this uncomfortable premise. If you don’t accept that we sometimes have to do harm to individuals to do good for the species, well, nothing I’m going to say is going to convince you.

Cheetahs would be quite happy with you shooting Lions as Lions are bastards that keep stealing their kills. There is no solidarity among the big cats.

Cheetahs would be quite happy with you shooting Lions as Lions are bastards that keep stealing their kills. There is no solidarity among the big cats.

I guess the natural question is… how does some hunter from the US help in the conservation of the lion? The answer should be obvious to anyone familiar with wildfowl hunting in the US and the film Jerry McGuire – money. Hunters are prepared to spend a lot of money for the privilege of shooting a lion. Melissa Bachmann, the hunter at the centre of the current storm, paid around $125,000 to shoot her male lion, and that’s not a small amount of money for a single lion in rural Africa. Remember, that’s $125,000 for a lion in its natural habitat, not dismembered in a stall in a Chinese market. If you want to have the “thrill” of shooting a wild lion (not a canned hunt), well, you’re going to need a lot of land to sustain those lions.

Take the Selous Game Reserve in Tanzania. At 54,600 km2 (21,100 sq mi), its one of the largest faunal reserves in the world, and a World Heritage Site to boot. Let’s take a second and then about three paragraphs to look at what exactly is being preserved by this reserve, as listed in the World Heritage Site Index:

Criterion (ix): The Selous Game Reserve is one of the largest remaining wilderness areas in Africa, with relatively undisturbed ecological and biological processes, including a diverse range of wildlife with significant predator/prey relationships. The property contains a great diversity of vegetation types, including rocky acacia-clad hills, gallery and ground water forests, swamps and lowland rain forest. The dominant vegetation of the reserve is deciduous Miombo woodlands and the property constitutes a globally important example of this vegetation type. Because of this fire-climax vegetation, soils are subject to erosion when there are heavy rains. The result is a network of normally dry rivers of sand that become raging torrents during the rains; these sand rivers are one of the most unique features of the Selous landscape. Large parts of the wooded grasslands of the northern Selous are seasonally flooded by the rising water of the Rufiji River, creating a very dynamic ecosystem.

Criterion (x): The reserve has a higher density and diversity of species than any other Miombo woodland area: more than 2,100 plants have been recorded and more are thought to exist in the remote forests in the south. Similarly, the property protects an impressive large mammal fauna; it contains globally significant populations of African elephant (Loxodontha africana) (106,300), black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis) (2,135) and wild hunting dog (Lycaon pictus). It also includes one of the world’s largest known populations of hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibius) (18,200) and buffalo (Syncerus caffer) (204,015). There are also important populations of ungulates including sable antelope (Hippotragus niger) (7000), Lichtenstein’s hartebeest (Alcelaphus lichtensteinii) (52,150), greater kudu (Tragelaphus strepsiceros), eland (Taurotragus oryx) and Nyassa wildebeest (Connochaetes albojubatus) (80,815). In addition, there is also a large number of Nile crocodile (Crocodilus niloticus) and 350 species of birds, including the endemic Udzungwa forest partridge (Xenoperdix udzungwensis) and the rufous winged sunbird (Nectarinia rufipennis). Because of this high density and diversity of species, the Selous Game Reserve is a natural habitat of outstanding importance for in-situ conservation of biological diversity.With its vast size (5,120,000 ha), the Selous Game Reserve retains relatively undisturbed on-going ecological and biological processes which sustain a wide variety of species and habitats. The integrity of the property is further enhanced by the fact that the Reserve is embedded within a larger 90,000 km2 Selous Ecosystem, which includes national parks, forest reserves and community managed wildlife areas. In addition the Selous Game Reserve is functionally linked with the 42,000 km2 Niassa Game Reserve in Mozambique, and this is another important factor that ensures its integrity. With no permanent habitation inside its boundaries, human disturbance is low.

I think you could make a good case that this reserve is important. And here’s the kicker:

It is managed as a game reserve, with a small area (8%) in the north dedicated to photographic tourism while most of the property is managed as a hunting reserve.

The reserve is threatened, as many wild areas are, by poaching , encroachment and mining interests. It’s a vast place, and difficult to patrol. But this massive area of wilderness survives, and it survives to cater to the needs of rich people like Melissa. In fact, according to a paper in Biological Conservation:

A minimum of 1,394,000km2 is used for trophy hunting in sub-saharan Africa, which exceeds the area covered by national parks. Trophy hunting is therefore of major importance to conservation in Africa by creating economic incentives for conservation over vast areas, including areas which may be unsuitable for alternative wildlife based land uses such as photographic ecotourism.

I had a lecturer in my conservation masters who argued that all conservation (and environmental) problems were essentially economic ones, namely market failures. If there is no incentive to protect an area it will be very difficult to protect the area when there is money or a livelihood to be made destroy it. People generally don’t poach lions and rhinos because they hate them, they do so because they can make money doing so (or sometimes because said rhinos and lions threaten their existing livelihood). By placing a dollar value on the wildlife that requires that wildlife to be managed as opposed to wiped out, you create a situation where people have an economic interest in keeping both that wildlife and that habitat it needs. It’s an economic solution to an economic problem. Managing areas for hunting does exactly that. Shooting lions is big business. Lion shooting over three years brought $75 million into the economy of Tanzania alone. Lions are a resource, and one to be managed and protected.

In fact, managing an area so you can shoot some antelope an the occasional lion doesn’t just protect those species. It also protects hundreds of species of birds and mammals, and thousands of plants, and everything else you need in a functional ecosystem. Shoot a few lions in the Selous and you protect a viable population of African Wild Dogs, a much more endangered species. You protect an entire ecosystem that holds 350 bird species. You do a lot of good.

I’m not going to wave away the problems. A pitiful amount of the money it brings in to these countries actually reaches the people who live around these hunting areas, although in fairness this is hardly a unique problem in the tourism sector of Africa. There are of course disreputable operators who operate the infamous canned hunts, and there is always the danger that less reputable hunters will take more wildlife than can be sustained. But these are fixable problems. In the light of the good hunting does in Africa (remember those massive tracts of land being managed for wildlife?) these are arguments to fix hunting rather than ban it.

Oh, and then there are the hunters. And here’s the thing, we’ve already got them on our side, at least a lot of them. Not all of them, but a lot of them are conservationists. Enjoying hunting doesn’t preclude you from caring about conservation, just as being a conservationist doesn’t preclude you from enjoying hunting. I’ve certainly met my share of conservation professionals that hunt, and while I don’t hunt myself, I’ve done quite a bit of fishing while working on marine projects. Like with animal rights, the goals of conservation and hunting are not quite lined up, but they can be quite similar. Both are in favour of large areas of land being set aside for wildlife. Here in New Zealand in fact hunters have been an essential part of the protection of these island’s unique wildlife and ecosystems. Picking a fight with them when they already are on our side seems a good way to lose.

There is a self defeating tendency among causes people fight for to sacrifice achievable goals in the pursuit of ideological purity. The current Republican Party in the US is a classic “put it in the dictionary” example of this. If you care about conservation, if you wish to protect savannah and bushvelt and elephants and wild dogs and Kori Bustards and vultures and everything that makes the African wilds the astonishingly biodiverse and bewitching place it is, you cannot succumb to this tendency. Africa’s wild places have so many pressures as it is. Wildlife crime is exploding. Africa’s population is projected to double in the next forty years. Global warming is going to kick into high gear. Corruption means many reserves exist on paper only. Poverty leads many to poach and encroach to survive. To go after and hound hunting, which has a tiny effect on populations compared to habitat loss and poaching, and brings millions of dollars to bear on protecting species and habitat, and is supportive of conservation, to the point of actually funding it, isn’t just misguided, it’s utterly insane. We need to be pragmatic to win this fight, and this is the opposite of pragmatism.

So I’ll cheer Melissa Bachmann, and the other hunters that support us in the face of our intractable opposition. I’m glad they are on our side, because I’m fighting to win, and we’re going to need them.

Don’t let the sun go down on Africa’s wild places. Shoot something! (Again, views not necessarily shared by the management, void in national parks like this one)

I agree with you in that I view trophy hunting as a necessary evil given the realities in Africa and elsewhere.

I agree. Conserve populations, not individuals.

I too agree with Duncan’s excellent post.

In theory, this all sounds reasonable. But it falls apart when all relevant parties, such as governments and other officials, don’t buy in. I admit to being swayed by this talk at the Chicago Humanities Festival, from a researcher who’s spent his life studying lions and is now fighting to protect the few that are left:

http://chicagohumanities.org/events/2013/animal/the-other-safari

Lions are vulnerable but not endangered, they aren’t going anywhere. But wild lions are never going to be hunted much (excepting canned hunts, which aren’t wild). This article is about trophy hunting in general, we shouldn’t get too hung up about lions specifically.

Point well taken, Duncan. I understand that there are some instances where it’s, as Jochen says, hunting is the lesser of two evils.

I think this is a very well written piece, and I like how it points out that hunting and conservation are quite compatible is most cases. The only critical point I disagreement with is with what the lecturer in your conservation course said about everything boiling down to economics. I certainly think there are many economic benefits in the relationship between hunting and conservation as you so well point out. I guess it is just my personal dislike of the concept of (unsustainable) expanding economies and that nothing can be important if we don’t put an economic value on it. I think the economic benefits for conservation purposes that emerge from hunting activities are among a secondary set of outcomes that have been ingeniously captured by smart people. Also in this group of benefits are other civic outcomes (those that benefit society in general) like management of overabundant deer and snow goose populations that are having ecosystem-wide negative effects on hundreds of bird species and other wildlife. I think some of the most important beneficial outcomes are those accrued by individuals in terms of their connection to nature through hunting activities. This outcome rarely gets serious treatment in public discourse because its not easily understood or accepted by people who do not hunt. And let me be clear, I am not saying that the lady who shot the lion and posted about it necessarily experienced that feeling of being connected to nature via that particular experience. But I am guessing that in other instances, she probably has, and that is why she can claim to love both the animals she hunts and is willing to protect the habitat they depend on.

Thanks for the feedback Jody. This and other comments I have heard has prompted me to begin collecting material to discuss economics in conservation. I’ve heard your objections from other people, and I think the point deserves to be addressed at length.

Interesting. I’ve been around long enough to know that the answers to issues are rarely black or white, much more often shades of gray; I neither agree nor disagree with your viewpoint, though I take a dim view of the trophy aspect of hunting.

I question though your assertion in a response above that, “Lions are vulnerable but not endangered, they aren’t going anywhere.” I’m not sure what defines endangered or vulnerable, but I’d point you to this TED talk, in particular minute 12.45 and then later minute 14.30

http://www.ted.com/talks/beverly_dereck_joubert_life_lessons_from_big_cats.html

What I gathered from it is that the lion population has fallen from 450,000 to 20,000 in two human generations and that the loss of a pride’s dominant male has a significant mortality ripple effect on other lions within and outside the pride.