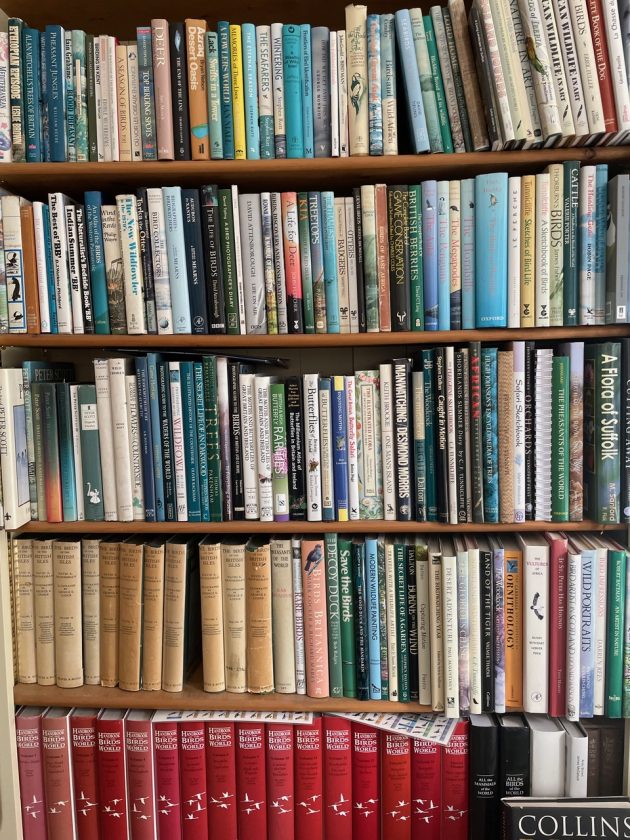

I’m sitting writing this in my study, its walls lined with books on birds and natural history. However, a worrying thought has struck me: is the book as we know it doomed, destined to die out as surely as the Dodo and the Passenger Pigeon? In my pocket is my iPhone (a modest 12 Mini), and among the apps I have loaded on it is the latest edition of the Collins Bird Guide along with Birds of the Western Palearctic (BWP). I used to have all nine volumes of BWP on my shelves, where they took top an awful lot of shelf space. I gave them away because I no longer needed them – all the text, all the illustrations and maps, are on both my phone and on my iPad. What’s more, it’s much easier to check facts digitally, rather than getting the book off the shelf and looking up the index.

However, having said that, I still love books. I do have the latest 3rd edition of The Collins Bird Guide as a hardback (as well as the previous two editions), and I get much more satisfaction looking through it than I do using the digital version. That might be because I’m old and set in my ways. I’ve always had an enthusiasm for books, and over the years I’ve reviewed many, written a few, and bought a lot. A good book is something to savour, but I admit that if you’re a travelling birder its great to have all the information instantly available on your phone, and not have to pack a book in your luggage.

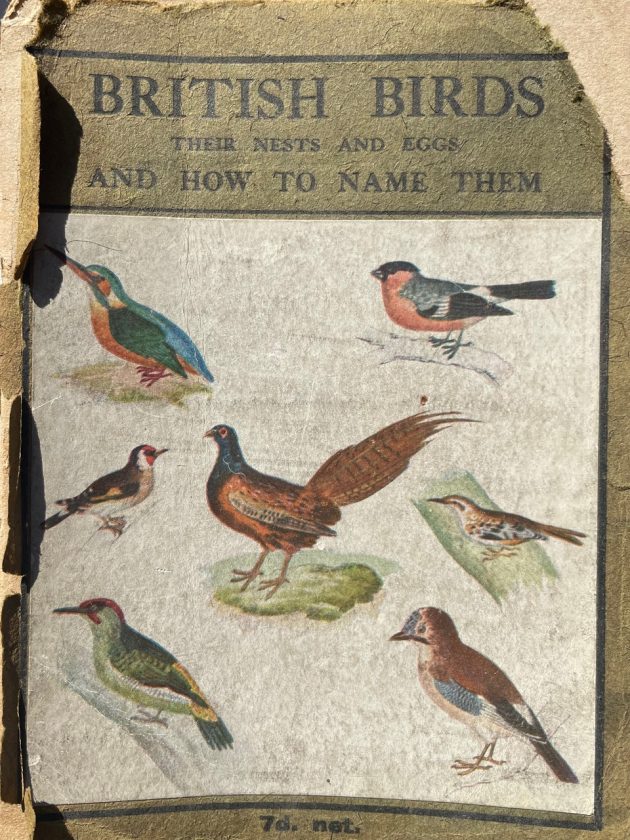

Bird books as we know them today originated in the last century. Of course, in the 19th century there were wonderful limited-edition bird books produced by people like John J.Audubon and John Gould, but they were hugely expensive and way out of the reach of ordinary people. One of the oldest bird books I have is titled British Birds Their Nests and Eggs and How to Name Them. Written by Walter M. Gallichan and illustrated with 81 drawings by F.H.Gallichan (his wife?), it was published by Holden & Hardingham in London in 1914. It cost 7d (seven pence, or about £4 in today’s money) for the paperback edition.

It has a simple charm that you can’t help but smile at. In his preface, the author notes that “The pleasure of a country walk at all seasons of the year are increased by the faculty of recognising birds of various kinds at rest or on the wing. Birdwatching is now a favourite recreation, and the science of ornithology has many distinguished and enthusiastic students. This little book is written for lovers of Nature who are not well acquainted with the birds of the hedgerows, moorlands, woods and the seashore, and who wish to learn how to identify the different species which they may see during a ramble in the country.”

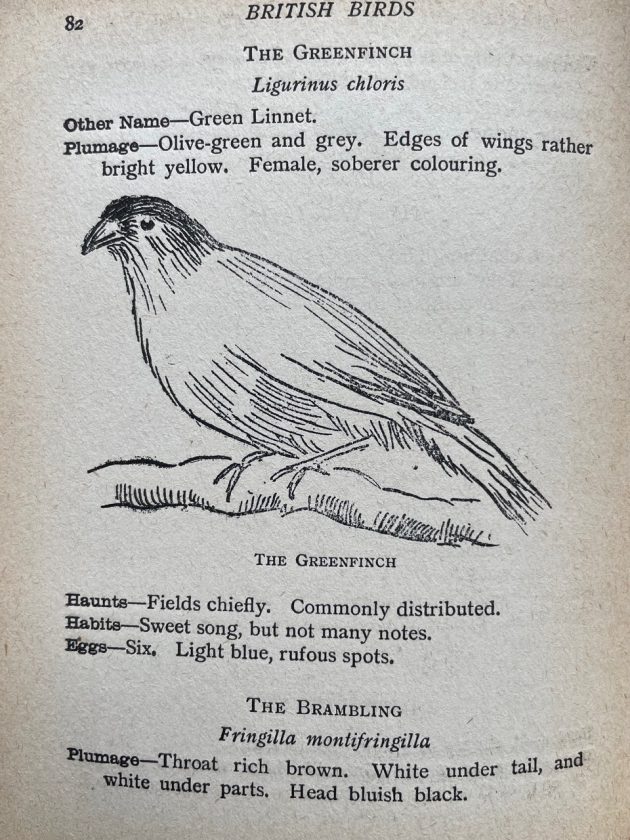

The quality of bird illustration has improved considerably in the last 100 years.

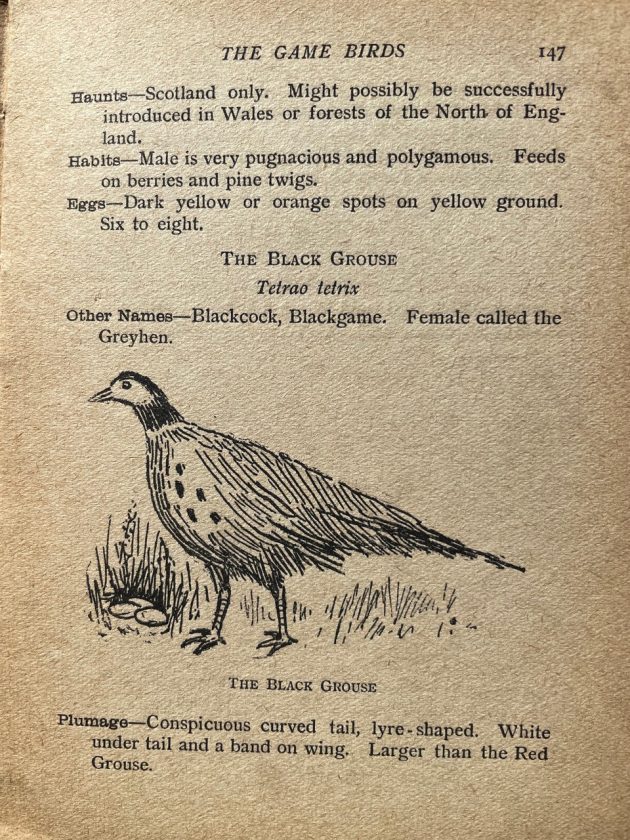

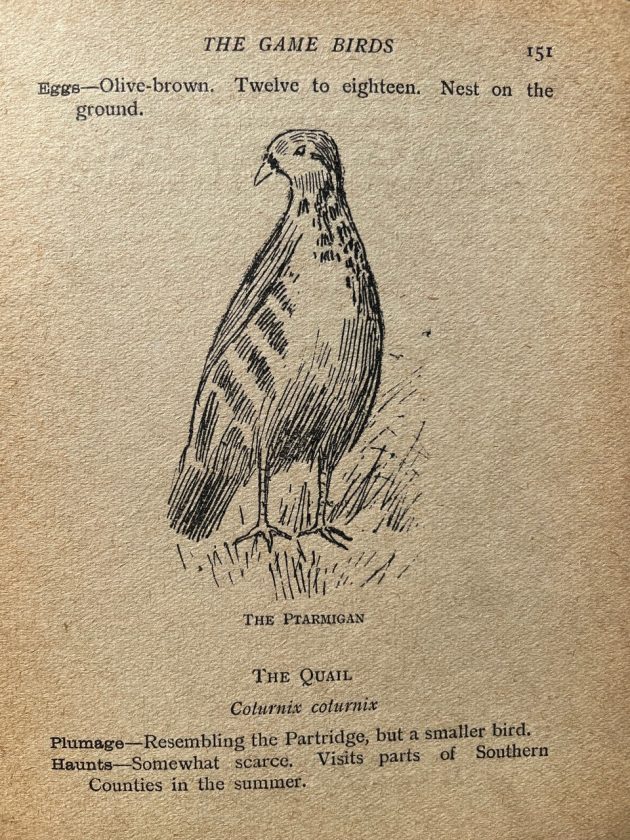

That sounds encouraging, but I’m not sure that many beginners would have really identified anything with the help of this book. The drawings, apparently drawn from specimens in the Rochester Museum, leave, shall we say, something to be desired. My favourite is the Greenfinch, shown above, but there are few, if any, which would be of very much use as identification aids. The texts have an appealing simplicity. Birds are lumped together chiefly because of their plumage, so Group I is Birds of Black or Dark Plumage, while Group III is Small Birds of Sober Plumage. Sea and Shore Birds form Group VI, while The Game Birds make up Group VII. Though it’s hard to be sure, I think that the bird labelled The Black Grouse is on fact a cock Pheasant, while the Ptarmigan looks like… well, I’m not sure really.

Isn’t that meant to be a cock Pheasant?

A very curious-looking Ptarmigan

Some texts are more helpful than others. Can you recognise this one (clue – it’s a shore bird):

Plumage – Black back, shading to light brown and grey. Head and neck striped black.

Haunts – Seashore and marshes. Usually in companies.

Habits – Winters in England.

That’s all there is to go on, and there’s not even a picture. (Answer at the end of this article).

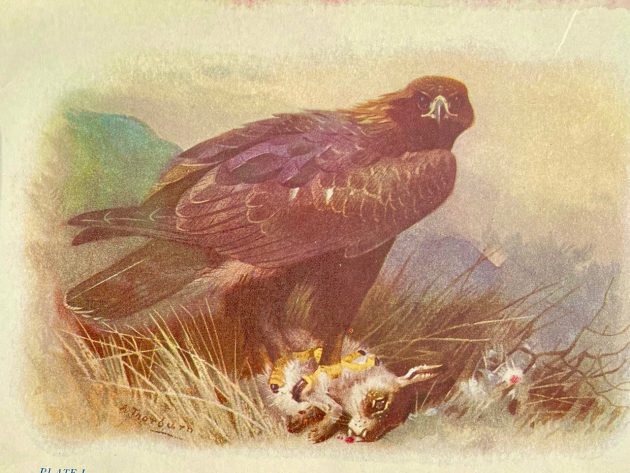

There were, of course, superior bird books available. W.H.Hudson’s British Birds was first published in 1895, and is a splendid work, though not the sort of book you would take in the field. Each species has its own highly readable essay, with numerous black and white illustrations by George Lodge, and eight colour plates by Archibald Thorburn, both leading bird artists of their day. My edition, a New Impression, was published in 1918.

A Golden Eagle, painted by Archibald Thorburn for Hudson’s British Birds

Hudson’s writing is typical of its time, but despite being old fashioned and at times pedantic, it’s highly readable. For example, we are told that the Sedge Warbler “sings a great deal at night in the love season” (true), while the charm of the Blackbird’s song “consists in the peculiar soft, rich, melodious quality of the sound, and the placid, leisurely manner in which it is delivered”. He regarded the Song Thrush as being “in the very first rank of British medalists, and it often said of him that he comes next to the nightingale”. Hudson frequently used the prefix ‘he’ when writing about birds.

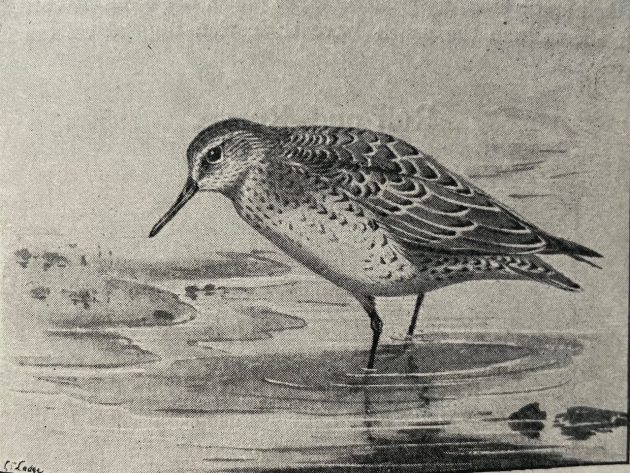

British Birds featured eight colour plates by Thorburn, including this Dotterel. His work is much sought-after by collectors today

Can you guess which bird Hudson is writing about here? “This richly coloured and pretty sandpiper with a strange name is one of two species in this order of birds of which the eggs are not known to ornithologists or do not exist in collections. It is a regular visitor to the British coasts on migration in August, but many birds remain until the following May. In some seasons they are very abundant, especially on the northeast coast of England; and in former times they were esteemed a great delicacy, and were netted in large numbers to be fattened, like dotterels and ruffs and reeves, on bread and milk for the table.” Hudson didn’t have the Internet to to rely on to check his facts: the eggs of this sandpiper had been first found by zoologist and Arctic explorer A.Birula on the New Siberian Islands (in the extreme north of Russia) in 1886.

To be continued.

The answer to both questions is the (Red) Knot, Calidris canutus. The illustration (above) of a Knot was drawn by George Lodge for Hudson’s British Birds

An interesting question … I am wondering about this as well. I have slightly more than 1000 bird books here but it has been a while since I last took out one of the volumes of the Handbook of the Birds of the Word – reading it online is just much more convenient … Though it is a bit sad, but as a person who has about 30,000 CDs spread in locations in Germany and China – and who has not listened to a single one of them in their physical form in the last year or so – I think Dodo it is for bird books … (though given the quantities of bird books people like you and me have piled up, the Passenger Pidgeon might be a more appropriate metaphor).

On-line is nice, a book is better. The physicality of the book appeals to me. I really like books. It’s when authors decide to no longer “do” books the bibliophiles are in trouble. The Dodo went extinct because of human action, the book might go the same way for the same reason and humans will regret it 300 years from now (I hope there will be regret because nobody mourns the fax machine).

At my bird club, we have a book sale in December every year. Members bring in bird books they don’t want. Other members buy them. People go home with armfulls. Bird books are beloved by birders, so they’ll never disappear. I have some old books with charming descriptions of birds and their behaviors, too. David, I would enjoy browsing your bookshelves.

Wonderful post, David. I miss the delicate illustrations in old books but agree that they don’t do much to help with identification they way modern apps do. But I hope Leslie is right and that theses books will never disappear.

Actually, that is the question for the gen Z. I will always cherish books, and talking of the Collins guide, I have the app on my phone, edition #1 as a paperback, and then both #2 and #3 as both paper and hardbacks. You make it, I will buy it!