As my faithful readers know, I have a long-standing fascination with helping (and, at times, inadvertently confusing) interested non-birders – those who are entering the admittedly weird and wild world of birding for the first time. Lately this fascination has increased, not only because of my book project but because I’ve been invited by one group and another to speak to various audiences, from sixth-graders to adult learners, about getting started with birding.

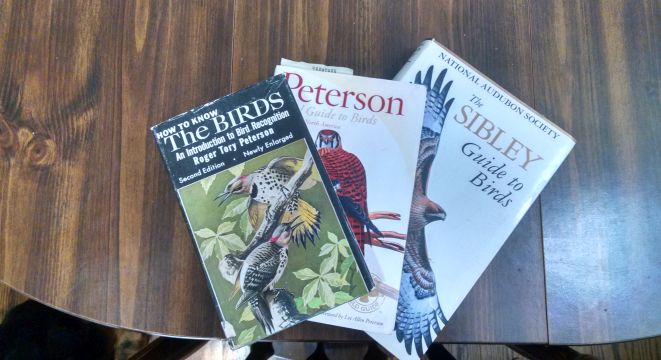

One of the first questions I’m always asked is about field guides. While the plethora of guides on the market is great for birders, it’s bewildering to beginners; I often find that newbies are paralyzed with the choice between Peterson, Sibley, Audubon, etc., etc… and once they have one, once again bewildered by where to even start looking for the bird in front of their face. As a wise man once noted, taxonomy does not make for intuitively laid-out field guides – why are the owls not up near the hawks, many a plaintive questioner has asked me – and many of the contextual clues that seem obvious to an old hand aren’t exactly clear to a novice. This was brought home to me in one class when a young girl got stuck on the idea that the female Mallard we were looking at might be a nighthawk, since it was a brownish bird in a horizontal pose.

With all of these things in mind, I’ve been more and more apt to recommend apps – Merlin and the like. I’ve seen Merlin guide beginners through exactly the sort of process – thinking of habitat, of GISS, of probabilities – that becomes second nature to experienced birders. It’s long been argued, after all, that the future of field guides is digital. But I’m not ready to write off paper guides even now – if only for reasons of accessibility and affordability.

What say you, blog readers? Have you found helpful techniques for explaining the stodgy old field guide and its weird hidden owls to the bird-curious in your life? Or are you encouraging everyone to get on board with the digital revolution?

I haven’t spent much time with beginners recently, but if I did, I would probably point them in the direction of a paper field guide (probably Sibley’s). I think one advantage of the paper field guides is that, by flipping through the pages, you can start to see the characteristics that separate one family from another. Being able to place the bird in a family is a big help when it comes to narrowing down an unfamiliar bird.

When I was starting out a few years back, I actually really liked a photo-based book that I found called “Birds of (State)” by Stan Tekiela (e.g. “Birds of Massachusetts”). I also had a Sibley and Peterson guide, but they were to detailed for where I was at.The Tekiela guide only had the most likely species (maybe around 120 of them), which really reduced confusion, and organizes by something like notable colors (I didn’t really use the color-based system much, though). I also found that the photos were much easier to identify based on, as I didn’t find illustrations easy to compare to what I was actually looking at. To my beginner self, it was almost impossible to tell which illustration the “little brown job” that I was looking at matched best, but somehow it was much easier with the photos.

“A wise man”? Manners, Carrie, manners. Didn’t your parents teach you to always be honest? But thanks …

Well, I can be a terribly conservative person at times and have so far never used digital ID tools. Heck, I don’t even own a smart phone! Therefore, I always point beginners to a good and comprehensive field guide. In North America, this would likely be a Sibley’s. Of course they will be overwhelmed at first by the variety, but the most important lesson I give them in addition to my field guide recommendation is always to make extensive use of distribution maps and read the texts. Beginners tend to only look at the pictures of a field guide and not on the maps and the text.

I do not like field guides that do not show all the species for a certain region but only those “most likely to be seen”, “feeder birds” etc., because very few things can be more frustrating to a beginner than finding out a certain species they saw and struggled to ID was simply not included in their field guide. Especially as a beginner, a field guide is an instrument you’ve got to have trust in, and to be shown that it is unreliable since it omits many species can be really frustrating.

So, I’d recommend a field guide and give hints on how to use it.

I agree with Jochen, nothing is more frustrating for a beginner (and with not yet 3 years of birding I still am) than a field guide that only has the most likely birds, I’ve wasted countless hours doubting what I actually saw. Regarding the distribution maps – I would have made one or two very embarassing misidentifications if not for them… 😉 I find myself checking the maps first if I think I’ve seen a rarity. None seen so far.

My husband has been trying to convince me to go digital, but I find I prefer paper books, especially ones with illustrations. Unlike Aaron I find it hard to match photos to birds I saw, because sometimes colours are a bit off (depending on light / weather / surroundings) and I get… not confused, but again start self-doubting. With illustrations I know it’s not real life and adapt my perception more easily, if that makes any sense.

And another advantage of books is getting familiar with birds you haven’t seen yet – my very first kingfisher was identified by book knowledge and a silhouette: https://maycontainnuts.wordpress.com/2013/08/03/the-pure-joy-of-birding/

Predictably, I suppose, I always steer new and potential birders away from e-guides — I’ll change my mind in an instant once a digital book has been produced that is as fast and easy to use as a printed codex. Could be a while.

But most of all, I tell beginners that no book is going to help them as much as a notebook and a more experienced friend. Hobbies are perhaps the one area in our modern lives with a still vibrant oral tradition, and I hate to see anything come in the way of live and personal transmission of knowledge.

Yes, yes, yes: READ the field guide! Amazing that it has to be said, but it’s a very important piece of advice.