One of the joys of blogging for a widely read blog is that it gives one a platform on which to moan and complain about subjects which interest the blogger and no one else in particular. In that particular spirit I hope to set the record straight on two separate issues that revolve around a genus of parakeets found mostly, but not exclusively, in New Zealand. The genus is Cyanoramphus, and they are sometimes known collectively as the kakariki (literally little kaka).

Yellow-crowned Parakeet, Cyanoramphus auriceps. Timmy Williams, (Creative Commons Attribution Share-alike Non Commercial)

What set this off? Picking up a bargain copy of the latest edition of the Parrots of the World by Joseph Forshaw. It’s a great book, don’t get me wrong. The illustrations are lovely and the cverage everything you’d expect from world experts. Joseph has forgotten more than I will ever know when it comes to parrots. But I’ve spent a lot of time working with kakariki, museum specimens, and the treatment of the genus in the book doesn’t match up with what I know.

Let’s back up a little bit and introduce the parakeets. The kakariki are an odd group of parakeets, particularly in terms of their distribution. They occur, or have occurred, on almost every island in the far-flung archipelago that is New Zealand, from the subtropical Kermadecs in the far north to the sub-Antarctic and treeless Antipodes (the only group from which they never seem to have occurred is the tiny Snares group). In addition they are (or were) found on the Australian islands of Lord Howe, Norfolk and Macquarie, as well as the larger tropical New Caledonia. In addition to this tight clustering of related parakeets, the genus also had two species in the far-flung Society Islands (now in French Polynesia). These species, recorded by early European explorers, are now sadly extinct, but the disjunct distribution is something of a mystery. It was long expected that the fossil record would show extinct members of the genus in the islands between New Zealand/New Caledonia and the Society Islands (places like Tonga, Fiji, the Cook Islands) that had gone extinct before Europeans arrived, but no such fossils have been found.

My first complaint about Forshaw’s treatment of the kakariki is taxonomic. He lists four extant species, along with the two extinct species. These are the insular endemic Antipodes Parakeet (Cyanoramphus unicolor), the largest species and one famous for digging up storm-petrels to eat (I guess there aren’t many fruiting trees on the windswept Antipodes); the Orange-fronted Parakeet (Cyanoramphus malherbi), a critically endangered species now restricted to a few spots on South Island; the Yellow-crowned Parakeet (Cyanoramphus auriceps) a widespread species found on the main islands of New Zealand as well as the Chatham and Auckland Islands, and finally the Red-crowned Parakeet, (Cyanoramphus novaezelandiae) found from New Caledonia to the Auckland and Antipodes. Lumped with the Yellow-crowned Parakeet is the rare Chatham form forbesi, and the Red-crowned Parakeet has numerous subspecies, hochstetteri (Antipodes), cyanurus (Kermadecs), cooki (Norfolk), saissetti (New Caledonia) and chathamensis (the Chathams).

Orange-fronted Parakeet (Cyanoramphus malherbi) Jon Sullivan, (Creative Commons Attribution)

Orange-fronted Parakeet (Cyanoramphus malherbi) Jon Sullivan, (Creative Commons Attribution)

Perhaps I should be grateful for four species. Heather and Robinson, in the definitive field guide for New Zealand, list only three, lumping the Orange-fronted Parakeet as a morph (not even a subspecies!) of the Yellow-crowned Parakeet. Such a classification is perhaps justified if you are only looking at external morphology and plumage. The Orange-fronted Parakeet varies very little from that of the Yellow-crowned Parakeet. Compared to that of say the Collared Kingfisher, for example, it would hardly raise an eyebrow.

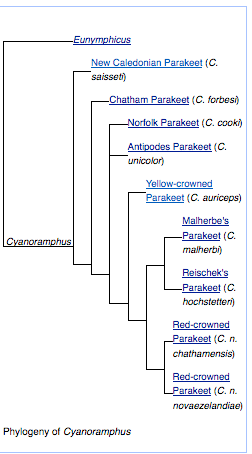

Implicit in such a view is that New Zealand was the evolutionary home of the genus, and that it has radiated out from there across the Pacific. This view, along with the taxonomy, is actually wrong, and has been out of date for almost a decade. Wee Boon, a student at Victoria University of Wellington (the place I attend), examined the DNA of as many species and subspecies of kakariki as he could in order to construct a phylogeny of the genus. The results were surprising, not just in how it elevated a number of subspecies to species level, but for the evolutionary history that the phylogeny revealed.The kakariki are not a New Zealand genus, they seem to have originated in New Caledonia. That is where their closest relatives, the horned parakeets of the genus Eunymphicus, are found. It also showed that the New Caledonian Red-crowned Parakeet was a separate and basal clade within the genus. The ancestor of both genera appears to have come from Australia, possibly from stock that also have rise to the rosellas, at least 20 million years ago. Incidentally the two genera form a sister clade to another Pacific genus, Prospeia, the shining-parrots, a gorgeous trio of parrots endemic to Fiji.

The Horned Parakeet (Eunymphicus cornutus) is a New Caledonian relative of the kakariki. Tunpin Ong (Creative Commons Share-alike)

The Horned Parakeet (Eunymphicus cornutus) is a New Caledonian relative of the kakariki. Tunpin Ong (Creative Commons Share-alike)

As you can see from the phylogeny, neither the Orange-fronted Parakeet nor the Chatham Parakeet belong with the Yellow-crowned Parakeet. Similarly, apart from the Chatham race of Red-crowned Parakeet, the other subspecies with red crowns are distinct, and can only be lumped with the Red-crowned Parakeet if every other kakariki is too. It seems that the red-crown is the ancestral phenotype, from which the yellow crown is a derived characteristic that evolved separately on three occasions (for the Orange-fronted, Yellow-crowned and Chatham Parakeet respectively). The study did not examine the extinct species of Lord Howe Island, the Society Islands or Macquarie Island (it did report findings on Macquarie but the specimen was later reported to be a misidentified Red-crown from the Antipodes).

If this were simply an exercise in scientific showing off this wouldn’t really matter very much. But it does matter. Consider the title of a 1981 article in the New Zealand ornithological journal Notornis, “The orange-fronted parakeet (Cyanoramphus malherbi) is a colour morph of the yellow-crowned parakeet (C. auriceps)“. As journal article titles go that is pretty forthright. Conservation budgets are tight, and why save a morph, even a distinctive one, when there are species that need help? Indeed, subspecies are themselves lower conservation priorities than species. The Grey Duck is expected to become extinct in New Zealand soon, but is not the subject of conservation efforts as it remains common elsewhere.

How you draw species limits has implications for assessing the situation of species, and the situation facing the Cyanoramphus parakeets is bad. As already noted two species have been lost, in addition populations (of uncertain taxonomic status) have been lost from three islands have been lost (Macquarie and Lord Howe were both encountered by European scientists, but the presence of the genus on Campbell Island was only recently discovered via fossils). The surviving species and populations have mostly all declined, underscoring the importance of knowing what constitutes a species. Under the splits proposed by Boon, the New Caledonian Parakeet is listed as vulnerable and the Chatham and Norfolk Parakeets are both endangered. The Reischek’s Parakeet (Cyanoramphus hochstetteri) isn’t treated as a separate species by the IUCN, the only split that isn’t, but if it were it would probably warrant a precautionary vulnerable status similar to the Antipodes Parakeet (the island is predator free but vulnerable to a freak event). Of the other three species the Orange-fronted Parakeet is critically endangered (but survived its brush with unimportance), the Red-crowned Parakeet is mostly restricted to offshore islands and considered vulnerable. The Yellow-crowned Parakeet is the only relatively secure species, still relatively common on mainland New Zealand and listed as near threatened.

Norfolk Parakeet juvenile (Cyanoramphus cookii) Paul Gear

Norfolk Parakeet juvenile (Cyanoramphus cookii) Paul Gear

Taxonomy is important, but not I should add, essential. A lot of the important recovery work on the Norfolk Parakeet, which was down to only 30 odd birds and around 4 females, was done prior to the split. But one source I have read described an increase in conservation efforts for the Chatham Parakeet once its specific status was established. Considerable efforts are also being made to save the Orange-fronted Parakeets after their population crashed from 700 to less than 200 between 1999 and 2000 (due to bad rat plagues caused by beech masting). Would such efforts have been made were it still considered a mere “morph” (as it was as late as 1998)?

This has gone on a little longer than I intended! So I’ll talk about the second problem surrounding the kakariki next week. In the meantime we can all reflect on the importance of taxonomy beyond giving us armchair ticks.

Great article, Duncan! This is a bunch of birds I have been entirely ignorant of up until now and I find this stuff fascinating. Looking forward to part (or problem) two.

They are a pretty neat group that are lucky to have had several good scientists take a look at.

New Zealand is the nightmare of any world twitcher (not that I am one): too many endemic island forms that are hard to see (with many islands being off-limits) and that frequently get elevated to species levels. Which means that it will take ages, numerous special permits and several trips to see all endemic species. And even if you’ve mastered that, you’ll have to return a couple’ years later because of all the splits that have occured in the meantime.

Not that I’d mind that… but then I am not a world birder.

This was a mean post: how will I be able to go on living, knowing there is a Horned Parakeet out there, a species I have never seen and am unlikely to ever see. Thanks for that, Duncan! 😉

It isn’t like I have seen it… yet. New Caledonia is top of my to-do list while I’m in New Zealand but the place is brutally expensive.

As for hard to see kiwi species, I think it would be hard to beat the Auckland Island Rail or the Chatham Snipe.

Or the Black Robin, or the Chatham Parakeet, or the Little Spotted Kiwi, or the Kakapo,… and even though Orange-fronted Parakeets are generally not off-limits, they are not exactly guaranteed during a short field excursion even within their range, right?

And the emotional side of the problem is that we are not talking about different Acrocephalus warblers that are only distinguished from each other by primary spacing or song. We are talking about some of the world’s most enigmatic and fascinating species.

* SIGH *

And New Caledonia isn’t only very far away from Europe, it is also brutally expensive??

* DOUBLE SIGH *

To be honest I think the Auckland Rail pretty much has most of them beat. There are ways and means of getting to see the Chatham species, or the Kakapo, revolving around volunteering for DOC. But Disappointment and Adams Islands, which are the only places you’ll see the Auckland Rail, I’m not aware of anyone going to them often at all.

And Little Spotted Kiwi are not hard to find.

And New Caledonia seems particularly expensive if you’re using Kiwi dollars. With pounds or Euros it probably seems fine.

Good job Duncan. Enjoy read ur blog seriously …. 🙂 birds come first

Just wondering if a date for the origin of the NZ red-crowned kakariki has been determined? According to the phylogenic tree on http://10000birds.com/regarding-kakariki.htm it is the same time as the Chatham Island red-crowned kakariki?