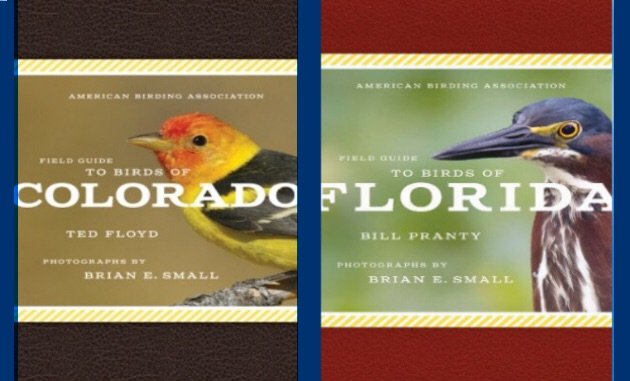

I was birding one of my favorite places yesterday, Wakodahatchee Wetlands in Palm Beach County, Florida, and, as generally happens, people were asking me about the birds they were admiring. This is what happens when you wear binoculars and a hat that says “NJ Audubon”. I was happy to answer the questions. “Great Egret.” “Roseate Spoonbill. Yes, it’s pink too.” “Blue-winged Teal. Yes, the female does look different.” But, I was wishing that I could also hand over to each curious person a copy of the American Birding Association Field Guide to Birds of Florida by Bill Pranty. This latest addition to the ABA State Field Guide series is sorely needed in places like Wakodahatchee. Like the two previous books in the series, the American Birding Association Field Guide to Birds of New Jersey by Rick Wright and the American Birding Association Field Guide to Birds of Colorado by Ted Floyd (photographs for all three primarily by master photographer Brian E. Small), it provides a friendly and authoritative way for people interested in the birds around them to learn more quickly and easily. I reviewed the New Jersey volume in May 2014 and, being in Florida at the moment, I thought this was a good time to take a closer look at both the Florida volume, published just last month, and the Colorado volume, published in June 2014. (I will be referring to the guides by simply their state names for the rest of this review, I think that makes it easier for both writer and reader.)

I was birding one of my favorite places yesterday, Wakodahatchee Wetlands in Palm Beach County, Florida, and, as generally happens, people were asking me about the birds they were admiring. This is what happens when you wear binoculars and a hat that says “NJ Audubon”. I was happy to answer the questions. “Great Egret.” “Roseate Spoonbill. Yes, it’s pink too.” “Blue-winged Teal. Yes, the female does look different.” But, I was wishing that I could also hand over to each curious person a copy of the American Birding Association Field Guide to Birds of Florida by Bill Pranty. This latest addition to the ABA State Field Guide series is sorely needed in places like Wakodahatchee. Like the two previous books in the series, the American Birding Association Field Guide to Birds of New Jersey by Rick Wright and the American Birding Association Field Guide to Birds of Colorado by Ted Floyd (photographs for all three primarily by master photographer Brian E. Small), it provides a friendly and authoritative way for people interested in the birds around them to learn more quickly and easily. I reviewed the New Jersey volume in May 2014 and, being in Florida at the moment, I thought this was a good time to take a closer look at both the Florida volume, published just last month, and the Colorado volume, published in June 2014. (I will be referring to the guides by simply their state names for the rest of this review, I think that makes it easier for both writer and reader.)

Though all the books in the series share common elements of design, structure, and photography, each one is written by a different author–a noted birder/writer who lives in and actively birds the state he is writing about. Choices have been made as to which birds to cover (none of these introductory guides are comprehensive, which is, I think, a good thing), and how to describe each bird’s appearance, distribution, and habitat in limited space. So, each guide has an individual personality. Colorado is written by Ted Floyd, editor of the ABA’s Birding magazine, author of the Smithsonian Field Guide to the Birds of North America and over a hundred popular and scientific articles, and active Colorado birder (he is currently on the board of directors of Colorado Field Ornithologists and, I’m sure, a part of many other state and local activities). Florida is by Bill Pranty, central Florida resident, author of A Birder’s Guide to Florida, now in its fifth edition, plus numerous articles documenting the distribution of birds in Florida, current chair of the ABA Checklist committee, and an active member of the Florida Ornithological Society.

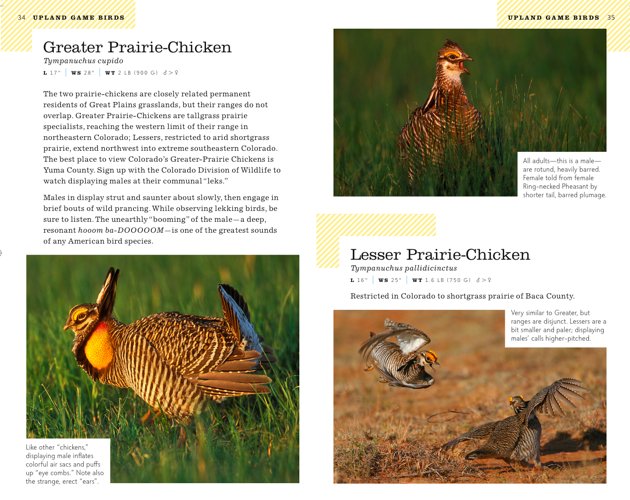

From the ABA Field Guide to Birds of Colorado

From the ABA Field Guide to Birds of Colorado

Here are the basic contents for each state guide: a flexibound cover, the ABA Mission Statement and Code of Ethics (I like that this is the first thing you see when you start perusing the books), Foreward by Jeffrey A. Gordon, president of the ABA, an Introduction, Species Accounts, Acknowledgements, Image Credits, a Checklist of the Birds of the state, and a Species Index. In addition, there is a Quick Index on the inside back cover and a map of the state displaying counties and birding hotspots on the inside front cover.

The flexibound cover is plain but sturdy, and I’m happy to see that there is a different color for each title. The binding also appears to be strong; I’m able to open to Prairie Falcon in Colorado, pressing open the pages so they lie flat, without fear that I will crack the spine. (It’s not that I like maltreating book spines, but I do like to see if field guides can actually be used in the field, where we sometimes have to fight wind and other factors to get a clear view of the book.) At 4.5 x 7.25 inches, the books can be easily carried in a large pocket or small backpack.

Species Accounts in both titles are arranged loosely in ABA Checklist order, with some flipping around of order within each family. This is clearly done to allow readers to view similar species opposite each other. It works well in Florida, in which most species are allocated one page each and 20 species get two-page spreads. But, the ordering gets tricky in Colorado, in which space allocation per species is highly variable. (It ranges from three pages for Dark-eyed Junco (all six subspecies) to two-page and one-and-a half page accounts for common species to one-page and half-page accounts for common and uncommon species to a photograph and one line of text for selected local, uncommon, and rare species.) As a consequence, two of the Empidonax Flycatchers, Willow and Least, are separated from the other four covered by the guide (Dusky, Hammond’s, Cordilleran, Gray), making it difficult to do comparisons of these very similar looking species. It must have been a struggle to fit over 300 Colorado species (I counted 302, but I may have missed a couple) into 264 pages. The Florida book’s organization and “look” benefits from an expansion to 322 pages for species accounts, covering about the same number of birds.

Each book covers roughly 60 percent of the state checklist, focusing on birds most apt to be seen. This may not sound like a lot, but when you consider the number of vagrant and accidental species that have been added to each state’s checklist over the years, you realize that there will probably be few birds seen by the beginning birder that aren’t here. (Unless the birder goes on a pelagic; Pranty does not cover any of Florida’s 17 pelagic species, as he himself notes.) And, it is 30 % more than the number of species covered by its nearest competitor, the National Geographic state series (which appears to be going out of print). Any more species, and I think beginners would be overwhemed and confused.

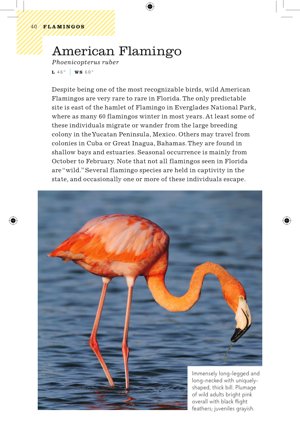

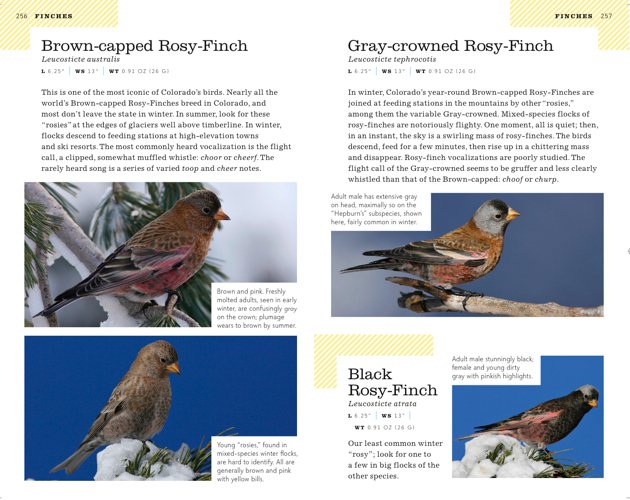

Pranty had a particular challenge for Florida, where exotics and feral forms of species like Mallard are seen throughout the state, especially in the southern peninsula. He solves it by including the most common exotic and feral birds in the species accounts alongside other birds, not differentiating “countable” birds (on the ABA checklist) from the “uncountable.” In addition, he adds ten exotic/feral species to the checklist in the back of the book, astericking them as non-official checklist birds. At first, I was taken aback by this approach. But I quickly realized that the countability of Red-masked Parakeet means very little to nature enthusiasts and beginning birders; they simply want to know more about the birds they see flying in to roost every night. This practice also prevents the guide from quickly becoming outdated. Egyptian Goose, for example, astericked as an exotic, was accepted onto the checklist in the brief period between when the book was written and when it was published. My only question is, why not more? I know, there are so many exotics in Florida, and so many of them are only seen in small areas. But, I was surprised not to see Mitred Parakeet, a bird I’ve seen regularly on every visit to southeast Florida, in the guide nor on the expanded checklist. (Disclosure time: I bird Florida, mostly the southeast area, several times a year. Thank you, little sister. I have also birded Colorado, but sadly, only two times. During the last visit in 2011, I was fortunate to see all three Rosy-Finch species at Red Rocks Park. But, that’s for a different post.)

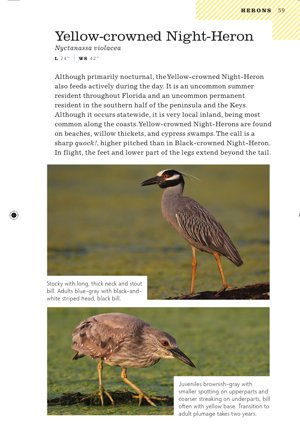

From the ABA Field Guide to Birds of Colorado

Species Accounts for entries in both guides start with the bird’s common name, followed by scientific name, measurements (length and wing span; weight in Colorad0 and also, in Colorado, symbols indicating if one gender is larger than the other). Text summarizes the status of the species in the state (permanent, summer or winter resident, migrant); its seasonal and geographic abundance; habitat; and transliterations of call and/or song. There is a lot of attention given to where and when the bird can be found within the state, specific locations sometimes given, supplementing the birding hotspot information offered in the Introduction.

As I said above, each title reflects the expertise and personality of its writer. Ted Floyd’s descriptions in Colorado exhibit a free-flowing enthusiasm for Colorado birding and its birds. On Bullock’s Oriole: “This radiant songbird is gratifyingly common statewide.” On Broad-tailed Hummingbird: “Once you get to know the shrill trilling of the male’s wings, you realize that the Broad-tailed Hummingbird is fantastically abundant in Colorado’s mountain forests.” On Black Rail: “The west end of the [John Martin Reservoir] is especially good; go there at dusk on spring evenings, and you are nearly guaranteed to hear one or more black Rails. A generational ago, nobody knew any of that!” His tone is relaxed and conversational, noting species that have expanded or restricted their range, locations of breeding populations, what call or song is best to listen for, and generally communicating what a joy it is to bird this state of mountains and plains and rivers.

Pranty’s text and bird descriptions exhibit his encyclopedic knowledge of bird distribution, current and historical, throughout Florida–panhandle, peninsula, Keys, and Dry Tortugas. The account for Sandhill Crane, for example, notes the resident “Florida Sandhill Crane” population in the peninsula and the separate, migratory “Greater Sandhill Cranes.” The Snail Kite population “has waxed and wanted according to local water levels and water-management issues”; he also notes that “the recent, rapid colonization of Florida by a South American snail–apparently the result of ‘aquarium dumping’ by hobbyists–seems to be aiding the Snail Kite population by providing an additional and abundant food source.” Pranty’s tone is more business-like and understated than Floyd’s, his text follows a set pattern whereas Floyd’s tends to deviate according to what he thinks is the most important thing we should know about the bird. Yet, there are times when Pranty’s enthusiasm for a specific bird shows through–Chimney Swifts are “amazing birds,” the adult Golden-winged Warbler is “stunning,” the Florida Scrub-Jay “is found nowhere else in the world.” Both authors communicate an amazing amount of information, more than simple identification, in a paragraph.

From the ABA Field Guide to Birds of Florida

Species are illustrated by one to three photographs, showing the bird perched and in flight or different forms of the birds according to gender or age. The photos are annotated with physical descriptions of the bird, differentiating between male and female, adult and immature, fall and spring, offering tips for identification in the field. These are state guides, not comprehensive guides, so in some cases, only the form of the bird most commonly seen in the state is depicted. Florida, for example, has only one photo of Yellow-rumped Warbler, in winter plumage, because that is how the bird is commonly seen there. Colorado, on the other hand, has the challenging job of depicting both populations of this warbler, Audubon’s and Myrtle, and explaining the difference between the two in two pages and three photographs. (A challenge with Floyd meets admirably, adding a note about hybrids.)

The photos themselves are mostly by Brian E. Small, who was photographic editor of Birding magazine for over 15 years, primary contributing photographer to the Smithsonian Field Guide to the Birds of North America, co-author of Birds of Western North America: A Photographic Guide and Birds of Eastern North America: A Photographic Guide from Princeton University Press, and contributor to many other magazines and books. Additional photographs are by a small group of photographers including Mike Danzenbaker and Alan Murphy. Interestingly, there is little overlap. I did find some photographs used in both guides, notably the impressive male Bald Eagle and the 2015 ABA Bird of the Year, Green Heron. I think this is something that will be hard to avoid as the series rolls out. Since most beginning birders will be likely to own one or two guides, I don’t see it as a problem; in fact, I think it’s remarkable that there isn’t more duplication. The photographs are clear, sharp, and show well the shapes, colors, and field marks described in the annotations. At the moment, I have Colorado open to Lazuli and Indigo Buntings and Florida open to Vermillion Flycatcher. The blues and reds are glowing in the light of my desk lamp, making me ache to see these birds again, in real life.

The Introduction to each guide includes tutorial information for the beginning birder (How to Identify Birds, How to Use Species Accounts, The Parts of a Bird, a section on Bird Song or, as Floyd titles it, “Listen Up”) and specific information on birding in the state. For Colorado, this takes the form of “a one-year birding tour”, listing month-by-month, the best place to be to see the best birds of that time of the year–the San Luis Valley in mid-March for Sandhill Cranes, the Prewitt Reservoir in August for Baird’s Sandpipers, October in Rocky Mountain National Park for White-tailed Ptarmigan (that’s where I’ll be). Pranty takes a different approach, listing first Florida’s diverse habitats and the species likely to be found in each one, and then listing the state’s top 30 birding sites by geographic area, followed by a Birding Calendar, describing migration and breeding patterns month-by-month. Both Introductions offer a section on Resources for further learning and keeping up-to-date. Colorado includes books, websites, listservs, and organizations. Florida includes books, websites, and listservs, but surprisingly omits mention of the over 40 Audubon Society chapters in the state, other than Tropical Audubon’s online BirdBoard. I would love to see a reference to a couple of the most active groups, or to the Audubon Florida web page, in a future edition.

The American Birding Association Field Guide to Birds of Colorado and the American Birding Association Field Guide to Birds of Florida are terrific additions to the ABA State Field Guide series and to the body of U.S. field guides in general. It is so important that we have these books. They are needed. As anyone who participates in birding social media knows, online groups for birders are multiplying and expanding, populated by people whose curiosity is piqued by birds, and who want to know their names and more. The ABA State Field Guides are the bridge between knowing nothing (or worse, knowing the wrong things, think about flamingos and spoonbills) and acquiring a strong, accurate foundation of the basics of bird identification. As I said in my New Jersey review, this is one of the most important initiatives the ABA has started in recent years. These are the perfect guides for the beginning birder, the high school student, the nature enthusiast, and maybe even those family members who live in Florida (or Colorado) and who you’ve been trying to convert to birding for years. I would consider purchasing the guide for your state even if you are an intermediate or advanced birder; there are nuggets of local expertise here that you won’t find in Sibley’s or National Geographic. I can’t wait for the 2015 state field guides to arrive, especially the ABA Field Guide to Birds of New York by Corey Finger. The one with the Cedar Waxwing on the cover. That’s going to be a fun book to review!

—————————

A big thank you to George Scott III and Scott & Nix for the review copies and the photo files.

American Birding Association Field Guide to Birds of Colorado (American Birding Association State Field Guide series), by Ted Floyd, photographer Brian E. Small.

Scott & Nix, Inc., June 2014.

320 pages; 0.8 x 4.8 x 7.5 inches, $24.95 (see usual suspects for discounts)

ISBN-10: 1935622439; ISBN-13: 978-1935622437

American Birding Association Field Guide to Birds of Florida (American Birding Association State Field Guide series), by Bill Pranty, photographer Brian E. Small.

Scott & Nix, Inc.,December 2014.

368 pages; 1 x 5 x 8 inches, $24.95 (see usual suspects for discounts)

ISBN-10: 193562248X; ISBN-13: 978-1935622482

Leave a Comment