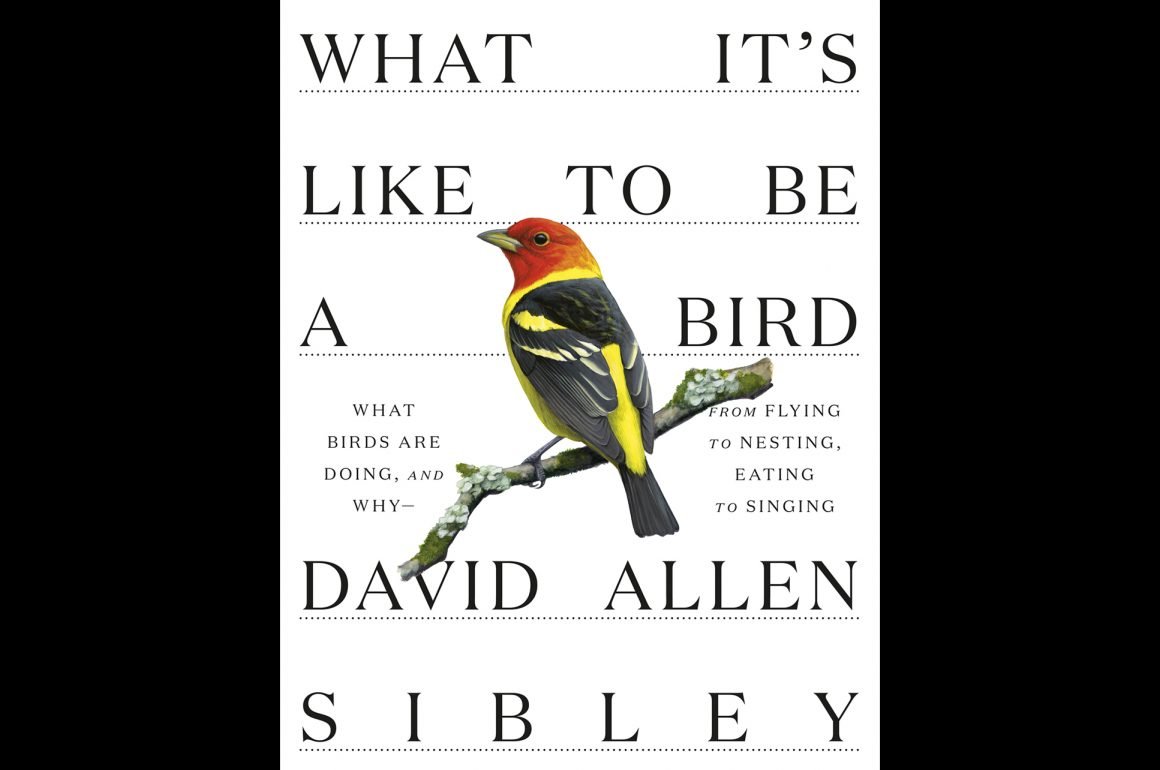

“Look around, look around…” The refrain is from Hamilton, a demand and a plea to look with the brain and the heart and then to look again. Listening to them, I thought the words could also be applied to one of the more positive phenomena of the past few months, though in a very different context. People stayed home and looked around. They looked out their windows and across their patios and up from their apartment terraces and saw–birds. And they were intrigued and they had questions, lots of questions, more questions than could be answered by a field guide or a social media group. Fortunately, with a prescience that’s a little scary, David Allen Sibley has created a book perfect for beginning birders (and the rest of us): What It’s Like to Be a Bird: From Flying to Nesting, Eating to Singing–What Birds Are Doing, and Why.

copyright @2020 by David Allen Sibley

This is a delightful book, large (8-1/2 by 11 inches), filled with Sibley’s distinctive artwork and an organized potpourri of research-based stories about the science behind bird’s lives. As Sibley tells us in the Preface, he originally intended to write a children’s book. Over the past 15 years the idea morphed into something different; he retained the large format and bird portraits, but focused on bird behavior, anatomy, and biology, the exceptional things about birds not covered in identification guides, the things that make us think and look and look around again with renewed appreciation and even awe.

The book is divided into nine sections: Preface, How To Use This Book, Introduction, Portfolio of Birds (the main section), Birds in this Book, What to Do If…, Becoming a Birder, Acknowledgments, and Sources. This is not a linear book; as Sibley explains, “… it is designed to be browsed casually, so that different topics will spark connections and perhaps even a sense of discovery” (p. viii). It is a book with a careful infrastructure, however (even though it doesn’t have an index), with references to one section from another, enabling the curious reader to go down structured rabbit holes, pursuing information on nesting or skeletal systems or feather structure throughout the book.

copyright @2020 by David Allen Sibley

The Preface gives a brief history of how the book came to be written (something I always want to know, so thank you, Mr. Sibley) and some of Sibley’s thoughts about birds. This was a pleasant surprise if only because I’m so used to the more technical views presented in his field guides. It’s nice to get a tiny glimpse of David Sibley the person. His view of birds as creatures constantly making decisions about their lives, in contrast to the idea that they automatically obey instinct like automations, is food for thought as one peruses the book.

How To Use This Book is brief, useful, and answers some questions I had, which we’ll get back to later. The longer Introduction lists and briefly summarizes topics covered in the Portfolio (evolution feathers, coloration, variation, senses, movement, physiology, migration, food and foraging, survival, social behavior, birds and humans, threats). The section is organized in PowerPoint-like outline format, organized by headings, subheadings, and sub-subheadings and with tiny bird-bullets setting off each information point. It’s an attractive design approach, an easy entryway for someone totally new to the subject. (Also, I wish I could use the tiny birds for my own presentations. Is a free digital download possible?) On a quick browse, here are some facts I learned: Melanin helps to resist bacteria that attack feathers; most parrots are left-footed and this is associated with problem-solving; some birds nest in two different places in the same year. Most importantly, this section provides an entry point to the major Portfolio of Birds section; each fact is followed by a page reference. So, curious about which birds nest in two places, I quickly found out that it’s Phainopepla, a western bird, a relief because I was concerned that it might have implications for my data collection for the NYS Breeding Bird Atlas.

copyright @2020 by David Allen Sibley

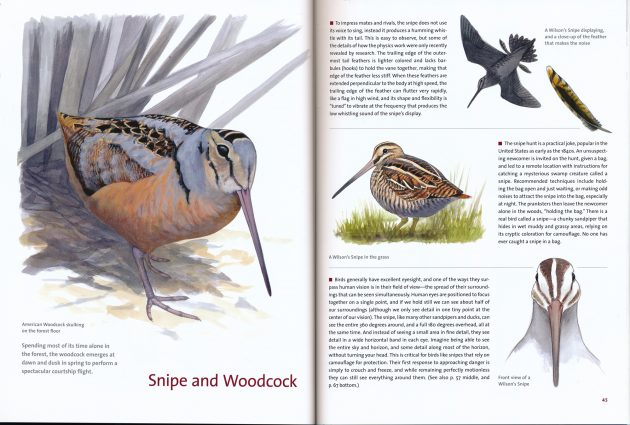

The Portfolio of Birds is comprised of 87 2-page spreads. Each spread consists of a full-page painting of a bird or group of birds on the left and a combination of text and illustrations on the right. The painting is annotated with chapter title, bird identification, and a bird fact, and it all fits together perfectly, the benefit of the artist and writer being the same person. The text is divided into three parts, informational stories or ‘essays’ as Sibley calls them. These are sometimes about the bird or birdgroup of the chapter title, sometimes (actually quite often) about all birds. In the Snipe and Woodcock chapter pictured below, for example, we learn about (1) recent research on how the snipe makes sounds with its tail (it’s all about shape and flexibility of the tail feathers); (2) the history of the ‘snipe hunt’ (a prank dating back to the 1840’s that is apparently part of American folklore); and (3) the Wilson Snipe’s amazing field of vision, enabling it to see 360 degrees around and 180 degrees overhead at the same time standing still, a trait also found in many species of sandpipers and ducks. If you want to learn more about avian visual field, the essay cites two related essays in the book on Eagles and Meadowlarks (though there is a typo–it should be p. 167, Meadowlark line of sight–not p.67).

copyright @2020 by David Allen Sibley

Three page spreads have a different format. They portray the nesting cycles of Mallard, Red-tailed Hawk, and American Robin, illustrating the various ways in which birds create families. I’m using the term ‘family’ instead of ‘procreate’ or ‘reproduce’ because I think these articles go to the heart of what many people, from toddlers like my granddaughter to older people like my apartment-dwelling neighbors, want to know about birds: How are they like us? How are they different? Do they have families too and do they take care of them? As in all the essays here, Sibley has a talent for encapsulating a lot of detailed information in very readable prose, and I’d love to see these nesting cycle essays retold in a different format, maybe that elusive children’s book. (I think every child should learn the word ‘precocial’ before the age of 12; precocial and ‘altricial’ are two of the few scientific terms used in the book.)

The essays are arranged in almost AOS taxonomic order, with changes made to lessen confusion for new birders–falcons are grouped with hawks, all water birds come before land birds, etc. Some of the chapters focus on a specific bird, most are about bird families like hawks, tanagers, wrens, etc., with additional sections added if there is just too much interesting information for a two-page spread (“Large Sandpipers,” “Small Sandpipers,” “More Owls,” and so on). The emphasis is on everyday birds seen in North America, though some of the more exotic and local species are thrown in for the color and romance of it all–Atlantic Puffin, Roseate Spoonbill, the poor extinct Heath Hen. There is also an effort to represent all geographic areas of North America, from Eastern Bluebird (below) to Greater Prairie-Chicken to California Scrub-Jay. This is seen nicely in the chickadee portrait, which shows a Black-capped Chickadee, Chestnut-backed Chickadee, and Mountain Chickadee on the same branch, “inspecting everything.”

copyright @2020 by David Allen Sibley

Sibley’s artwork is key to the joy of reading What It’s Like to Be a Bird. His field guides are known for images that simultaneously portray notable field marks and also the ‘personality’ of a bird species. Here, his full-page portraits, released of the necessity of drawing every single identification detail, burst with color and energy though never totally losing the clean-lined precision that is his trademark. In his interview with Nate Swick on the ABA Birding Podcast, Sibley explains how his use of acrylic paints, as opposed to the gouache techniques used for the field guides, allowed for painting with “big swaths of color and focus on the movement and action.” (I highly recommend listening to the podcast as a complement to reading this book.) The portraits are roughly life-sized, which is one of the reasons for the larger size of the book and range from extreme close-ups to birds or groups of birds in their habitat. My personal favorite is the night image of a White-crowned Sparrow beginning a night of migration, the sparrow’s usual bright white-and-black head and brown-patterned body muted by the inky blue darkness, the bill pointing upwards towards the stars. I would happily display this painting in my bedroom (so, please, Mr. Sibley, make a print).

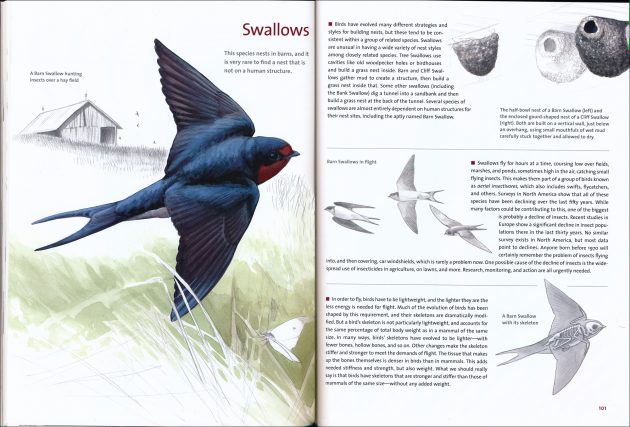

As a nice balance to the portraits, the essay pages feature smaller paintings, drawings, and diagrams illustrating the scientific stories. Look at the Swallow page shown in the beginning of this review: there is a comparison of Barn Swallow and Cliff Swallow nests; silhouettes of a Barn Swallow in flight; a skeleton of a Barn Swallow, bones stronger and stiffer than humans but not, surprisingly, heavier. Other illustrations include the evolution of a feather from a hollow tube to an asymmetrical flight feather on the Egrets page; anatomical drawings illustrate the physiology of the workings of a woodpecker’s tongue; a sonogram of a typical Chipping Sparrow song, a map showing the migration cycle of the Blackpoll Warbler (‘distance champion’ of the wood warblers), and much more. As I said before, the page design is impeccable. The artwork never overpowers the text and there is never any doubt which illustration belongs with which essay, the eye is always directed from one to the other. Despite the number of text and diverse images, each page is clean and balanced, a pleasure if you spend your days looking at crowded web sites.

I list these illustrations to give some idea of the variety of image and of topic, and also of the surprising depth of many of these brief essays. Though this is a book for beginning birders, Sibley doesn’t dumb down the answers, and there is a lot to be learned here by birders of all levels. Many of the essays are based on recent research, presented in the Sources section, and my only gripe is that there aren’t footnotes or citations within the text. I imagine the thought was that footnotes might scare off people new to the field or unfamiliar with academic writings. I disagree. A related issue is that some of the subjects Sibley writes about are complex and cannot be summarized, even by a talented writer, in one-third of a page. A good example is the function of beauty in male birds. Sibley writes, “Female choice may control the appearance of males.” But, if you’ve read Prum’s The Evolution of Beauty, the source that Sibley himself cites, you know this is a simplification of Prum’s theories and a controversial one. I was happy to see that Sibley acknowledges this drawback in the Introduction to his book, commenting, “Many of the topics involve recent discoveries and tantalizing possibilities, and are still being actively studied and debated by experts” (p.viii).

copyright @2020 by David Allen Sibley

Birds in This Book follows the Bird Portfolio. This section gives brief descriptions of the birds painted in the Portfolio section, sometimes elaborating on the behavior portrayed in the portrait (the advantages of flying at night for White-crowned Sparrow), sometimes giving additional facts of interest with a small dollop of humor (Greater Roadrunners are not in a perpetual war with coyotes). I’m not sure if this section is a necessity, but it is fun reading and it’s nice to read what Sibley chooses to say about these birds when he’s not writing up a field guide entry.

The What To Do If…. section answers many questions often posed by beginning birders and just plain people in social media groups and I’m sure elsewhere–What to do if a woodpecker is attaching your house, if you find a dead bird, if you find a baby bird, etc. Sibley’s answers are models of succinct common sense and I look forward to using some of his answers in the social media group I administer. Similarly, his section on Becoming a Birder gets to the core of the passion–be curious, be an “active observer,” limit the impact you have on the birds. And, though possession of a field guide is recommended, Sibley does not mention his own field guide, the inimitable The Sibley Guide to Birds, Second Edition. Instead, he advises on what traits and features to observe, with numerous references to essays on these features.

If you’re not familiar with the work of David Allen Sibley, here is a brief rundown: Sibley, self-taught artist and lifelong birder, wrote and illustrated the first edition of The Sibley Guide to Birds in 2000 and immediately elevated standards for field guides. His books since have included regional editions of his guide, The Sibley Guide to Bird Life and Behavior (2001), Sibley’s Birding Basics (2002), and the Sibley Guide to Trees (2009). His art is beloved (if you have owned a Sibley calendar at least once in your life, raise your hand) and his bird expertise is widely respected.

What It’s Like to Be a Bird: From Flying to Nesting, Eating to Singing–What Birds Are Doing, and Why is a natural addition to Sibley’s publication list. Unlike his earlier, more encyclopedic guide to bird life, this book capitalizes on Sibley’s artistic skills. It also utilizes an entertaining educational format, bursting with energy and fun. The book is a little pricey, the cost of a quality product with thick paper and outstanding inking. I think beginning birders would gain a lot from reading What It’s Like to Be a Bird. Sibley fans will enjoy exploring his bird portraits. This is also a great gift book that could be shared with the family (I showed my granddaughter the Robin nest drawings over FaceTime today and she was fascinated). More advanced birders will probably want to consider more traditional approaches, and there are a surprising number being published this year: Jennifer Ackerman’s The Bird Way: A New Look at How Birds Talk, Work, Play, Parent, and Think (Penguin Press, 2020), Marianne Taylor’s How Birds Work: An Illustrated Guide to the Wonders of Form and Function from Bones to Beak (The Experiment, 2020), and the forthcoming Peterson Reference Guide to Bird Behavior by John Kricher (HMH, Sept. 2020). More narrative, more dense, maybe a little less fun. But, whatever book you decide to read, first look around. And listen. And, then look again.

copyright @2020 by David Allen Sibley

All illustrations courtesy of David Sibley and Alfred A. Knopf; Copyright @2020 by David Allen Sibley

What It’s Like to Be a Bird: From Flying to Nesting, Eating to Singing–What Birds Are Doing, and Why

by David Allen Sibley

Sibley Guides Series; Knopf; April 2020

Hardcover; 8.8 x 1 x 11.3 inches; 240 pages

ISBN-10: 0307957896; ISBN-13: 978-0307957894

$35.00; Kindle $18.99

Leave a Comment